Cameos have existed since ancient Egypt and play an essential role in the history of jewelry. In materials such as onyx, agate, or mother-of-pearl, which contrast with the color of the gemstone backing, the cameo acted as a miniature canvas to present carved portraits of kings, emperors, or scenes from mythology. As the world of antiquity became the stuff of myth and legend, cameos often served as proof of a Renaissance gentleman’s Classical erudition. Wealthy Italian dukes or cardinals studied these venerable objects in their studiolo (private offices). They displayed their ancient finds to close friends to demonstrate their knowledge of the Greco-Roman world. Over time, these ancient cameos became highlights in the collections of Renaissance royals and scholars, Neoclassical aristocrats, and modern museums.

Yet despite the cameo’s ancient origins and its status as a classic jewelry item, the Black community has often had a complicated relationship with these pieces, especially due to a history of racist caricature in the imagery that also became associated with the cameo.

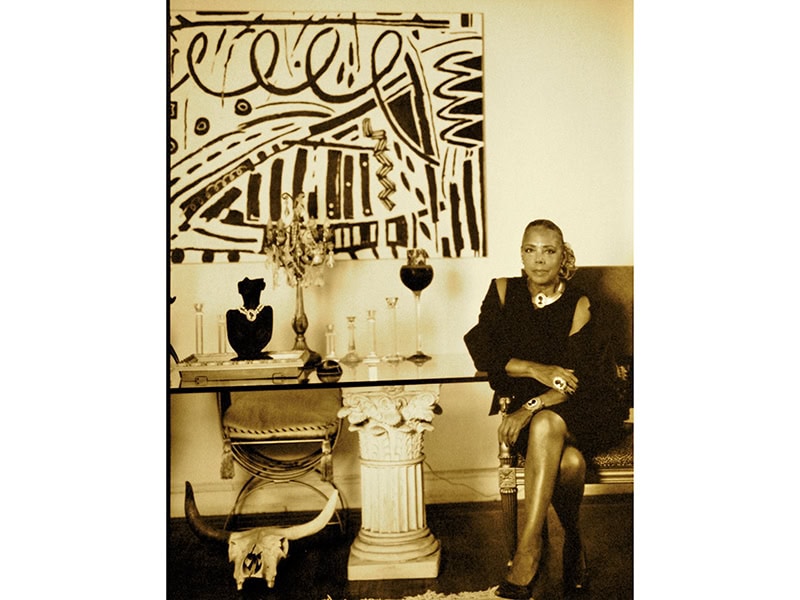

Artist Coreen Simpson wanted to explore this issue of representation by making her own American take on the cameo. In the 1990s, Simpson developed a cameo for modern Black consumers. In so doing, she built a successful company that subverted the negative historical narrative.

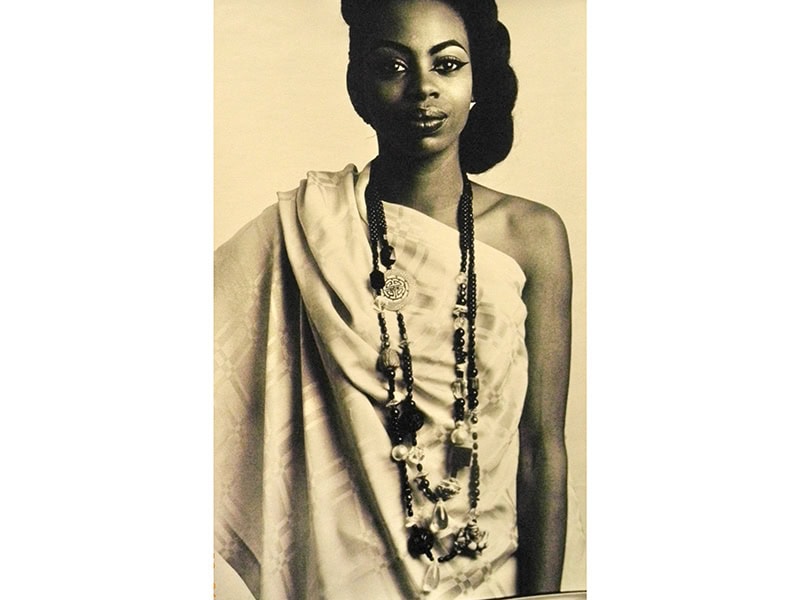

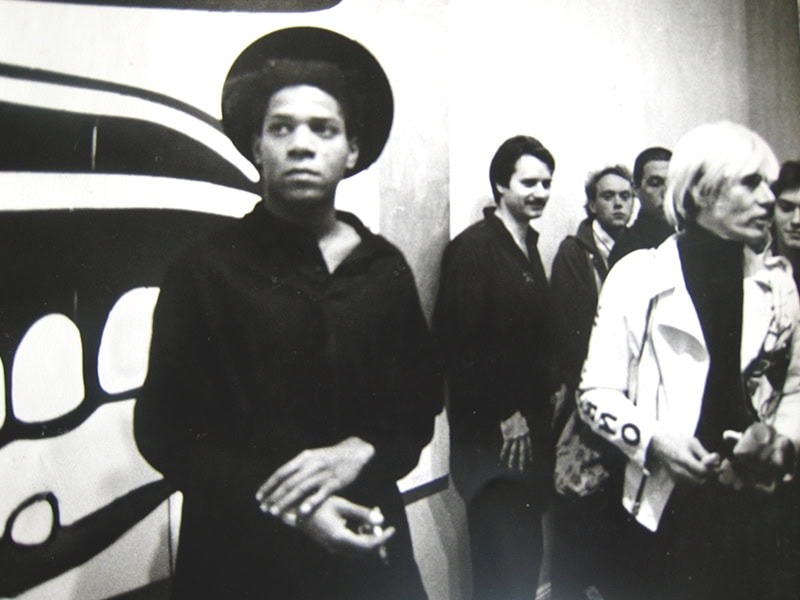

Originally, Simpson made a name for herself as a photographer documenting the art scene in 1980s Harlem, including the work of the Just Above Midtown (JAM) gallery that started the careers of many prominent Black artists of the late 80s, such as David Hammons and Lorraine O’Grady. But through her love of jewelry-making and her determination to give the cameo a place of respect for Black culture, Simpson built a business that has seen her cameos featured all over the world and on the lapels of some of Hollywood’s most important celebrities.

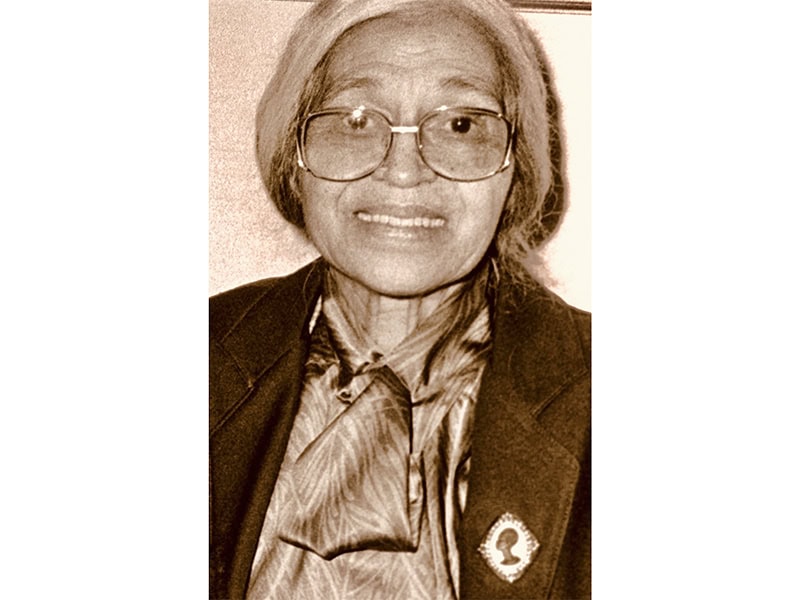

Coreen Simpson was born on February 18, 1942, in Manhattan, to a white mother and an African American father. After issues that involved child protective services, Simpson and her brother were removed from her biological family. First a childless couple in Long Island raised her, then the Davis family, in Brooklyn. Simpson recalls being born with a photographer’s eye of the world.

As a girl she sat on the stoop outside her Brooklyn brownstone and watched the fashionably dressed people walk by. She captured each image like a photo, “a blink of her eyes” acting as a corporeal camera shutter. Simpson remembers her biological father giving her a gold bracelet and ring as a young girl—her first meaningful encounter with jewelry. Although she lost them, the gift remains one of the memories she has of her father before they were separated.

Simpson completed her high school education at Samuel J. Tilden High School, in Brooklyn, in 1960. She didn’t go to college immediately after graduation. She wed in 1963 and started a family. After three years of a stormy marriage, Simpson separated from her husband. He disappeared, leaving Simpson as a single mother with two children.[2]

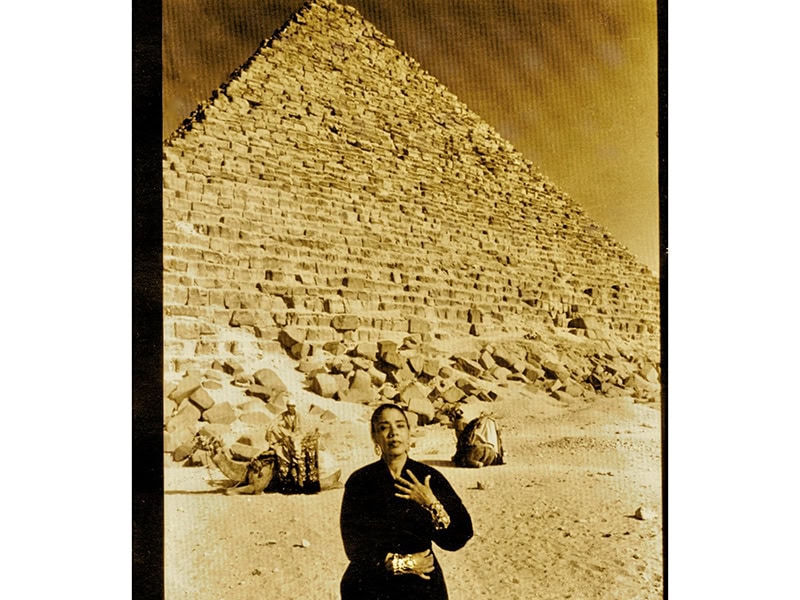

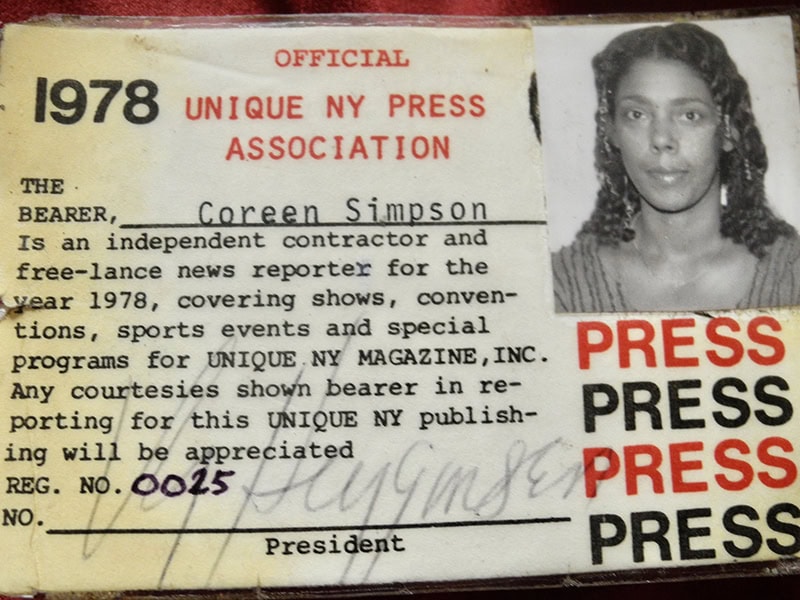

To survive that financial situation, she took day jobs as a personal secretary at various companies, including NBC and RCA. She also wrote lifestyle articles at night, after work.[3] She sent one of her articles, an autobiographical account of her experience as a Black woman visiting the Middle East, to Essence magazine. Although this article wasn’t published, it continued her drive to keep writing. She published in other small magazines and eventually became one of the editors of the magazine Unique New York (started by radio personality Vy Higginson) in 1980.

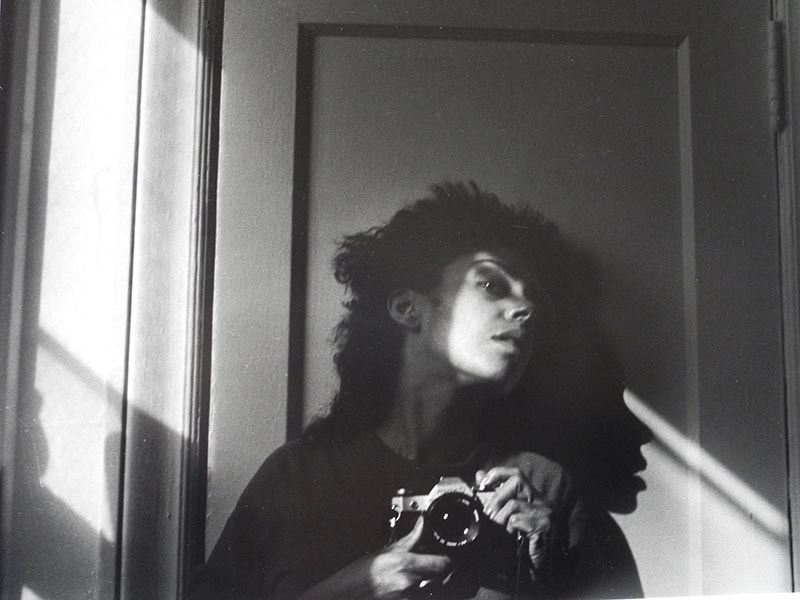

Simpson views these as her first steps into photojournalism, as she eventually moved into taking photographs to accompany her texts. During the completion of a writing assignment that required images, Simpson decided to take photos herself instead of enlisting an outside photographer who created low-quality work. She borrowed the camera of a friend, the photographer Walter Johnson, and learned the basics in 30 minutes. Simpson’s love for photography was born. “I figured if [people] liked the pictures, it would be a good article because it’s not a good article if the pictures suck,” Simpson stated in an interview. “The pictures need to say something.”[4] As the published photos increasingly got a positive response, she eventually made the decision to focus her career on photography. This chance path and self-reliance is a pattern often seen throughout her career.

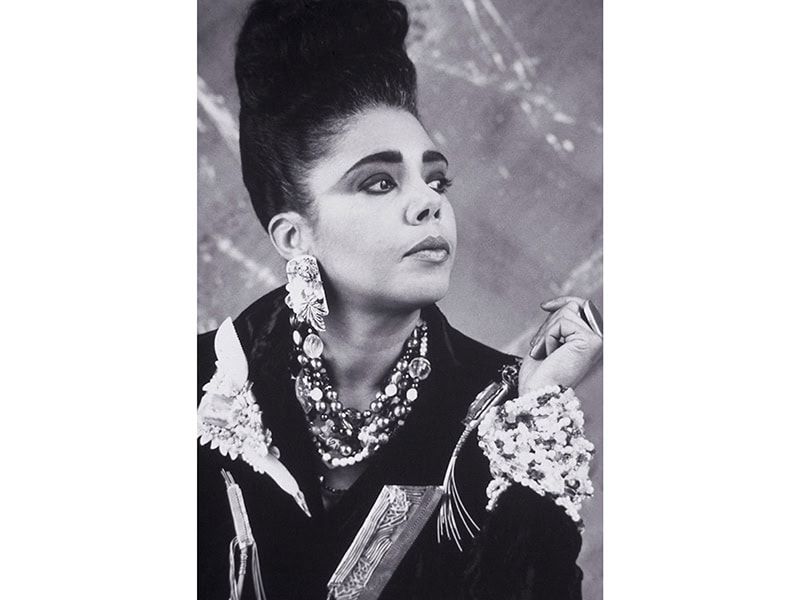

Simpson refined her skills throughout the late 70s. Her work attracted the interest of the curator Reginald McGhee, from Studio Museum in Harlem. He invited Simpson to become a curatorial assistant. In this position she met other renowned Black photographers.[5] She first learned additional techniques from her aforementioned friend, Walter Johnson, then studied how to develop film under Frank Stewart around 1977. She developed a style of candid street photography and portraiture influenced by Diane Arbus, Baron Adolph de Meyer, and Weegee, combining the spontaneity and structured planning of all three artists.[6]

Throughout the 1980s, Simpson’s photography became more well known, as she captured and documented New York in all its artistic diversity. Her images were often featured in Harlem-based newspapers such as the Amsterdam News, but also reached other papers citywide, including the New York Times, Essence, and the Village Voice, where she worked under photographer and editor Fred W. McDarrah, known for his photographs of the Stonewall riots and the Woodstock music festival.

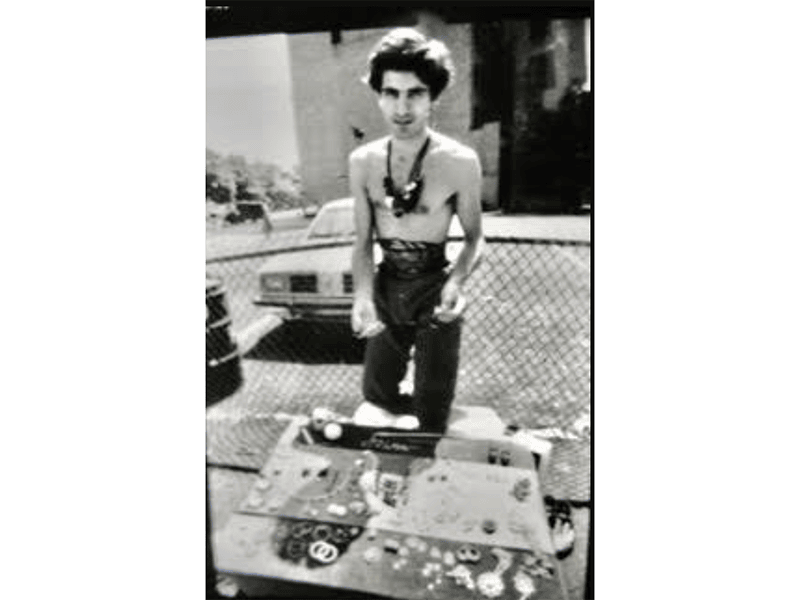

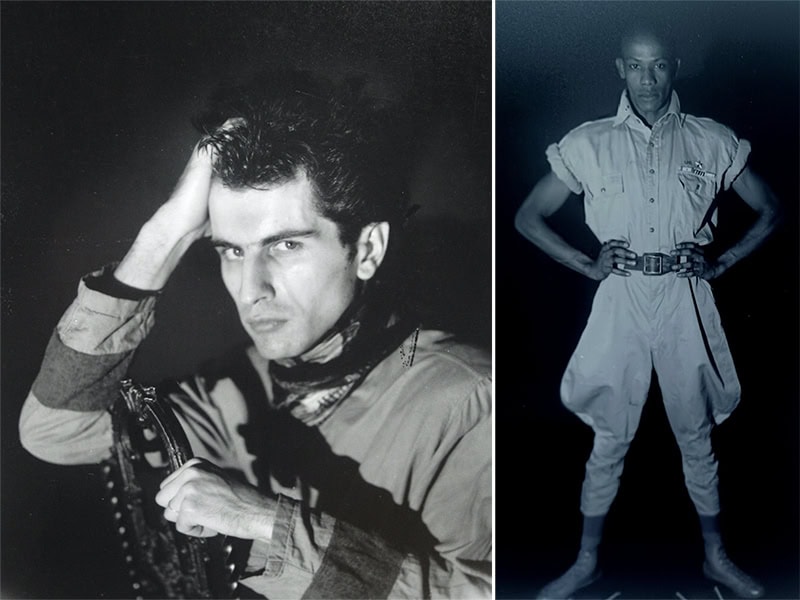

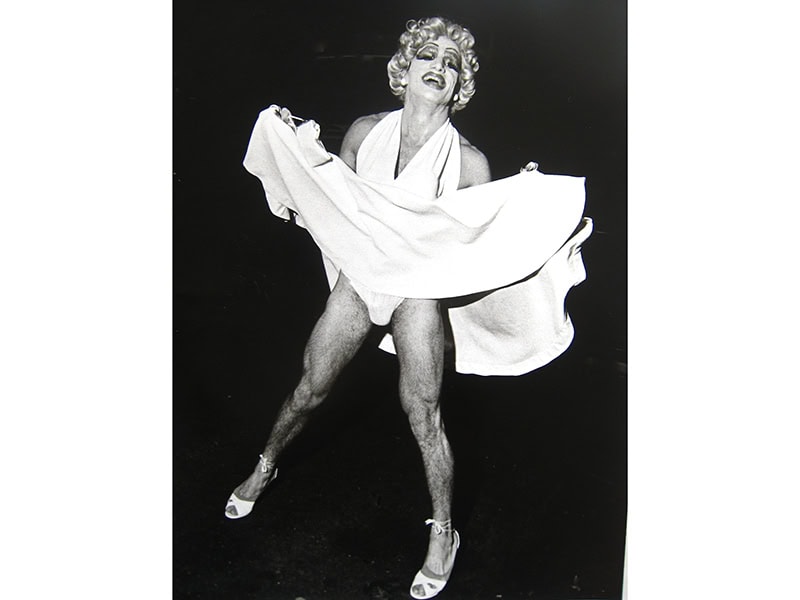

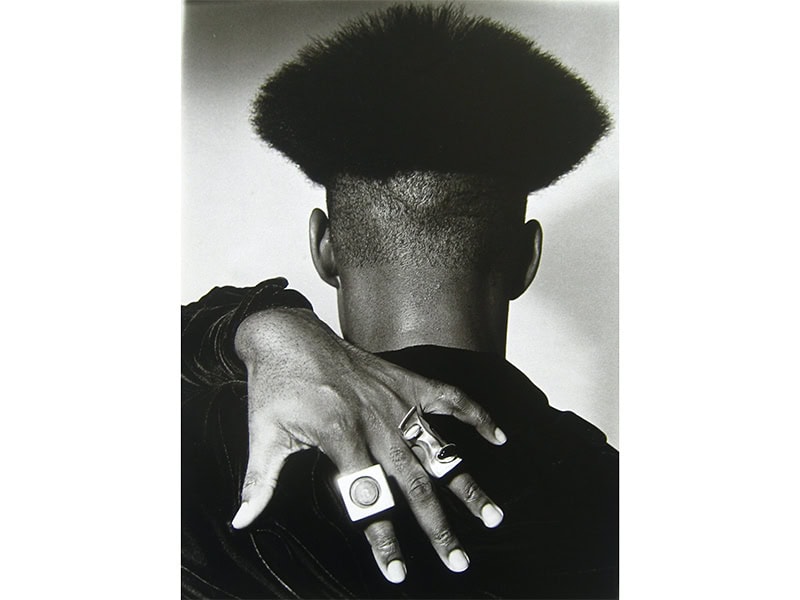

In an interview with Simpson, photography historian Rodger Birt described her images as capturing the outcasts of society—the transvestites,[7] the punks, and the hip-hop B-boys—with the intention of exposing “the dignity of her subjects, not just their vulnerability and alienation.”[8] In addition, her work captured important African American cultural events and nightlife in Harlem, and she documented the art scene of JAM gallery, recording important works of performance such as Lorraine O’Grady’s Mlle Bourgeoise Noire.[9]

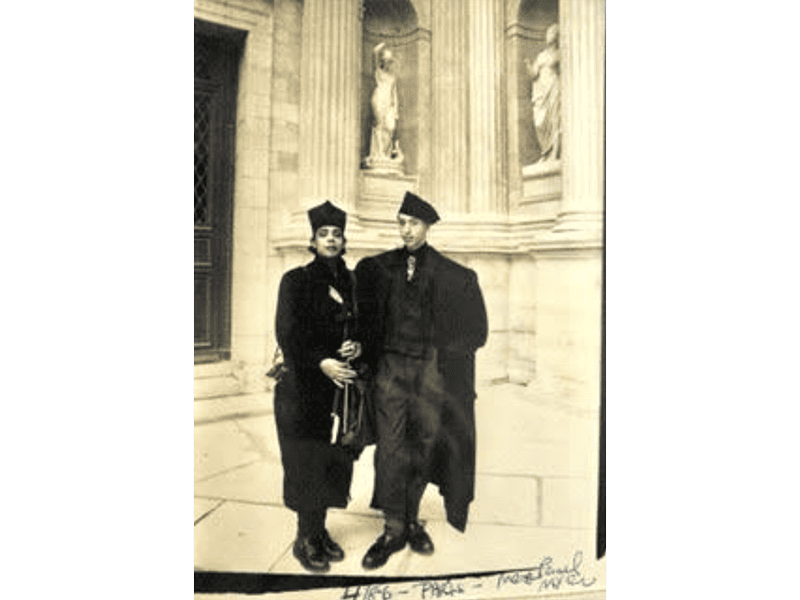

As her skills grew, Simpson added more famous faces to her portfolio, including Eartha Kitt, Jean-Michel Basquiat, David Bowie, and Nina Simone.[10] Simpson’s career also took her to Paris, where she became one of the few female photographers to regularly cover fashion shows. Fashion had already been a long-standing interest. In fact, in the 70s she had attended the Fashion Institute of Technology (FIT) to take night classes to study dress design, but difficulties arose and she did not complete the class after becoming disinterested by the required precision.[11]

Eventually, fashion magazines, including Vogue, published some of her photos. Others were later collected by major institutions around the world, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Smithsonian, The Bronx Museum, Belgium’s Musée de la Photographie, and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.[12]

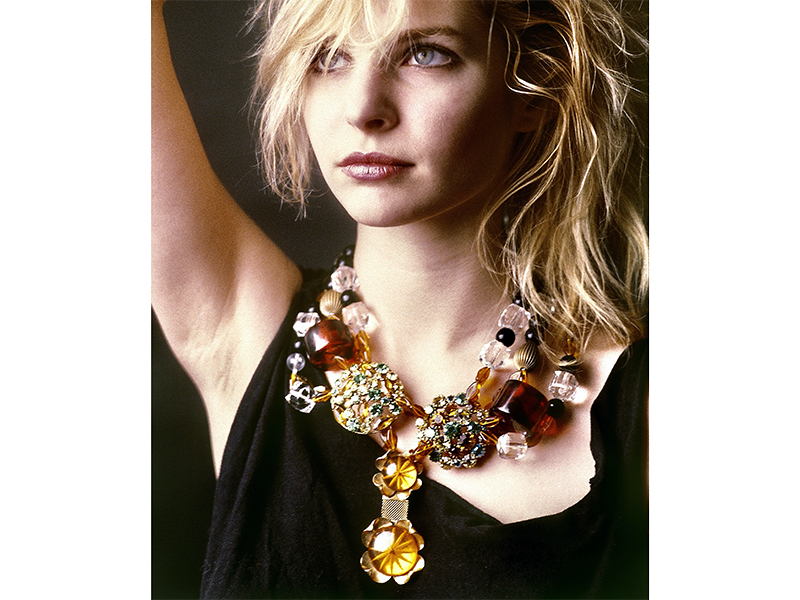

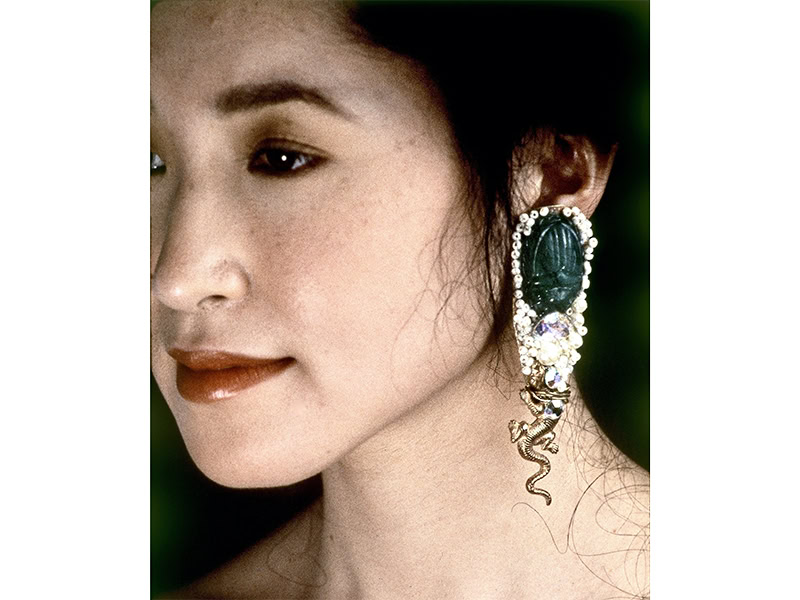

Simpson started to develop her skills in jewelry-making during this time. Her first foray into jewelry came as a product of necessity. When she tried to find the right pieces to accessorize her outfits in various stores in Paris, she was often disappointed. The jewelry just didn’t fit her aesthetic. Because of this lack of options, Simpson decided to create her own. She immediately began a hobby, experimenting with pieces that she would wear herself and feature on her clients in photographs.

Her jewelry quickly gained a following in 1982, while she was photographing prêt-a-porter collections in Paris for Amsterdam News. As she worked by the runway, people—from show attendees to fashion aficionados to Essence magazine editor Mikki Garth Taylor—noticed her style and jewelry and took interest, asking her where they could get their own pieces.[13] This gave Simpson the idea to turn her designs into a serious career, and she started working to transform her work in jewelry into a fully realized business.

Simpson honed her craft by studying jewelry design and metalsmithing at FIT and Parsons School of Design. She sold her jewelry to multiple shops in the Garment District as part of the hustle to make enough money to survive in New York.[14] Her close friend Richard DeGussi-Bogutski was an assistant to Vogue editor Diana Vreeland. He often encouraged her to sell her work on the street, and they would sometimes set up their wares together. They maintained a close friendship until his death from AIDS complications.

Simpson eventually opened a showroom in the Garment District, and she continued to experiment with “unique combinations of stones, metal, and unusual materials.”[15] Simpson got her big break in the late 80s when, one day, as she was selling necklaces on 57th Street and Madison Avenue, close to the Henri Bendel department store, designer Carolina Herrera noticed her work and purchased 11 necklaces, which she featured in her 1988 resort collection. The journalist Renee White has also commented that publications such as Vogue described Simpson’s pieces as power necklaces, thereby cementing her position in fashion jewelry.[16] The New York Times proclaimed her a “style maker.” Stars such as Diahann Carroll and Joan Collins were seen wearing her pieces publicly and privately.[17]

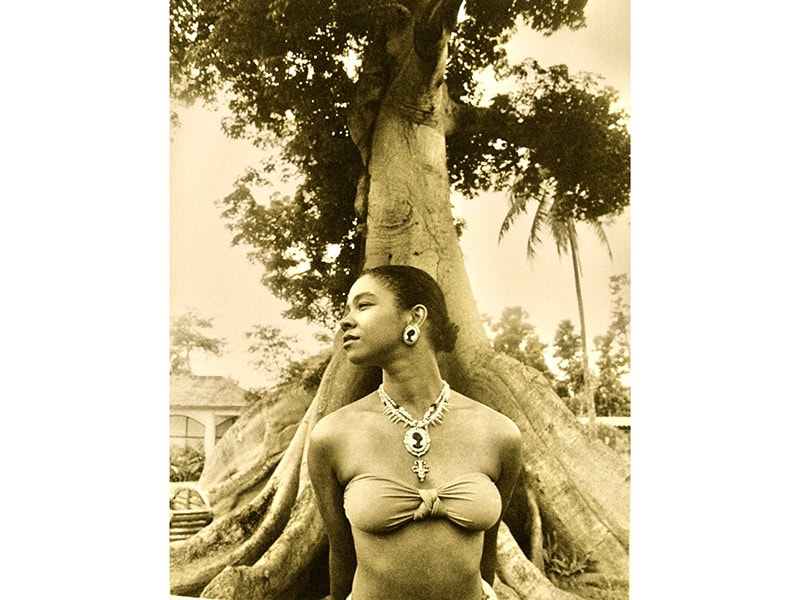

In 1990, all of Simpson’s experimentation in jewelry culminated in the launch of the Black Cameo, her signature collection. Her first encounters with the cameo had started as she paged through fashion magazines. She saw pieces she found beautiful, but she also thought “no Black woman [was] going to wear” them.[18] The cameos may have looked pretty, but they did not represent the cultural diversity of Black women in America.

Then, some of Simpson’s clients began asking for cameos featuring Black profiles, and Simpson wanted to fill their requests. She searched all over New York, from the Diamond District to the public library, but found no physical examples of cameos showing Black profiles, so she decided to make one of her own. But during her research, she had discovered the controversial history connected to cameos and the depictions often contained in them.

Starting in the 16th century, profiles of Black men and women were featured on Italian Cameo Habillé pieces (the figure in a Cameo Habillé wears jewelry with actual diamonds or gems in it) made using the blackamoor style. The subjects were styled as exotic bejeweled African princes and princesses. These pendants became popular as “racially coded signifiers of aristocratic identity” as they were traded among the European elite.[19] Although some of the cameos may have portrayed real African dignitaries, most portraits were created to bolster a European point of view that exoticized otherness of the African world. With the rise of the slave trade over the next few centuries, the blackamoor cameo, among other pieces of jewelry depicting Black subjects, more frequently depicted racist caricatures and stereotypes. Because of this dominance of false images, these adornments reinforced the removal of any agency and authenticity from Black people.

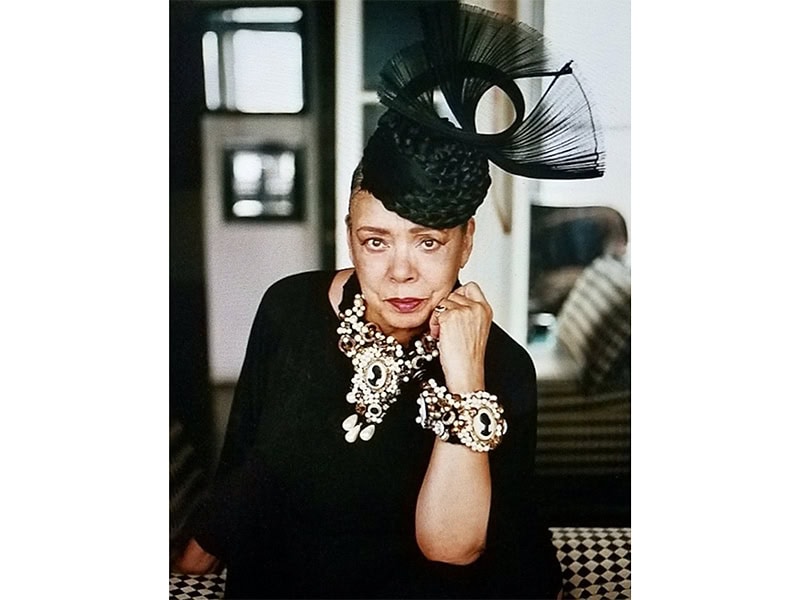

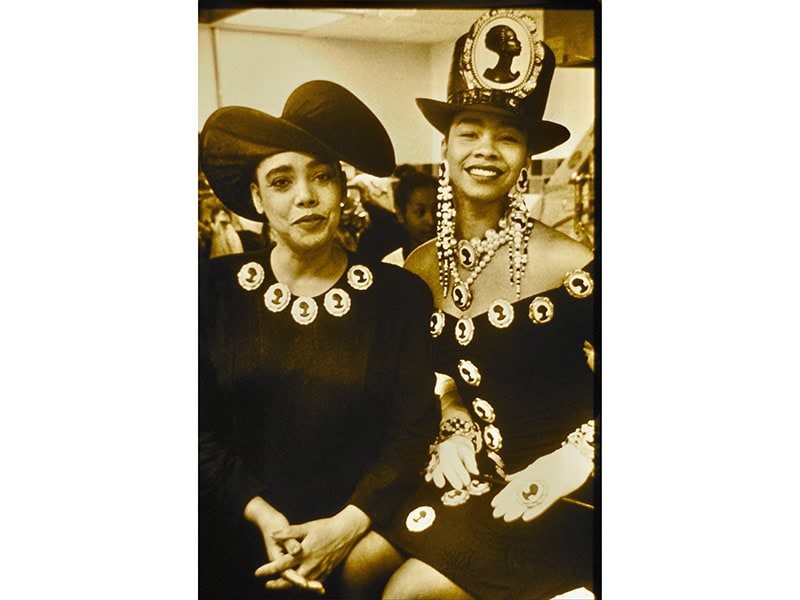

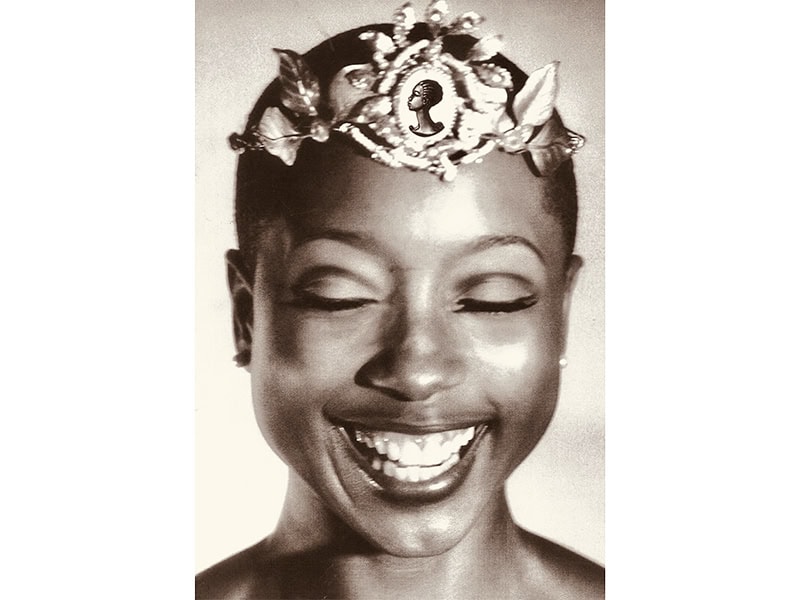

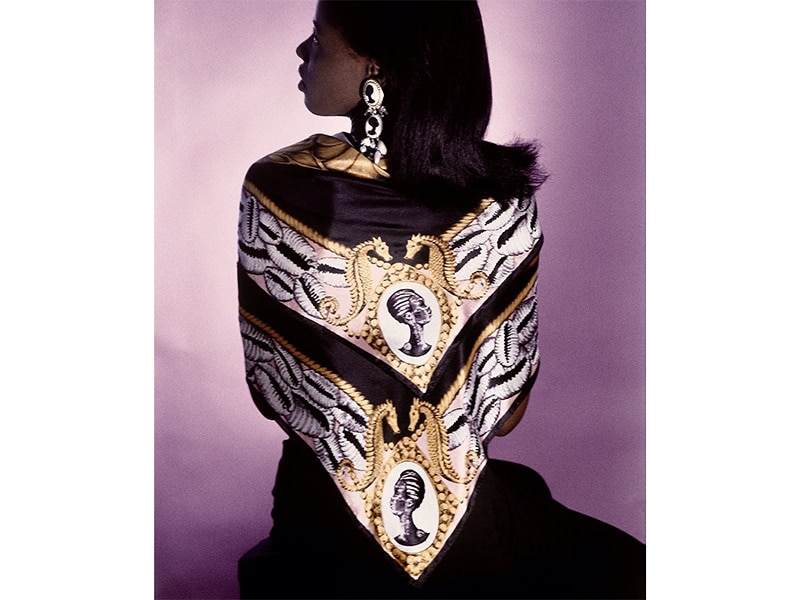

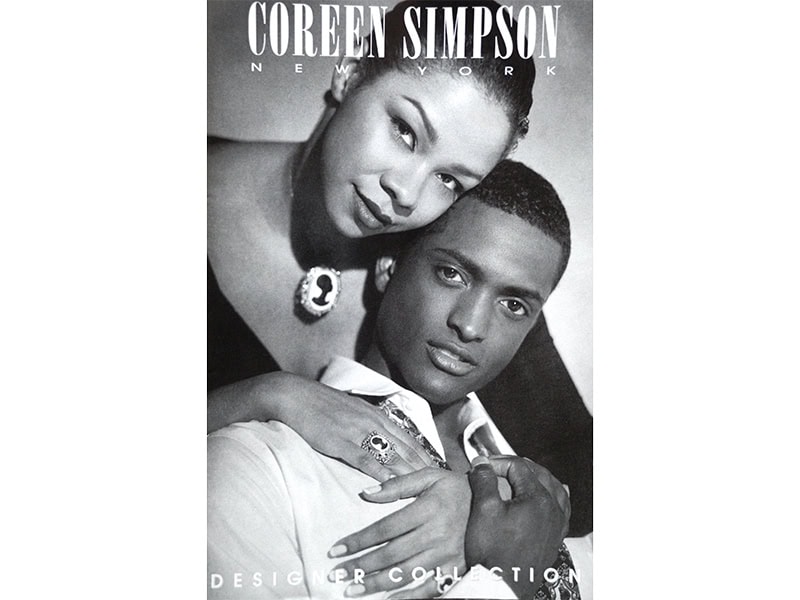

After learning this history of Black representation in cameos, Simpson decided to create her own. “My cameo is a modern take on the cameo for a Black woman in America,” Simpson said, “because I didn’t see any cameos [produced by a Black designer] made in America.”[20] She aimed to move the cameo away from a place of stereotype to a place of truth, one that finally “reflected the physical diversity of Black women.”[21] With this vision, and using white metal, Lucite, and slate, Simpson created brooches that were 2 x 2 ½ inches (51 x 64 mm) and featured different raised profiles of Black women to represent “the beauty of the African American woman for [1990].”[22] These portraits were placed against a white oval background and encased in a Baroque-style frame of gold-plated pewter. After the initial design process, Simpson collaborated with a Rhode Island jewelry company that mass-produced the pieces.[23] Simpson named these brooches the Black Cameo Collection and sold them for $120 at locations including the Studio Museum in Harlem—her former workplace—the Bronx Museum, and the One of a Kind Boutique, in Manhattan.[24]

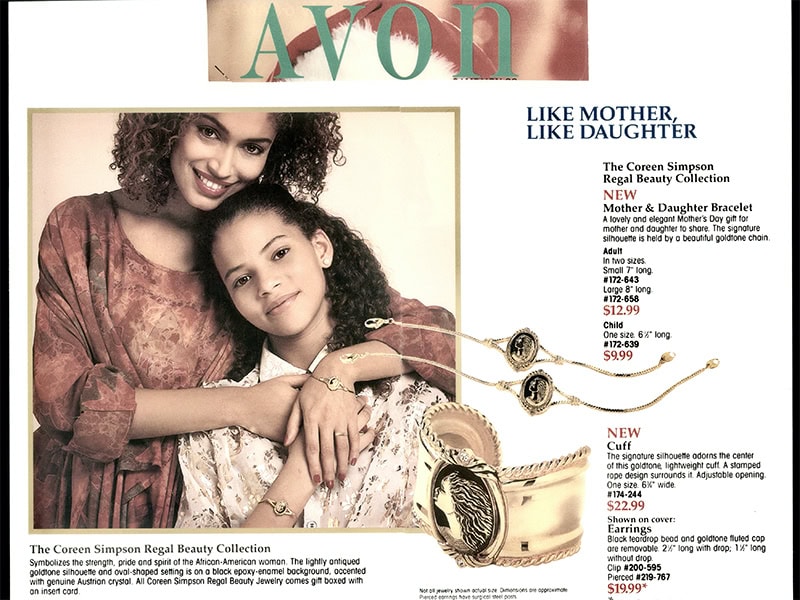

Press reviews gave the collection wide publicity. The brooches were a national hit when they first launched, with newspapers such as the Chicago Tribune describing her as “one of the most successful designers in the power-pin market.”[25] In 1994, the popularity of the Black Cameo attracted the interest of the then very well-known cosmetics company Avon,[26] and Simpson entered a licensing agreement with the corporation, launching a specialty limited-edition set called the Coreen Simpson Regal Beauty Collection.[27] Featuring brand-new cameo designs, the deal continued for three consecutive years, making the collection a big success.

Before long, Simpson’s cameo business expanded into necklaces, earrings, cufflinks, and many other pieces of jewelry designed in her Black Cameo style. Soon many celebrities sported a Black Cameo, from actress and model Toukie Smith[28] to Cosby Show actress Phylicia Rashad, from Illinois Senator Carol Moseley Braun to TV personality and entrepreneur Oprah Winfrey,[29] and from the entertainer Debbie Allen to the late jazz singer.[30] Thirty years later, the Black Cameo is still an important collector’s item, and even current artists such as Rihanna can still be seen wearing a Black Cameo to events.

Simpson’s successes in jewelry design and business have garnered her many accolades among institutions, including an official honor from the Smithsonian Institution for outstanding contribution to design, in 1992; the Entrepreneur Award from the National Association of Market Developers; the Madam C. J. Walker Award for outstanding economic development, presented at Columbia University in 2000; and many others.[31] Simpson’s work in both jewelry and photography continues to be exhibited in important institutions, including a recent MoMA exhibit exploring the lasting legacy of JAM Gallery.

Simpson’s work is primarily defined by a persistence to make sure her work fits her vision while also remaining comfortable for the customer. “When I’m making pieces, the first piece I make is what I would want to wear,” Simpson says, emphasizing the importance of bringing her own integrity to her designs.[32] Yet while letting her voice speak out in a piece, she heeds her clients’ needs, too. She stated, “I think [a piece] is about other people. … your customers tell you what they want … [but] not everybody can wear my aesthetic. … any designer has to listen if they want to make [a piece].”[33]

The DIY approach spans Simpson’s entire career. When she couldn’t find a photographer who fit her aesthetic, she learned to snap shots and later developed her own photographic style, one that captured the best of Black New York in the 80s. When she couldn’t find jewelry to accessorize her bold fashions, she created her own. Finally, when she couldn’t find a cameo that properly depicted the modern Black woman, she created her signature piece, designing cameos with imagery that portrayed the diverse beauty of Black women around the world.

Coreen Simpson carved a place in the world of jewelry for Black representation in adornment, and in the process created an iconic cameo. By depicting Black men and women in a space formerly reserved for gods and kings, she proves how historic pieces and traditional forms, even the ones dating to the beginnings of human civilization, can still be innovative and important to us today.

RELATED

Black Jewelers: A History Revealed—Curtis Tann: Almost Lost to Time

Black Jewelers: A History Revealed—Bill Smith

[1] Coreen Simpson in an interview with the author, July 13, 2023.

[2] Coreen Simpson in an interview with the author, August 31, 2023.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Rodger Birt, “Coreen Simpson: An Interpretation,” Black American Literature Forum 21, no. 3 (1987): 290.

[7] This outdated term is what people who dressed outside of traditional gender norms were then called.

[8] Birt, “Coreen Simpson,” 290.

[9] Simpson, interview August 31, 2023.

[10] Ron Scott, “Simpson and Stewart, No Smiles for Miles, Chet Baker,” New York Amsterdam News (New York), May 2016: 25.

[11] Birt, “Coreen Simpson,” 289–304.

[12] Salah M. Hassan, “’1 + 1 = 3’ Joining Forces: Coreen Simpson’s Photographic Suite,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art 30 (Spring 2012): 44–59.

[13] Renee M. White, “A Look at ‘The Black Cameo’ Book,” New York Amsterdam News, April 2009: 16.

[14] Simpson, interview August 31, 2023.

[15] White, “A Look.”

[16] Ibid.

[17] Alison France, “Style Makers; Coreen Simpson, Cameo Designer,” New York Times, Late Edition, February 25, 1990.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Kim F. Hall, “’An Object in the Midst of Other Objects’: Race, Gender, Material Culture,” Things of Darkness: Economies of Race and Gender in Early Modern England (Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press, 1995), 213.

[20] Simpson, interview August 31, 2023.

[21] France, “Style Makers.”

[22] Renee Minus White, “Coreen Simpson, Top Photog. Creates Spring ‘Black Cameo,’” New York Amsterdam News, Jan. 20, 1990: 17.

[23] Simpson, interview August 31, 2023.

[24] France, “Style Makers.”

[25] “Pin Power,” Chicago Tribune, May 3, 1992.

[26] Avon is the second largest multi-level marketing enterprise in the world. Its products are sold by “Avon ladies,” who are contracted as self-employed sales representatives. They distribute brochures to advertise its products and make direct sales. Beth Kowitt, “Avon: The Rise and Fall of a Beauty Icon,” in Fortune 165, no. 6 (April 30, 2012): 106–114.

[27] Coreen Simpson, “History of the Black Cameo®,” The Black Cameo® Collection, https://www.theblackcameocollection.com/theblackcameo.html.

[28] Roy H. Campbell, “A Black Brooch Casts Cameos in a New Role,” Philadelphia Inquirer, May 20, 1990.

[29] Marisol Bello, “Designer Pins Pride on Black Cameo Collection,” Dayton Daily News, Feb. 6, 1994.

[30] Simpson, “History of the Black Cameo.”

[31] Ibid.

[32] Simpson, interview, August 31, 2023.

[33] Ibid.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and we will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org