It is another frequently unacknowledged fact that during the late Medieval and early Renaissance periods tapestries were valued as much as paintings—and in certain parts of Europe, even more so. Outside of Italy, tapestries solidified dynasties in a way that paintings could not. The nobility throughout Europe and England commissioned tapestries just as the Medici and the Vatican commissioned paintings and sculptures. But a strong association of tapestries with craft (and its accompanying themes of the feminine and domestic), occurring alongside the rise of the Renaissance myth of the inspired individual artist, eventually relegated tapestries to a subsidiary art form behind painting, sculpture, and even music.

For instance, LOOP XXIV is a relatively airy piece that combines three longer, almost horizontal strips with two sagging circles at one end. The feeling is of a coil becoming gently undone and sliding to the right (while still circling back on itself, as all of the brooches do). LOOP XXXIX, however, is a tight cluster of spirals piled horizontally on themselves. The opening at the bottom of the brooch serves less as an exit from this knotty entanglement and more like a support for it. Given that the “Loop Series” began in 2004 and is still ongoing, the wide range of shapes—and their corresponding set of ideas and emotions—is not surprising. Sometimes a temporary balance of sorts is achieved, as in LOOP XXXV, which beautifully combines vertical and horizontal shifts with a sense of both compression and spaciousness, or LOOP XXXI with its almost whimsical feeling of lift at the top. It is not a coincidence that these brooches might be worn near the heart.

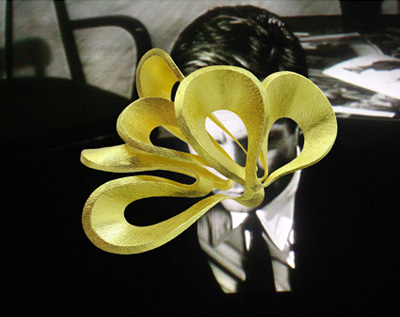

The “Loop Series” dynamics play out in gold, silver, and a darkened finish of oxidized silver that hints at Richard Serra’s monumental sculptural steel torques and ellipses that similarly emphasize movement within restraint. Gold, of course, signals most overtly that the brooches are jewelry, and in this sense pushes the work more toward being perceived as a commoditized object. Harder than gold, and less lustrous, silver emphasizes the line, and shows just how much Bürgel is drawing in and with the metals he uses to make these braided figures. In fact, each brooch in the “Loop Series” begins with an automatic drawing—quick, unpremeditated, with its echoes of Surrealist methods—which Bürgel scans into a computer and compresses before using the resulting image to cut out thin strips of metal he then begins to shape.

A sculptural component enters the process as Bürgel adds layers of metal, rounding and blunting the edges of each loop so that they, too, become another set of surfaces and lines. In a project related to the “Loop Series,” Bürgel made a large-scale wall relief with curved tubes of Styrofoam in 2006 for Goucher College’s Rosenberg Gallery. Yet even in his sculptural forays, the line remains primary, making Bürgel as much a draughtsperson as a jewelry designer,to which the close to eighty drawings on display at Gallery Loupe clearly attest. Line is both a measure and a freedom of the hand; it divides up and orders space while simultaneously introducing an element of uncertainty, the potential to veer off course. In mathematics, the line points to infinity even when less than the width of a page.

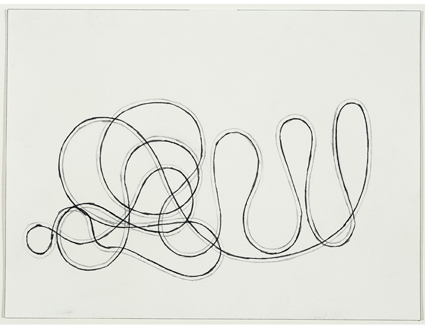

This untitled series of drawings began a year or more before the brooches, although they never serve as preliminary sketches for the jewelry. Instead, the two inform each other across media, with the drawings telling the mute brooches’ story, and the brooches partially operating as solidified line drawings. Formally, the drawings’ two mirroring lines—the lighter one appearing to shadow the darker one—reflect the brooches’ three-dimensional quality. Both the drawings and brooches appear quite smooth from a distance, yet their surfaces become more complicated when viewed from closer up. Both the drawings and brooches alternate expansion with an inward collapsing. They wriggle along a continuous line that appears to have no start or finish, and like Jacques Lacan’s Moebius strip they present an optical and conceptual quandary that makes it difficult to distinguish inside from outside, as well as clean demarcations between subject and object, self and other, private and public.

Along with sculpture, drawing, and jewelry design, yet another artistic practice has informed the work on display at Gallery Loupe—poetry. Specifically, Bürgel cites Rainer Maria Rilke’s “The panther” as capturing the spirit of the drawings in particular. In this poem, a panther Rilke watched in the Jardin des plantes sullenly stalks its cage. As translated by Edward Snow in NEW POEMS, the lines, “The supple pace of powerful soft strides, / turning in the very smallest circle,” capture the play of forces at work in Bürgel’s framed drawings, which similarly prowl around within a single sheet of paper’s relatively restrictive parameters. Here, the space between the lines is as important as the line itself. Despite its entrapment, the panther’s pacing is “a dance

of strength” in Rilke’s poem; similarly, the line in Bürgel’s drawings shows a supple firmness and discontented energy.

If the Renaissance created a temporary wedge between art and craft, there have also been plenty of moments in art history that sought to fuse them back together: Renaissance- era cabinets of curiosity, William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement, the German Bauhaus, Etsy. Bürgel’s “Loop Series” brooches bring craft to the realm of fine art, venture into the sculptural, and initiate a dialogue with the series of line drawings that both elucidate the brooches and exist as accomplished works on their own. while formally enchanting, the brooches and drawings strain toward the limits of form, motioning to a larger narrative that the wearer and viewer must help supply. whatever uncertainties may arise are compensated for by the urgency of Bürgel’s com- pulsive searching within and across different artistic media.

(Rainer Maria Rilke. “The Panther.” In New Poems: A Revised Bilingual Edition. Translated by Edward Snow. New York: North Point Press, 2001. 63.)

Alan Gilbert is the author of the poetry book, Late in the Antenna Fields (Futurepoem), and a collection of essays, articles, and reviews entitled Another Future: Poetry and Art in a Postmodern Twilight (Wesleyan University Press). His poems have appeared in BOMB, Boston Review, Chicago Review, Denver Quarterly, Fence, jubilat, and The Nation, among other places. His writings on art and poetry have appeared in a variety of publications, including Artforum,

The Believer, Bookforum, Cabinet, Modern Painters, Parkett, and

The Village Voice. He lives in Brooklyn.

Note from the editor: This is my last week as editor of the AJF blog. It has been a great pleasure working together and I want to thank all the writers, artists and colleagues who have made the blog such a success. Thanks. Mike Holmes