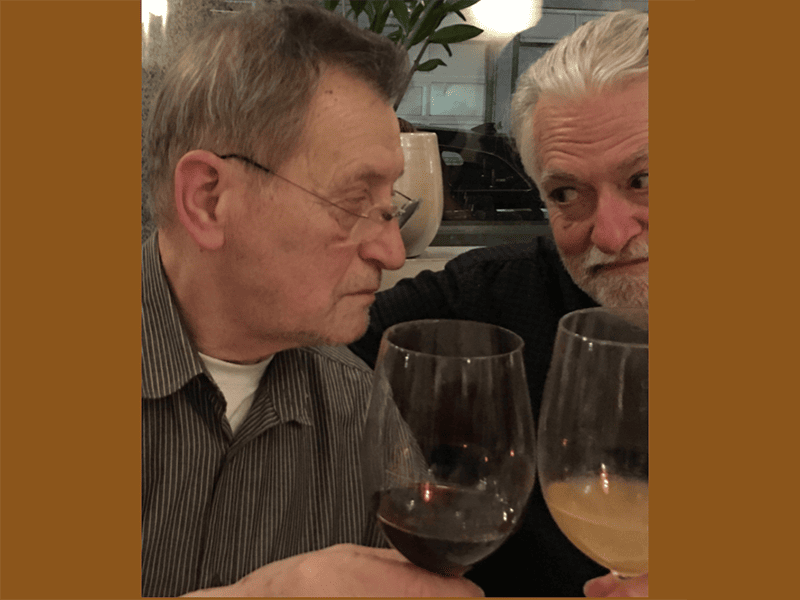

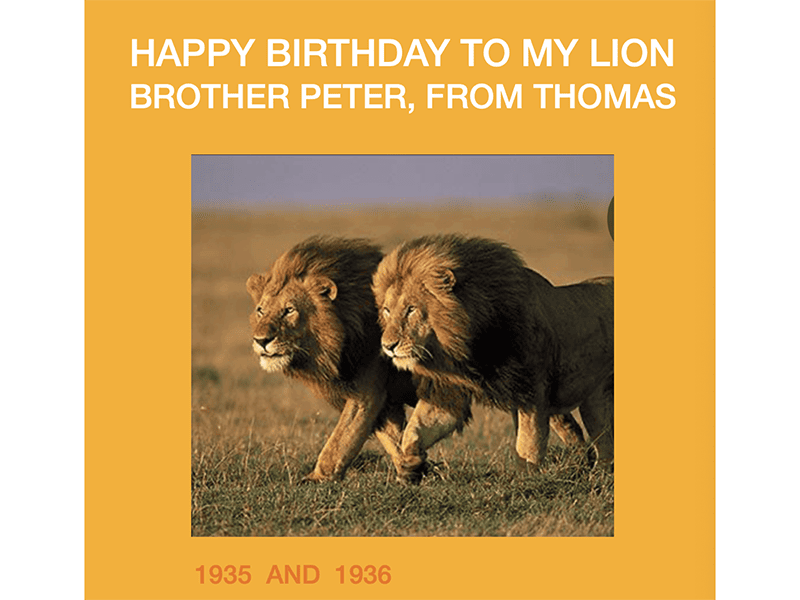

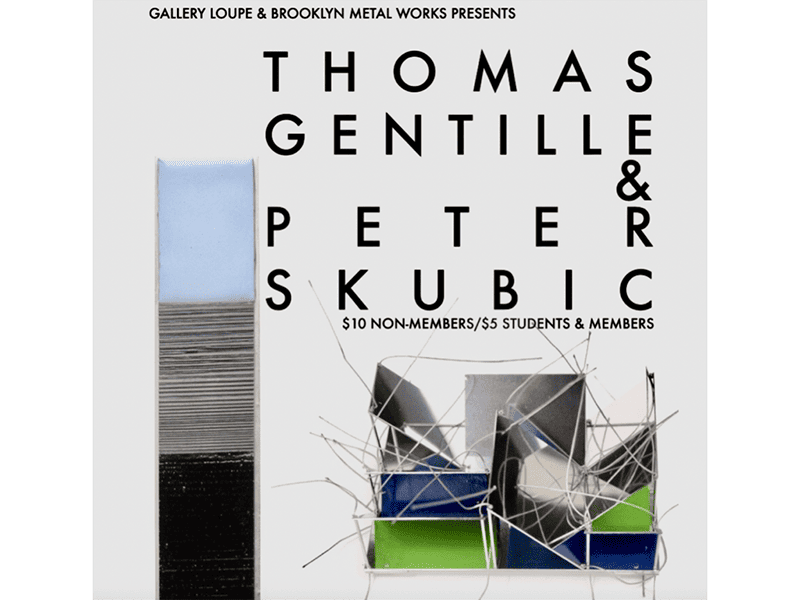

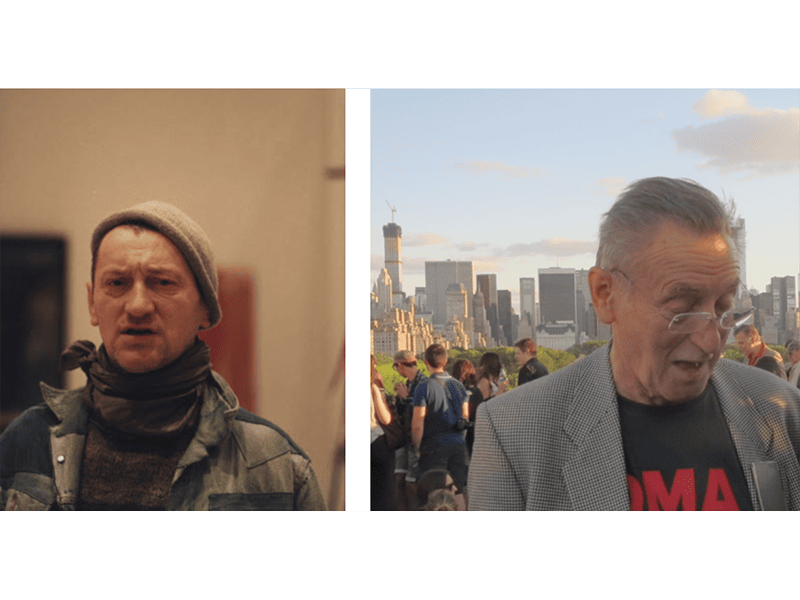

Peter Skubic, the great jeweler/sculptor, had a fine, large, high-ceilinged apartment in Vienna, as well as a farmhouse in the village of Gamischdorf, Austria. Peter and I were born on the same day, August 11. Peter was one year older than I. Astrologically speaking, we are Leos. Partly because of this coincidence of nature, the fact is we have both devoted ourselves to making jewelry in totally non-objective ways. Similar theories and sensitivities run through our veins, touching at points. Beyond this, our work is entirely different. I have great respect for Peter’s work, and I believe it was reciprocal. It is through these vehicles that we became friends. But it may not be for those reasons at all. It may be that we just liked one another.

He invited me to see his house and studio in St. Michael. We were driving there from Vienna, Peter behind the wheel. The village is not very far from the Hungarian border. I asked Peter if we could cross into Hungary for just a few minutes. It was 30 or so kilometers out of our way, but Peter said, sure, why not, “I know a place just over the border where we could get a late lunch.” The town, whose name I cannot recall, was in a sad state. Being forced to be part of the Communist regime had taken its toll. The buildings we drove by, in the downtown section, were universally a dismal dirty gray, in need of extensive restoration and repair. Now free from that oppression, the town was slowly improving. So far two shops we drove by had their facades newly remodeled. One small two-story building is memorable for its entire facade covered in geometric three-dimensional ceramic tiles glazed in an intense shine of brilliant orange. They threw a radiant glow, in a burst of the new freedom, subsuming the gloom of adjoining buildings.

At the edge of town stood an isolated tavern, a rather rough truck stop and local bar, morphing into a more sedate restaurant for the locals in the evening. I’m a red meat vegetarian, which is to say I eat fish and fowl, none of which were available. Peter had a fine big lunch, a goulash. I settled for an authentic Hungarian Crepes Palacsinta, which was one of my reasons for wanting to go into Hungary. The only available filling was unsweetened apple sauce, with apple juice as a beverage. It was half diluted with water and sadly tasteless. But all was followed by two refreshingly good cups of tea. Peter said not to worry, we would be home soon and he would make me a noodle soup from chicken broth. He had great loaves of bread, and some good cheeses as well, and would make us espressos.

There was a problem. The border crossing we had come through allowed Austrians and Americans entrance into Hungary. Through special diplomatic arrangements, Austrian passport holders could go back into Austria through the same checkpoint. Americans could not. Consequently, Peter had to drive hours out of the way, literally through the dark of night on moonless, unlit back roads. By the time we got to Peter’s house, hours had passed. The car had heat, but beyond the windows it was March and bitterly cold. I was ravenous, and Peter was getting hungry again. He had a small black iron stove, very modern, in rectangular form. It used wood very efficiently for fuel and was used for both heating and cooking. Peter went back into the freezing night to chop kindling. Before long there was warmth, and a marvelous nourishing hot soup.

Peter had befriended a semi-feral cat that he called Katze, German for cat. When addressing the cat, he pronounced Katze in an endearing sort of way. Peter’s farm faces the village’s main street, Gamischdorf. When the garage’s wooden double-doors on hinges are opened, a courtyard is revealed. Katze was sitting there, brightly lit in the glow of headlights. Peter said he was always there waiting for him. Katze must have recognized the sound of Peter’s car’s motor as it approached. I was formally introduced to Katze, who followed us into the house, then disappeared. Peter said he had never come to anyone but himself, and so when Katze returned for his dinner I ignored him. Having owned my own cat, ’Zookie—short for Bazooka—when I was a teenager, I knew the best way to make friends with a cat who ignores you is to ignore them, and never let them catch you even glancing at them. Peter could not believe it when Katze, who had patiently waited for us to finish our soup—Katze’s dinner had been served before ours—jumped up and sat on my lap. I totally ignored him. He jumped down after a while, then returned three times. The third time I reached out and petted him. That was that. He jumped down, never to return. Katze had caught my attention. I had lost my edge of superiority. I was now considered riffraff, but the honor Katze had bestowed to me was a further bond between the Lion Brothers.

Peter laughed when I told him it was the best soup I had ever eaten. He said I was so hungry that anything I had would taste great. Maybe, but in my memory I can still taste the miraculous soup Peter had made. After dinner, Peter gave me two small plastic bags, each filled with stones. One held small dark red garnets that he had picked up on the floor of a garnet mine in the Czech Republic, in which the guide had said that anything the visitors could gather from the floor they could keep. The other bag contained some very small pebbles picked up on a beach in Europe. He said, “I thought you would like these, and maybe do something with them.”

The next day he drove us back to Vienna, where I caught a plane back to the States.

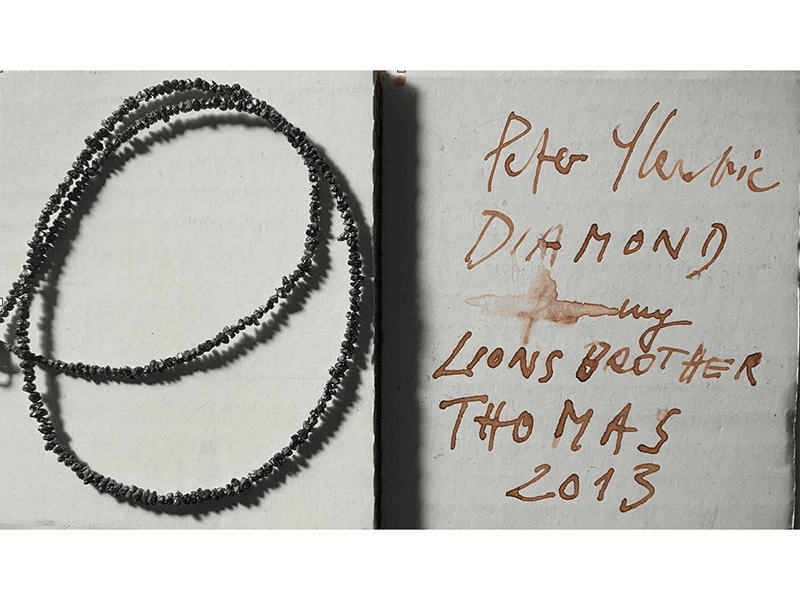

Some years later, Peter sent me a small necklace of tiny black diamonds with a note that said, “You can wear these or maybe use them.” I wear them occasionally. They scratch slightly, in a not unpleasant way, making their presence known. I wait for the right moment, and vehicle, to use them for Skubic Stones # III.

In another year in Vienna, Peter and I were walking through narrow cobbled streets on our way to somewhere I can’t now recall. A walk with Peter became quite an adventure, for he would stop at every shop window where there was even the slightest glimmer of jewelry. Whereas I can easily pass up almost anything that’s not contemporary artist jewelry, not Peter. You couldn’t drag him away from a window with any kind of jewelry—antique, commercial, platinum and diamonds, junk jewelry, ethnic, you name it. Then Peter, while standing there looking through gleaming plate-glass windows at brightly illuminated displays, would discuss every piece. I tell you, his critique was extremely instructive. It got so that I could hardly wait until we arrived at the next window. We were late when we got to where we were going. Peter had enthralled me, and himself too, at a dozen or so windows.

The back of Peter’s house on Gamischdorf slopes gently downward. It is filled with an orchard of ancient apple trees. In the fall, Peter gathered the ripened apples. On an antique apple press, he made cider, which he bottled in glass. The bottles, dark green, elegant, were like those used for Champagne.

In the Vienna apartment, Peter made crepes, dozens and dozens of them, warm-off-the-stove delicious, while Petra Zimmermann brought them out, one batch at a time, to serve six of us. Then Peter came from the kitchen, serving himself last and bringing out the Champagne bottles. Someone recognized them for what they were and said, “Ah, homemade cider,” and Peter replied, “No, no, it’s Thomas Wine.” Peter knew I was allergic to alcohol and had named it after me. Without fail, whenever I was around, he would declare it “Thomas Wine.” Peter’s kindness and consideration extended to everyone.

His pleasure and determination to always be making jewelry was evident, especially in St. Michael, where I spotted a window set deep within thick walls. The extremely wide windowsill was used as a jewelry bench. The light arriving through the window, and the view beyond, made it a very beautiful workplace. Peter stood there to work, for Peter, at one point, had injured himself. and was not permitted, until he was healed, to sit for long periods. (A muscle in his back, I think). When the windowsill became too crowded, he built himself an exceptionally tall jewelry bench of wood. There he would work, standing, for many hours at a time. It was long before I knew him, but the bench remained in its tall, regal proportions in case it be needed again.

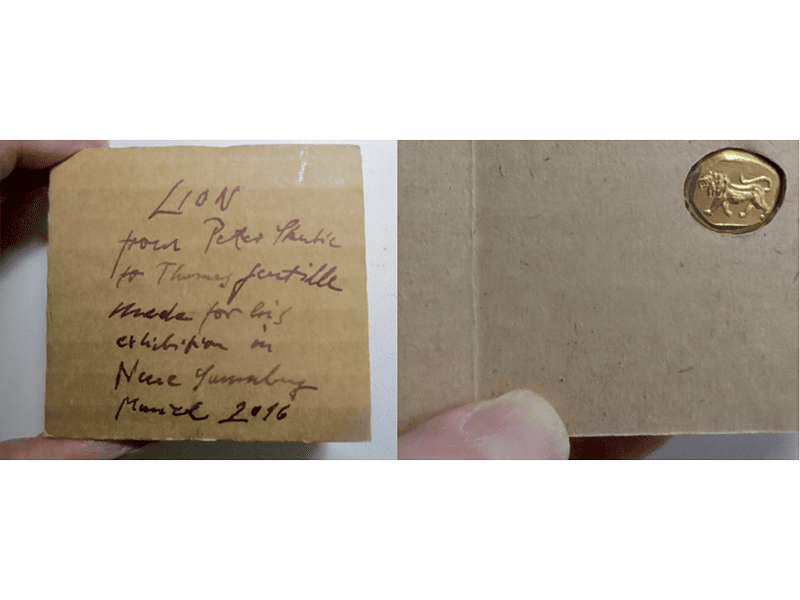

Peter and I exchanged Lion Brother gifts for many of those August 11 birthdays, though we were never together except in spirit.

There was some confusion as to how his last name is correctly pronounced. There were several of us together when the question came up yet again. Everyone hazarded their version of Skubic. After hearing them he said, “Whichever one you want, they’re all correct.”

When the death of my Lion Brother came, I, like everyone who knew him, went into deep grief. As fate would have it, I was playing a piece of music. I played that music over and over and over for three days running. The power of music helped me to accept this anguish, to hold it in check.

After those days I made this short video to honor Peter, my Lion Brother. The music is written by Fritz Kreisler and performed by Isaac Stern. Its title, “Liebesleid,” translates to “Heartache” in English. This is for Peter:

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org