On June 27, 2018, Marianne Unger-de Boer passed away at home in Bussum, the Netherlands, after a rich, yet too-short life. Marjan was 72 years old. As she liked to remind her audiences in lectures, she was born in February 1946, exactly nine months after the liberation of the Netherlands in May 1945. People who knew her will immediately recall her voice, way of speaking, and grinning laugh when she related this fact. Most people today will know her as “the” jewelry specialist, but she was much more than that. In fact, she engaged with the full breadth of design and likewise worked in all design sectors.

Marjan, born in a middle class family of entrepreneurs, started her life in the arts at the Kunstnijverheidsschool in Amsterdam (an art and crafts school, which was renamed Gerrit Rietveld Academie from 1968 onward), where she studied in the industrial design department from 1964–1967. She didn’t finish the course, but she met her future husband, graphic and type designer Gerard Unger, there, and in 1968 they married.

In 1974 she started studying art history at the University of Amsterdam. She finished her studies in 1987, quite some time later, but the reason was simple: This student was working at the same time (and probably day and night). She was, for instance, at a very young age the director of the Amsterdam Fashion Academy (now called Vogue Academy), from 1973–1977, where she introduced novelties such as guest teachers and courses by stylists from the confection industry. Later she also taught at the Rotterdam Art Academy and the Rietveld Academie. Besides that, she was discovered as a good juror and adviser to many institutes, she organized exhibitions (fashion and design), and she wrote for some years for a Dutch newspaper. From 1980–1989, she was the chief editor of Bijvoorbeeld, a Dutch magazine for the applied arts, which under her leadership transformed from a rather dusty magazine into a lively and critical periodical with a post-modern avant-gardist look. In 1986 she collaborated with the renovated Dutch Textile Museum in Tilburg, curating the opening exhibition and writing the catalogue. Marjan, versatile, energetic, and ambitious, was everywhere and took every challenge to move things forward, always expressing her sharp opinions with humor but persuasiveness.

From 1991–1993, Marjan was the director of Dutch Form, the first Dutch Design Institute. In 1995 she became the head of the Master Vrije Vormgeving at the Sandberg Instituut in Amsterdam, a job she held until 2006. “Vrije vormgeving” is a pretty complicated concept. Translated literally, it means “free design.” The notion was invented by Marjan, in the period when she worked for Dutch Form and organized a couple of exhibitions about young Dutch design. She developed the idea of “free design” in a period when the boundaries between art and design were blurring, and discussions were being held about autonomous art versus functional design. The notion referred to the new tendency among designers to develop products in-house and produce these in small, often hand-made, series—a new view on design, initiated by the designers, not by industry or the market.

At the Sandberg Instituut, Marjan and her students had a wonderful time. She loved teaching, and she loved young talented people with all their crazy and beautiful ideas. Some of her students include Tejo Remy, Frank Tjepkema, Chequita Nahar, Evert Nijland, Uli Rapp, Terhi Tolvanen, Suzanne van Oirschot, Bas Bouman, Nick Renshaw, and Laura Braspenning, and there were many more. She would do everything to help them in their development. In the last period of her illness, her former students inundated her with flowers, chocolate, and other attentions as a sign of love, appreciation, and gratitude.

Jewelry was Marjan’s passion. In 1995, simultaneously with her new job at the Sandberg Instituut, she started her research about Dutch jewelry in the 20th century. In 2002 she made the exhibition Zonder Wrijving geen Glans (Without Friction no Shine) about Dutch jewelry in Centraal Museum in Utrecht, where she showed her first findings. In 2004 she published her 600-page book about Dutch jewelry in the 20th century, Het Nederlandse Sieraad in de 20ste Eeuw (only in Dutch), within the context of social, economic, political, and cultural developments in the Netherlands. The book was based on literature study and on fieldwork—like an archeologist she combed markets, antiques shops, and auctions searching for unknown work made by Dutch jewelers and filling the gap in museum collections. When she started her research, not much was known about Dutch jewelry before 1967. It was her mission to put the developments in Dutch jewelry in a historic perspective, and to dethrone the generation of the 1960s (Emmy van Leersum, Gijs Bakker, and others). After all, the Dutch had a tradition of making jewelry with a subdued character, from cheap materials. This was quite a dissenting opinion, but one that characterized Marjan as the iconoclast she wanted to be.

Doing scholarly research about jewelry was her drive to continue with her investigations, which eventually resulted in a thesis in 2010 (again in Dutch), Sieraad in Context (Jewelry in Context). Her versatility and her interest in fashion and design certainly contributed to the fact that she considered the whole span of jewelry, fashion, crafts, cheap accessories, ethnological, historical, fine jewelry, and art jewelry—the latter notion, by the way, was not one she preferred or used, and the same was true for the notion of contemporary jewelry. Marjan’s urge to observe jewelry in an inclusive way, not valuing one type above the other, and particularly waiving any distinction of quality, stood at the basis of this approach. In her view, the social and emotional values of jewelry are the strongest. In her Munich lecture in 2013 she said, “Jewelry feeds on human nature. Both makers and beholders of jewelry have to respect what feeds them, otherwise they have a hollow profession,” which is a wise statement.

On the occasion of her doctorate in 2010, she and her husband Gerard announced the gift of the main part of their jewelry collection to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the national museum of the Netherlands. The gift entailed about 500 pieces of mainly Dutch jewelry, from the 20th century. In the new Rijksmuseum, only a small part of the Unger collection, mostly jewelry from the period 1900–1960, is exhibited in the permanent Special Collections Department. Another choice from the Unger collection is part of a temporary exhibition in two showcases in the 20th century collection department.

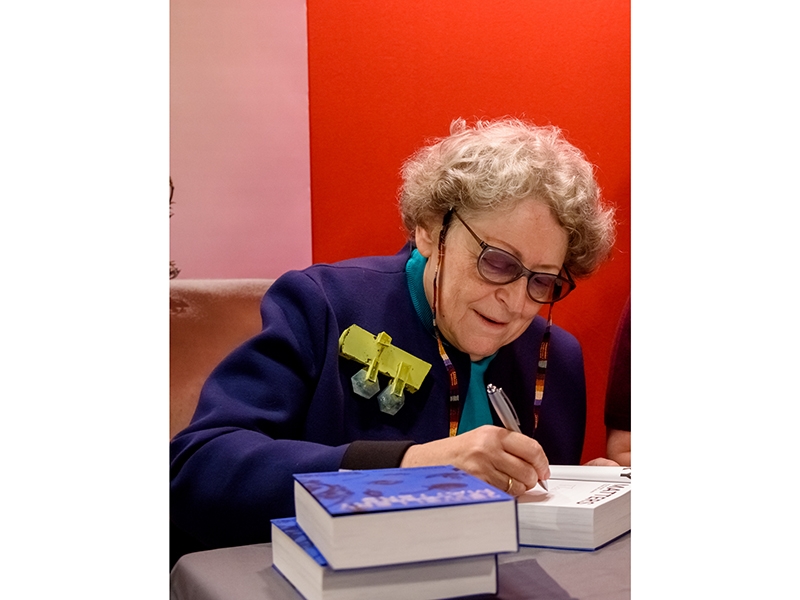

This gift resulted in a research project focused on the historic jewelry collection of the museum, on which Marjan collaborated with the museum’s jewelry curator Suzanne van Leeuwen. In 2017, they published the book Jewellery Matters (in English). The bulk of the book was written by Marjan as an extension and contextualization of her doctorate, focusing on the historic jewelry collection of the museum and observing it from an interdisciplinary viewpoint. In November 2017, Marjan and Suzanne organized the three-day-long, well-attended symposium Jewellery Matters at the Rijksmuseum.

By that time, it was already clear to those who knew Marjan that she was suffering from serious health problems. The last years of her life were not easy. In 2012, Marjan and Gerard lost their only daughter, and not long after that both Gerard and Marjan became seriously ill. Although Marjan healed, and could work on Jewellery Matters, she became ill again last year. Earlier this year, the Ungers donated another 200 pieces of jewelry to the Rijksmuseum, this time more recent pieces from the 1980s and later, for instance from Sandberg students. Also, her library and archives moved to the Rijksmuseum. Five days before her death, it was announced that the Ungers had donated their house, a post-modernist structure in Bussum by Mart van Schijndel, designed for them in 1981, to the Vereniging Hendrick de Keyser. The society, celebrating its 100th anniversary this year, aims to keep and protect special architecture in the Netherlands, and owns 423 premises. The Ungers gave everything they had away, and Marjan remained in control until the last minute of her life.

The Netherlands is much obliged to Marjan, who played a leading role in the history of late 20th century Dutch design and jewelry. Marjan was a warm-hearted woman, and a tough one. She loved to provoke colleagues in public discussions and could be confrontational. Marjan had wit; she liked making jokes particularly about herself. When she was called Mevrouw Vormgeving (Mrs. Design), moeke juweel (mother of jewelry), or, more respectfully, the queen of jewelry, she would chuckle. No matter what we called her, she was a phenomenon. It was a privilege to know her for so long, to work (and occasionally argue) with her, and to have lovely times at her house and elsewhere together with Gerard.

Many thanks to Sybrand Zijlstra (Marjan’s assistant for many years), Beppe Kessler (friend), Suzanne van Oirschot (former Sandberg student), Astrid Berens (Sieraad Art Fair), Suzanne van Leeuwen (Rijksmuseum), Pieter Elbers (Gerrit Rietveld Academie), and Klaartje Laan (Vereniging Hendrick de Keyser) for their help.