On May 19, 2025, Lam de Wolf passed away at the age of 76. As a child she was called Loes, as an artist she used the name Lam (her initials), and in the home where she spent her last years she became Lammy. She was a personality, even when words began to fail her. For people who knew her well, she was both a lamb and a wolf. She was an important innovator of Dutch jewelry and visual art, and an energetic and outspoken woman, artist, and teacher. Her work was recognized as pioneering and she had a breathtaking energy and speed of working and renewing. Textile was at the heart of Lam’s work. It was the beginning and the end.

Textile is the first material encounter of a human being—wrapped in cloth or dressed in a romper, a newborn is presented to the world. In a wicker basket, covered with colorful patches, Lam began her final journey. No flowers, no wreaths—but a donation of fabrics on her basket was requested. That is how she envisioned her final goodbye, for which she had already designed an “adieu” logo with a black heart long before she became ill.

Textile is a material that is close to people and serves many functions. It can keep you warm and give comfort. It is practical, useful, foldable, and flexible, suitable for handkerchiefs, sheets, and curtains, as tablecloths and cleaning rags, and as clothing. Lam was always dressed in beautiful garments (Yohji Yamamoto was her favorite fashion designer), shoes, and hats. In her work she was particularly interested in the mundanity of textiles, which she combined freely with other materials using flexible sticks and rubber tubes, paint, nails, staples, paper, plastic, and so on. She gave performances with wearable grids made of sticks and tubes, and made spatial jewelry as well as monumental wall installations and sculptures.

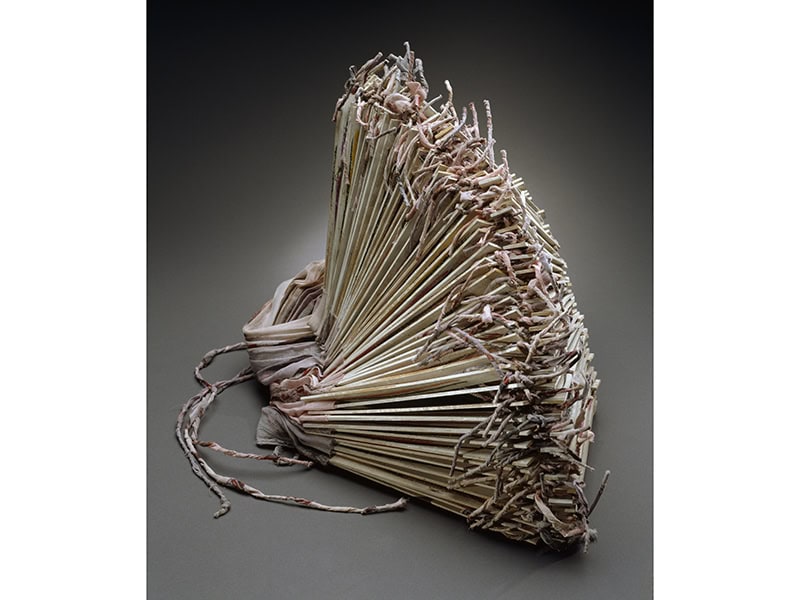

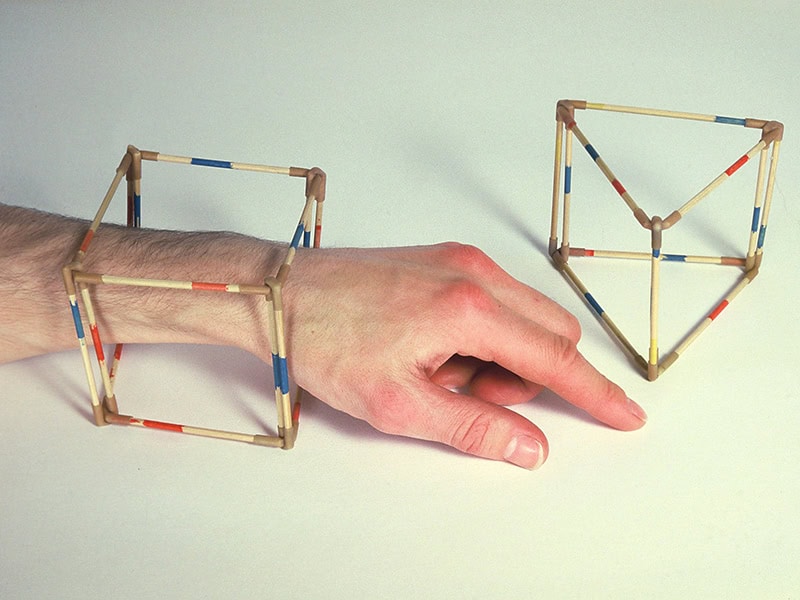

Lam was not a jewelry artist pur sang, nor was she a textile artist. She was rather a visual and word artist. At the academy she created large objects as well as brooches and wearable objects with a basic geometric form used in performances—all made from Mikado (from the game of pick-up sticks) and other sticks connected with silicone tubing. Size could not hold her back, nor function, nor destination. From the onset it was clear Lam didn’t fit in a box and didn’t like being pigeonholed.

After graduating from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy Monumental Textile Department, in 1981, she entered the jewelry world convincingly, leaving a lasting impression on everyone who encountered her work. Her first show was held at Galerie RA, in the summer of 1981, immediately after her graduation, and many more would follow in the next decades. Lam and RA’s gallerist, Paul Derrez, remained faithful to each other—even when she didn’t make jewelry anymore and concentrated on monumental and other visual art, which could also take the form of trousers, skirts, or puppets. Beautiful publications accompanied her work the entire way, demonstrating her hand, her choices, and her ideas.

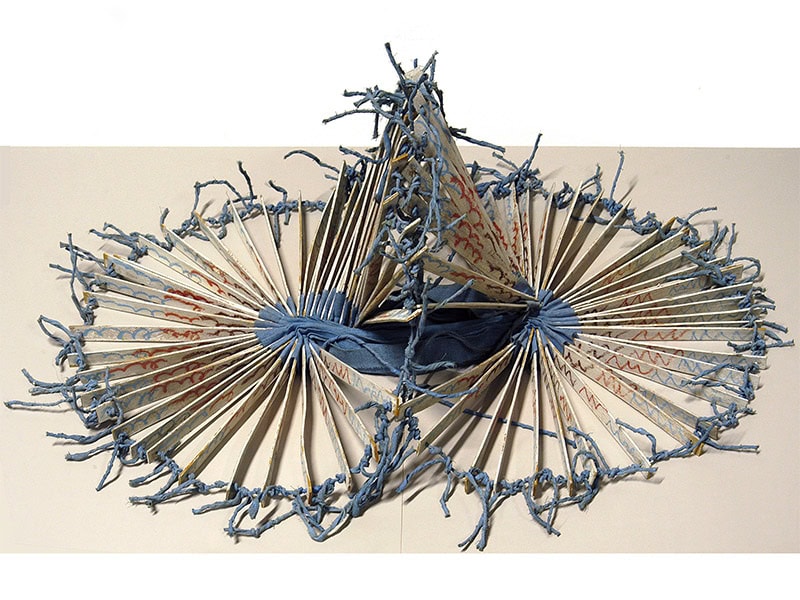

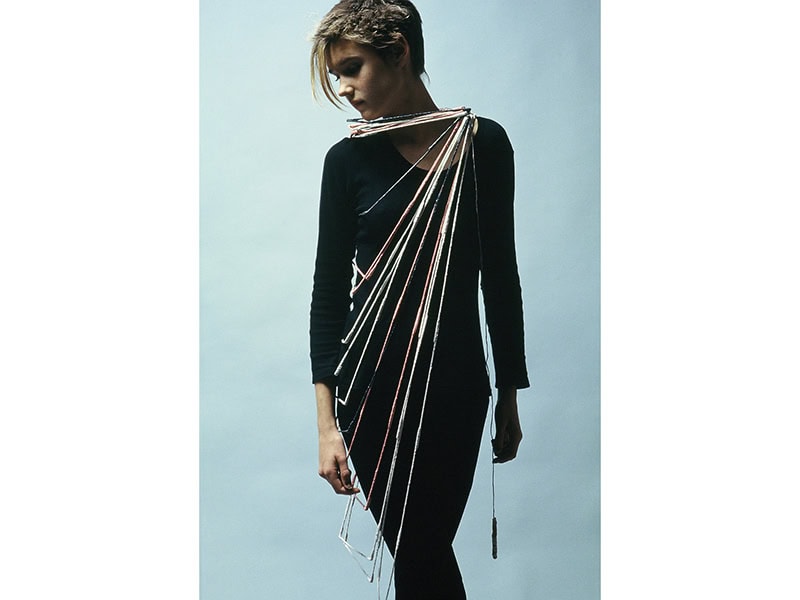

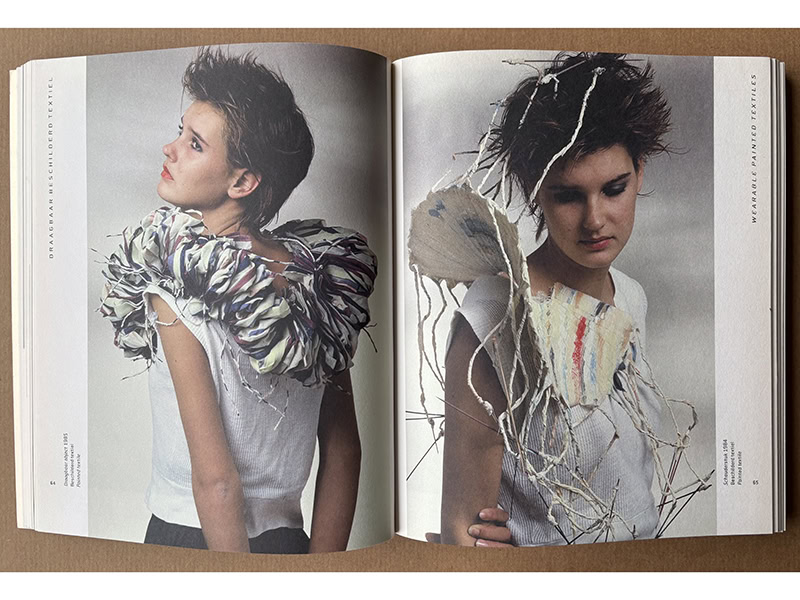

In the 1980s she was part of a new and inspirational movement in contemporary jewelry instigated by British and Dutch artists who were interested in flexibility, color, and soft materials. Lam called her first jewelry Wearable Objects, and so they were—though not easy-to-wear objects. She made bundles of repeating shapes, arcs, circles, squares, and triangles from sticks, wrapped with colored and dyed strips of textile. In case someone really wanted to wear a piece, she attached a long strand of dyed textile that ended in a little ball. The wearer could carry that ball in her pocket as a stress reliever. Some Wearable Objects could be closed at the back by tying long strips of textile together. Other pieces were worn across the body—one arm could be casually inserted through the sticks in the construction. She had fantastic photos taken of her pieces, worn by her favorite model to transmit the possibilities of wearing and the connection with the body. The most extravagant piece from this 1982 series encompassed the whole body from neck and shoulder to knees, like a kind of external skeleton. In wearing a Lam de Wolf necklace, you performed the piece.

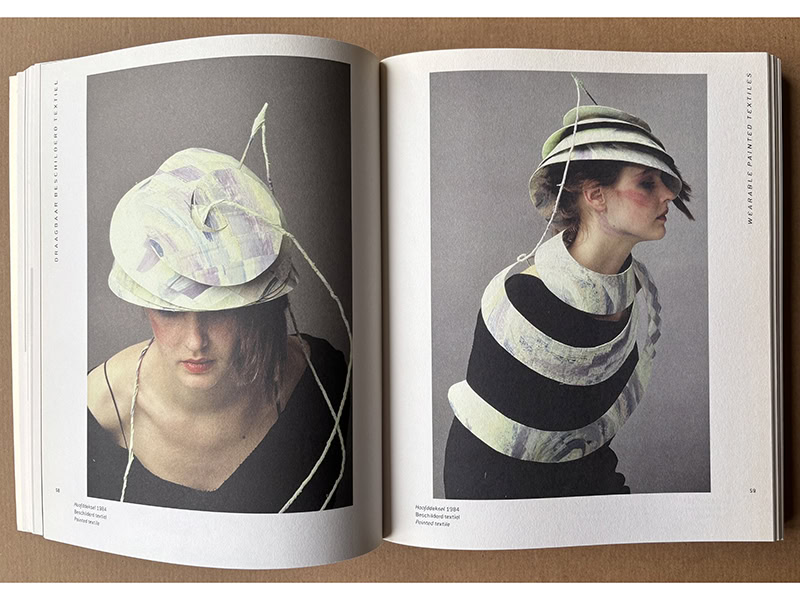

The jewelry that followed consisted solely of colorful and painted ribbon, knotted together to form pieces that looked like cloaks or stoles. Caps and collars made of painted silk and head and shoulder pieces combining painted textiles and wood or iron also came about. Sometimes the textile was starched with glue, depending on what the design needed.

The freshness of the colors she used and the baroqueness of the shapes was impressive—especially within the confines of the rather austere and strict Dutch jewelry context. There were references to 17th-century collars and costumes, but nothing too literal, nothing too obvious.

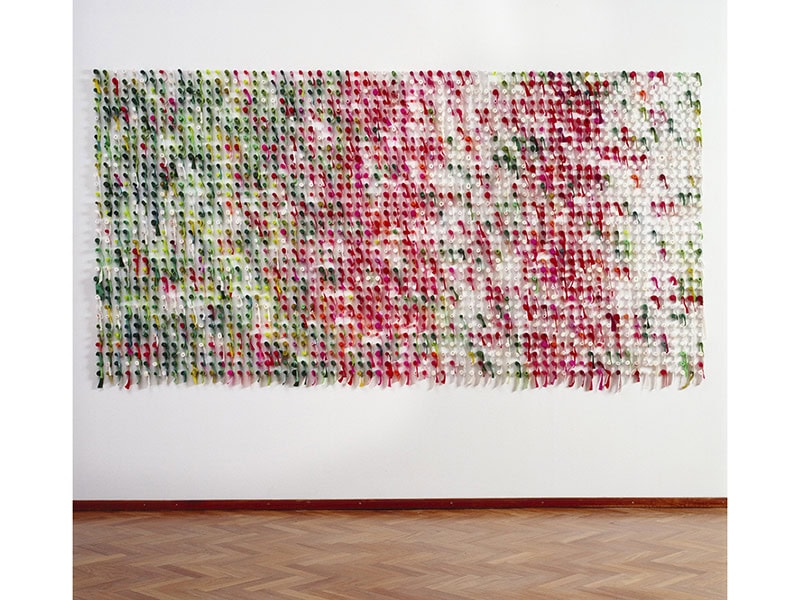

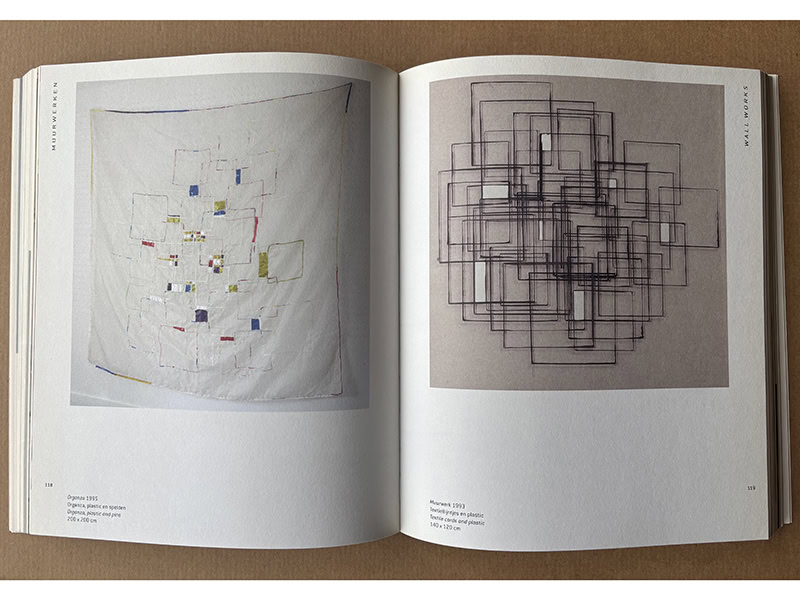

Around 1988–1990 she gradually moved to larger-scale autonomous work. Throughout her career the grid was there, spatially to make her early objects wearable or used for performances, and as a linear and mostly square or rectangular base on the wall for pins, on which small patches were attached with threads, knots, or tie-wraps. The grid provided order in compositions with fringes, cords, knots, and other irregularities, and became completely self-explanatory in the Hand Computer wall work made of colorful textile rolls. Sometimes her wall works[1] are like intriguing and sophisticated allusions to the De Stijl period in Dutch art of the 1920s. But her work was much freer and softer, using humble homespun-like materials such as textile strips, plastic foil, or even handkerchief borders, as well as needles, and it was as strong as can be—a liberation from sober lines and geometry.

Lam favored a pictorial approach, painting textiles in fresh colors and using them in compositions at the crossroads of two- and three-dimensionality. She never felt diminished by working with textiles. On the contrary, Lam made the viewer aware of the beauty of simple things: fringes, borders, threads were like her signature. She could hang painted patches from a line made of wood and rubber in such a way that the patches seemed to dance like laundry flapping on a clothesline in the wind.

In 2004 Lam started her ambitious Sinnerokken series, referencing the 15th- and 16th-century literary tradition of De Rhederijkers (Rhetoricians) and their Sinnespelen, which were poetical plays based on an aphorism or a phrase with a moral meaning. Lam’s Sinnerokken were long tube-shaped skirts on which she embroidered texts in combination with colored areas. The text fragments were carefully chosen from songs, poems, novels, and essays by Dutch and international authors. These skirts were like subtle messages for the wearer. For the opening of her exhibition, at Galerie RA, in February 2004, she invited people to walk in one of her skirts. I walked in one too. Maybe I was too nervous then, but I see only now that the text embroidered on it is “Parlando,” a song text by the Dutch artist Freek de Jonge about “while we still can, listen to stories from our mother, hugging her, feeding her with small bites of love.”[2] The text was so applicable to me at the time. This exhibition at RA also included her IJzeren Woorden (Iron Words) stapled on handkerchiefs, boxed, signed, and numbered. A word is never the same when you know what it looks like in irregular iron letters on a piece of cloth.

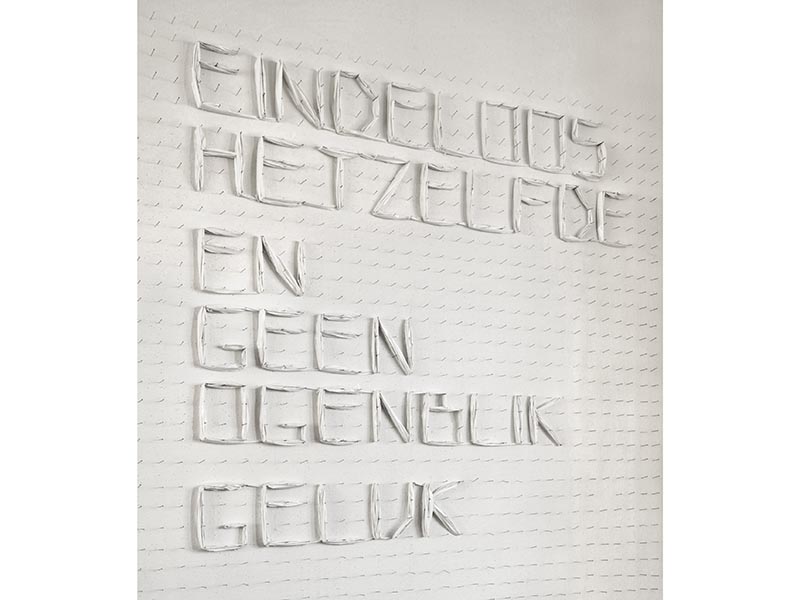

Over time, language and words became increasingly important and finally took on an independent role in Lam’s work. Words were like small poems, although she herself didn’t call them that. She invented words and turned words into image, played with words, unravelled them like she unravelled textiles and paper. Or she isolated syllables, turned them around, read from back to front, dissecting words and thus generating new emphases, finding new connections and new meanings. Her poetry (I like to call it that) and the art works she called “line words” are associative, moving, and funny, and they make you think. Examples include eindeloos hetzelfde en geen ogenblik gelijk (endlessly the same and no moment alike) and alles is al (everything is already), the last sentence repeated nine times in succession. This work was created in 2012 for the University of Amsterdam. The words in simple capital letters were made in lacquered film (a foil) and fastened with pins in a grid.

There’s so much more to write about the work of this overpowering artist. How she loved the exchange with the audience, how curious she was, how she would send questions to people like “what pressing question have you always wanted to ask me?” and “was there more in me than could be seen?,” how she liked to give something away in exchange for answers or participation in other ways, how she embroidered countless second-hand handkerchiefs with a word or a few and collected these in a printed Zakdoeken Boekje (Handkerchief Book, 2008). Lam’s work is filled with associations, and meanings that still talk to us—again and again. Her work is in many museum and private collections. Hopefully they will be shown to the public regularly, because her work is timeless and unforgettable. CODA Museum has announced that later this year it will semi-permanently install one of Lam’s favorite wall works—LangzaamEenzaamEenssaamSamenEe

Note

Lam de Wolf collaborated with several professional photographers over successive periods: Hogers & Versluys, Tom Haartsen, and René Gerritsen. She was probably one of the first artists to care about professional and artistic documentation of her jewelry. Hogers & Versluys used a special model who wore the jewelry, and Lam did the styling.

Photography was still analog and expensive. Digital photography became mainstream only around 2000. The first color photographs Lam had taken (by Hogers & Versluys) were slides, made with a Hasselblad 6 x 6 camera. This is a unique material (no negatives) and provided the best quality for printing. Nonetheless, as I wrote this remembrance it was very difficult to find good images of her work. There should be a Lam de Wolf archive full of the finest slides, but its location remains unclear, although many people have been looking for it. The CODA Museum Apeldoorn holds a Lam de Wolf archive, but it does not contain the large professional slides.

This is why we decided to include some smartphone photos of spreads from Lam’s book Monumentaal en Dichtbij (Voetnoot Publishers, Amsterdam, 2009). They are not ideal, but serve as a concession to give the reader a better impression of how her work fused with the body.

My heartfelt thanks to everyone who helped me in my search: Jos Houweling, Paul Derrez, Carin Reinders (director of CODA), Els Drummen (curator at CODA), Anneke Pijnappel (Voetnoot), Tom Haartsen, and Rob Versluys.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] See for instance Muurwerk (Wall Piece), 1990, silk, paper, wood, 94 ½ x 55 inches (240 x 140 cm); Organza, 1995, organza, plastic, pins, 78 ¾ x 78 ¾ inches (200 x 200 cm); Muurwerk (Wall Piece), 1993, textile cords, plastic, 55 x 47 ¼ inches (140 x 120 cm); and Leeg (Empty), 1996, handkerchief borders, cloth of gold.

[2] Freely drawn from Freek de Jonge, Parlando—nu Het Nog Kan, conducted at Theater Carré, in Amsterdam, together with the Metropole orchestra, 2002.