Morris died in 1896, concerned that the joy in craftsmanship he advocated had culminated in no more than “ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich.” Women subverted Arts and Crafts training to the production of multimedia propaganda for gender equality.

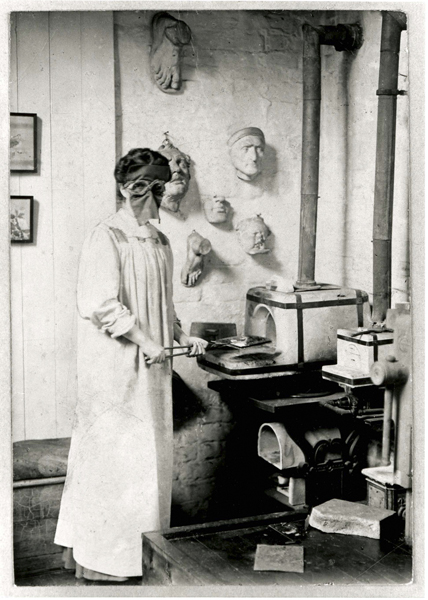

The creator of Angel of Hope, Ernestine Mills (1871–1959), trained in fine art at the Slade; she learned enameling and metal-work under the doyen of art enamelers, Alexander Fisher.

The pendant was made in London, commissioned from Mills by fellow members of the Kensington branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union—the suffragettes. The pendant was presented to the honorary secretary of the branch, Mrs. Louise Eates, in May 1909, on her release from serving a month in Holloway Prison. Eates had taken part in a lawful deputation of Votes for Women activists to Prime Minister Herbert Asquith. Asquith rejected the deputation and ordered arrests. Thus Louise Eates, wife of a doctor, was introduced to the deplorable state of justice for the powerless.

The Pendant

More can be read into the symbolist and miniaturist art of Mills than meets the eye. Here is one interpretation.

At top left, stars denote the misogynist night before the dreamed-of dawn of women’s rights. At top right, a barred window indicates the suffering of solitary confinement. A kneeling angel comforts the prisoner with a song of hope. (The angel alludes to a famous painting by Victorian artist George Frederic Watts entitled Hope, in which a blindfolded, kneeling woman listens intently to the note produced by the last string on her lyre.)

At the lowest point of the shield, a sliver of enamel is missing, suggesting misadventure. The pendant was probably accidentally dropped. Alternatively, wearer and pendant might have suffered assault in one of the increasingly violent clashes between suffragettes and police before World War I overtook the women’s revolution.

Identifying Suffrage Jewelry

This kaleidoscope of colors, allied to the popularity of colored stones in their own right, makes identification of suffrage jewelry problematic unless provenance can be traced. The Angel of Hope presentation was recorded in the Votes for Women periodical of May 14, 1909, as a “slender chain with stones of purple, green, and white,” where purple stood for dignity, white for purity, and green for hope.

Subsequently the WSPU colors were adopted by sections of the women’s movement in the United States, alongside the American colors of gold, white, and green or purple. Today’s redefining of “Green, White, Violet” as standing for “Give Women Votes,” or “Violet, Fern, White” as “Votes For Women” were not mainstream in Britain pre-1914. They may represent trans-Atlantic interpretation or possibly be just a myth.

Examples of Ernestine Mills’s work are displayed in the Museum of London, the Victoria and Albert Museum, and the Museums of Scotland, among other institutions. The Delaware Art Museum in the United States owns a dramatic enameled tondo by Mills, depicting a (symbolic suffragette) mermaid being suffocated by an (establishment) octopus; it measures 17.5 cm in diameter and is part of the Bancroft Collection.

Significant suffrage centenaries are on the horizon, including that of voting rights for propertied British women over 30 years of age in 2018, followed by equal citizenship with men in 2028 (2020 in the US). Will modern jewelers feel inspired to express solidarity with the campaign that tested women’s mettle and did not find it wanting?