Yi cun guang yin (An Inch of Time) is a series of four pieces—four rectangles, two in gold, two in jade—seemingly abstract, aloof, distant. It’s a title that, from a Western point of view, alludes to a work by Otto Künzli. Is it an homage? First impressions may not do justice to the object of their observation. Taking time and looking closer reveals a completely different nature of the work.

An Inch of Time is a series of four pieces. On one hand, An Inch of Time_01 and _02 are made of at least 18-karat gold. On the other, An Inch of Time_ 01 and _02 are jade of a pale, translucent green color without impurities, resembling the clear water of a lake.

The two pieces of An Inch of Time_01 are rectangles, measuring 37.5 x 24 mm. The golden rectangle is thin, at 0.2 mm, whereas the jade rectangle is 1 cm thick. The pieces of An Inch of Time_02 are more slabs or bars than rectangles, measuring 11 x 81 mm. Like _01, the golden slab is a thin 0.2 mm, whereas the jade slab is 1 cm thick.

All four pieces are designed as pendants. Each of these pieces could be worn individually. However, as the description above illustrates, all four pieces are entangled and need to be seen in a shared context.

A friend of mine pointed out that in 1995, Otto Künzli had already created a piece with a strikingly similar title: Otto millimetri d’amore, which can be translated either as “Eight millimeters of love” or as a pun, “Otto millimeters of love”. The piece is an outline of a heart, eight millimeters in height, meant to be worn as a pendant. Since Teng Fei studied in Germany and told me that she knows Otto Künzli in person, I am sure that she is aware of his work.

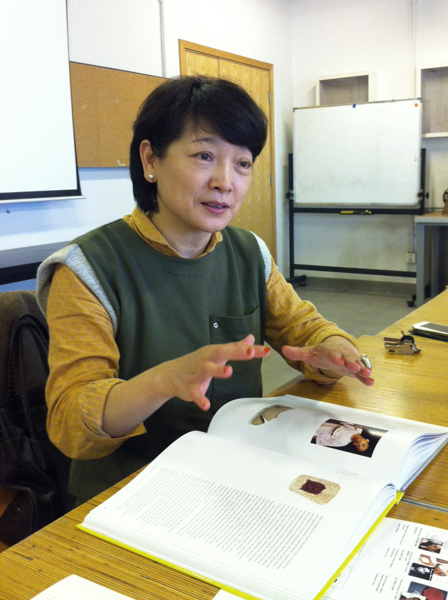

This text is my interpretation of Teng Fei’s work. Setting out to discuss potential East-West crossovers, and the possibility of plagiarism, I ended deep in Chinese cultural territory. The wealth of popular culture that surrounds and informs Teng Fei’s work, I found, far outweighs its anecdotal allegiance with the Swiss master’s. I got pieces of information from Teng Fei herself or found other texts she published. Based on these, I did extensive research about the cultural background by reading texts and talking to other Chinese, and finally got my own sense of Teng Fei’s work.

Cun and inches

While “An Inch of Time” is the best possible way to translate the Chinese title Yi cun guang yin, it is also, unfortunately, fundamentally misleading.

I literally stumbled over this issue because of the measurements of the piece An Inch of Time_01: 37.5 x 24 x 2 mm. Neither 37.5 nor 24 mm equals an inch. Could they be the equivalent of a cun, from the Chinese title?

A cun is a traditional Chinese unit of length and a way in acupuncture to measure and locate acupoints on a body. One of the traditional ways to measure it on a person’s body is to take the width of somebody’s thumb at the knuckle. Hence, originally it was an individualized measurement, and this is why it is also called a “Chinese anatomical inch.” In the twentieth century, however, the lengths were standardized to fit within the metric system, and in current Chinese usage it measures 33.3 mm (~1.312 inch). The fact that Teng Fei chose 37.5 mm instead of 33.3 mm might point to the fact that this “inch of time” belongs to a specific person and is not an anonymous inch.

Buying time

Yi cun guang yin yi cun jing, cun jin nan mai cun guang yin.

“One inch of time equals one inch of gold, one inch of gold hardly buys one inch of time.”

Proverbs are still in frequent use in China and illuminate the cultural background in a special way. The title of Teng Fei’s piece, and the proverb it refers to, suggests much more to a Chinese person than the literal sense of the words. It is an invitation to let one’s thoughts wander around, and this is what I will do in the following paragraphs.

The second part of the proverb—“one inch of gold hardly buys one inch of time”—addresses the question of whether time can be bought. We cannot buy another person’s lifetime; that time is theirs. Hence it is, in the truest sense of the word, measured in cun since it is tied to each specific person.

The first part of the proverb—“one inch of time equals one inch of gold”—suggests that time could be measured with a tape measure. Indeed, in ancient China, when a sundial was used to determine time, the change of the shadow length was measured in Chinese feet (chi). Feet were subdivided into cun. The time indicated by the shadow moving by a cun (thus about 1.3 inches) is a very short time. If a moment of time equals a piece of gold, this suggests that time is indeed something precious. Gold can be possessed. But time cannot be owned because it is impossible to save or stock. Even though that time is not ours, our daily language is full of phrases suggesting that time is in our possession (for example, “I don’t have time for that” or “I need to save time”).

Concluding my thoughts, it seems that time is ours and it is not, and now, just by studying the title of Teng Fei’s work closely, we have left the “planet” Otto millimetri d’amore, as well as the one of An Inch of Time, and traveled into a new “galaxy” of meaning, right into the center of Chinese culture.

Imbalance

Teng Fei says about her work: “People’s appetite today for materiality is such that size has become a valid measurement for wealth. For example, through physically stretching an ounce of gold, its density and appearance change. It is thought its desirability is augmented and its material value is believed to increase. However, even though the gold carries the same weight, the value has been lost.”

Teng Fei and the Chinese I talked to consider the rectangular shape as the more stable and balanced one. Here is (possibly) why: In Chinese symbolism, the square represents the Earth. It has to be noted that, in contrast to the English language, which differentiates between square and rectangle, the term “square” in Chinese denotes all four-sided shapes with four right angles, regardless of height-length ratios. Only later is a distinction made: A square is zhèng fāng, or a perfect square, while a rectangle is cháng fāng, a stretched square. In the Chinese mind the square, with its straight lines and sharp corners, represents laws and regulations. The importance of this is also illustrated in Chinese expressions. One is fāng fa, literally “way of the square.” The term originally meant the way to measure the size of a square or a rectangle, but in modern Chinese has been extended to mean “ways of doing things” or “method.” Another example is the adjective fāng zhèng, translated as “square and straight” and meaning “someone’s morality is like a square, with perfect straight lines and right angles.”

If, as I believe, the squat and stretched version of An Inch of Time are meant to signify two different states of the same thing, then it seems to me that the “way of doing things” laws and regulations have been overstretched from a rectangle into a slat and thus got imbalanced. Because of the vertical-horizontal illusion, people might think that the slab consists of more material and is thus heavier than the rectangle.

Overstretching time might mean packing more and more things into the same amount of time. Paradoxically, while more might have been done in the same time, less might have been achieved since the quality of what is done might be diminished. In conclusion, this is possibly why “though the gold carries the same weight, the value has been lost,” as Teng Fei states. The cun of time is not a cun anymore, since it got impersonalized.

Special relations

Teng Fei says this about her decision for the material: “The choice of gold and jade for An Inch of Time is the result of careful consideration. Yellow gold is a bit more rational, more precise, and thus closer to Western civilization, whereas jade is closer to the East. … In this group of works the gold is cut accurately and sharply, while the jade’s edges are more whole, softer and naturally formed. This in itself is a response to the differences between these cultures.”

Ren yang yu san nian, yu yang ren shi nian.

“A person takes care of jade for three years; the jade takes care of the person for 10 years.”

This proverb (mentioned by Teng Fei in our conversations) draws on the Chinese belief that jade which is handled frequently—in the sense of being touched or run over a person’s body—will improve in quality over the years. A low-quality piece of jade can thus become one of good quality. In the figurative sense, it means that putting time and care into educating oneself or another person can enhance this person’s character and abilities.

Then what exactly is the relation between jade and gold in China? How can gold be “more rational” than jade, as Teng Fei states? Looking at one of numerous proverbs related to this issue might shed some more light on this question.

Conceptual worth

The proverb Jin you jia, yu wu jia, “Gold has a price, jade is priceless,” is one that is often cited when talking about the relationship between jade and gold.

Gold as a material is a commodity. It is traded as commodity stocks and has a daily changing price based on supply and demand. A piece of pure gold is prized related to its weight. As far as I was told, in the Chinese mind gold represents a currency and, moreover, wealth.

Jade is not traded as commodity stocks, nor does its price depend on its weight. Jade is valued by the quality of the stone and of the carving. Jade has to be appreciated; in order to know its price, a lot of knowledge and experience is necessary. From a Confucian perspective, jade represents culture and an educated mind. Refining or “carving” a person’s character might take a lifetime, just like it takes a long time to carve jade. Moreover, while gold currency and fortune are countable, education or the formation of a person’s character are not, since they remain in the conceptual realm.

This might be one interpretation of why Teng Fei considers gold to be “more rational” than jade. For many Chinese, these connotations might be implicit in the choice of materials. For the Westerner, it will be like learning to appreciate a carved jade: It will take time and determination to get to its essence.

Precise and vague

Comparing how Teng Fei decided to shape the gold and the jade pieces is also illuminating. The pieces in gold have clear shaped edges and pointy corners, cut “accurately and sharply,” as Teng Fei puts it. Following the Chinese tradition, the jade has rounded edges and blunt corners; in the words of Teng Fei, “the jade’s edges are more whole, softer and naturally formed.” This, says Teng Fei, “is a response to the differences between these cultures [East and West].”

The Chinese, however, very rarely say “no”—at least not directly. To say “no” is considered impolite and blunt. Other phrasings will be used that paraphrase saying “no.” In sum, it is like saying no and not saying no. Visualizing this in a physical form, we find an object with rounded edges. This object has an edge and at the same time, it does not have an edge. You cannot hurt yourself or others with this object, just as the Chinese way of saying “no” in a paraphrased way helps all people to keep face since nobody gets affronted.

Conclusion

This was only a brief excursion into Teng Fei’s work. Much more could be said about jade or Chinese philosophy, many more proverbs could be cited, many more possible interpretations of the work could be found leading to more thoughts about values in our society and how they change, additional differences in cultures could be explored, and much more.

I consciously used a narrow analytical beam: My interest is in showing how Teng Fei’s contemporary work finds agency in a country with a nascent contemporary jewelry field but a rich and long material culture history. My interpretation might not be congruent with what Teng Fei wanted to communicate with her work, but I wonder if this is vital. From my point of view, it seems important that the work provides an entrance point to exploring Chinese culture and shows in what ways contemporary jewelry could contribute to that.

The work shows how a Chinese artist can create a conceptual piece pointing to another Western artist’s piece and training attention back to her own rich culture. Teng Fei’s piece bridges the gap between East and West, it is a search for her own cultural identity in an art form originally imported from the West. What it also shows, however, is that this work is not readily accessible for Westerners who insist on looking at it from a Western point of view and without interest in exploring its Chinese background. Looking from this perspective, we might still see four slabs and a reference to Otto Künzli’s work.

INDEX IMAGE: A sundial in the Forbidden City, or Imperial Palace, in Beijing, China, photo: Sputnikcccp, 2003 – licensed under creative commons