Driven by the uncertainty over the future of the monetary system, attention to the global gold market has been growing over the past few years. Like in any worldwide trade, its price is moved by a combination of supply, demand, and investor behavior. But unlike other assets, gold continues to be a safe-haven investment, and is considered a good hedge against inflation: Speculators as well as central banks favor it in times of economical/geopolitical turmoil because of its stability and easy liquidation. For instance, when the Great Recession hit, gold prices rose.

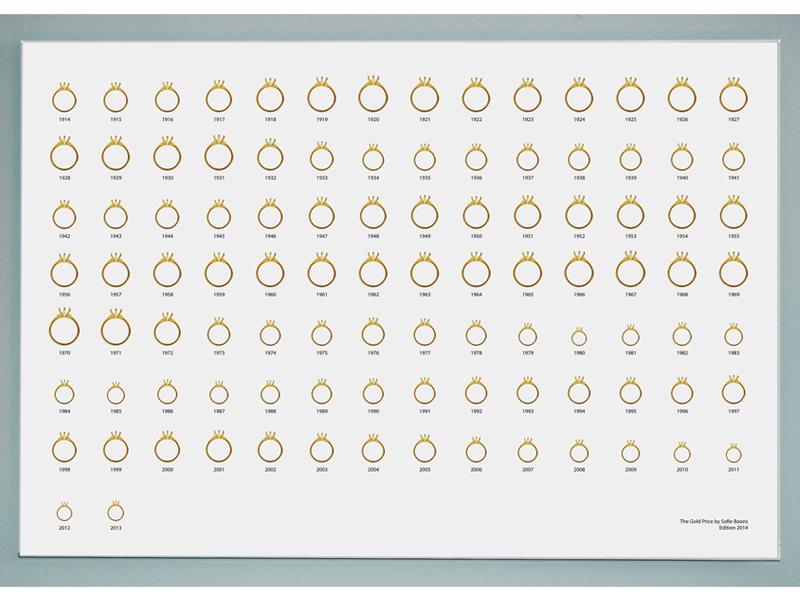

While reflecting on the above, creators in diverse fields have been inspired to depict these fluctuations through their work. In 2013 Sophie Boons summed up the fluctuations of the gold market since the last century (1913–2012) by visualizing the average gold annual prices in golden rings, resized according to the commercial ups and downs of the commodity. Employing similar methods, the designer Klemens Schillinger, in collaboration with Viennese jewelers A.E. Köchert Juweliere, presented a series of rings called Element 79—Aurum (gold is the 79th element on the periodic table) this year at Vienna Design Week. On a dedicated website, Schillinger also created an app that allows users to flick through time and watch the ring change in size/weight according to the amount of gold one could buy for the same amount of money throughout the years.

Both cases frame in a very literal way the relationship between the economy and gold jewelry. They follow a design process based upon the material’s financial facts and represent these through a common jewelry archetype. The formal language is intentionally reduced in order to highlight a “cause and effect” formula. These two examples portend to reduce the complex emotional projections that surround gold to simple statistical operations. Gold still endures as an emblem of value, and the way we deal with this seductive metal emotionally does not inform either work. This extra layer is present in the poetry of Gold Makes Blind (1980) by Otto Künzli—a bracelet featuring a ball of gold hidden in a black rubber tube that investigates our social and personal expectations about the ownership of gold, and that offers a better measure of the complex interplay that governs cultural value and material worth in a piece of jewelry.

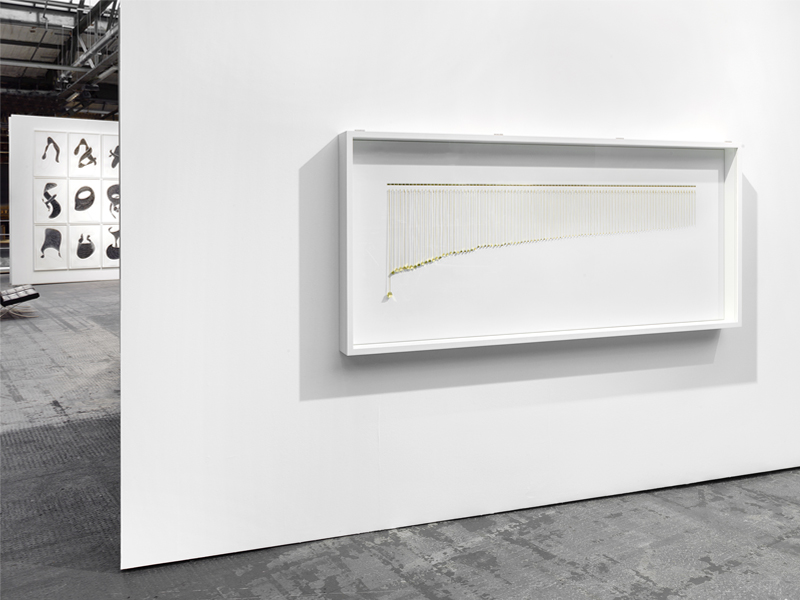

At the recent Art Berlin Contemporary (ABC) 2015 fair in Berlin, Alicja Kwade was more interested in leveraging the personal to engage with geopolitical concerns. This fine artist, mostly known for her sculptural work, created in collaboration with Georg Hornemann OHG a group of 97 necklaces exhibited inside a glass vitrine under the name GoldVolks. Hanging in a neat row from golden chains, gold cubes of decreasing size reflect the official gold holdings of the 97 listed countries they represent, according to the World Gold Council. Kwade translated national official stocks into hypothetical per capita ownership. The resulting chart opens with Switzerland (129 gr) and concludes with Yemen (0.06 gr). If one believes the press release, there is a participatory element to this project: “…Kwade will ask visitors to wear a chain, perhaps their own country’s. Chains of countries that no one is willing to represent will remain inside the case. Wearing one of the gold pendants may inspire a feeling of sharing in a country’s wealth, even if its prosperity is not necessarily enjoyed by all residents.”[1] Visitors were encouraged to pick up and wear their country’s pendants during the fair, and gaps appeared in the vitrine as people got involved in the project (see the Instagram feed #goldvolks). They could also buy them for 2,600–26,000€ according to size/weight.

At the recent Art Berlin Contemporary (ABC) 2015 fair in Berlin, Alicja Kwade was more interested in leveraging the personal to engage with geopolitical concerns. This fine artist, mostly known for her sculptural work, created in collaboration with Georg Hornemann OHG a group of 97 necklaces exhibited inside a glass vitrine under the name GoldVolks. Hanging in a neat row from golden chains, gold cubes of decreasing size reflect the official gold holdings of the 97 listed countries they represent, according to the World Gold Council. Kwade translated national official stocks into hypothetical per capita ownership. The resulting chart opens with Switzerland (129 gr) and concludes with Yemen (0.06 gr). If one believes the press release, there is a participatory element to this project: “…Kwade will ask visitors to wear a chain, perhaps their own country’s. Chains of countries that no one is willing to represent will remain inside the case. Wearing one of the gold pendants may inspire a feeling of sharing in a country’s wealth, even if its prosperity is not necessarily enjoyed by all residents.”[1] Visitors were encouraged to pick up and wear their country’s pendants during the fair, and gaps appeared in the vitrine as people got involved in the project (see the Instagram feed #goldvolks). They could also buy them for 2,600–26,000€ according to size/weight.

Breaking up gold holding per capita is a clever way to visualize relative hypothetical wealth, but I am not convinced that it either instilled a sense of participation in a country’s wealth or that it actually functioned as a symbolic staging of equal distribution/access. The gesture of wearing cubes of gold around one’s neck in the middle of a cosmopolitan art fair in Berlin doesn’t seem to build much inequality awareness. In reality, the installation—like the work of Boons and Schillinger—lets math do the talking, and does not really provide either the means to translate it back into world histories or bother to jolt viewers/wearers out of their comfort zone. The cubes highlight differences across borders rather than create a feeling of wealth-sharing with fellow citizens, and their impact relies on perpetuating our faith in gold: that cherished metal.

INDEX IMAGE: Alicja Kwade, GoldVolks, 2015, 97 gold cubes and chains, courtesy of Alicja Kwade, König Gallery, and Georg Hornemann OHG, photo: Martin Klimas

[1] Press release, König Galerie, ABC 2015, Berlin