Alexander Blank’s jewelry frequently riffs on the notion of pop-cultural-icons-as-cameo-portraits: bashed yellow “smiley-face” brooches, “skull” pendants seemingly made of the fossilized remains of Daffy Duck and the Tasmanian Devil and, in this piece, a roughly carved deer horn pendant in the shape of the Playboy “rabbit” logo. In this photo, Blank’s friend and fellow artist Stefan Heuser wears the necklace, staged in the manner that Heuser often photographs himself wearing his own, unusual jewelry designs to elaborate on or embellish their meaning.

Hugh Hefner founded Playboy magazine in 1953 with the mission of creating a “gentlemen’s magazine” pandering to an emergent, post-World War II, Mad Men-era ideal of masculinity in the United States. In the magazine’s earliest years, this was predicated upon a strict return to the traditional gender roles that had been disrupted during the war, when women joined professions and the military, and the confidence they gained in the workplace spilled over into their personal lives as well. Like American post-war culture in general, Playboy—regardless of Hefner’s revisionist assertions to the contrary[1]—sought to promote a modern patriarchal lifestyle wherein women maintained the new sexual freedoms they flaunted during the war, but otherwise were expected to return to a nostalgic, kittenish (and mostly fictional) pre-WWII femininity.[2]

Hefner believed that the Playmate should reflect the compliant and accessible “girl next door” with what he called a “seduction-is-imminent” look,[3] not so much demonstrating her own desire, but mirroring that of her (presumed, male) viewer. Playboy’s female pin-ups cultivated this look in ways that set the standard for the next few decades: soft, smiling, compliant women whose postures opened them up—teasingly, never showing their genitalia in the manner of more hardcore pornographic material, and so suitable to the wide readership Playboy sought—and welcomed the viewer’s gaze and sexual advance.

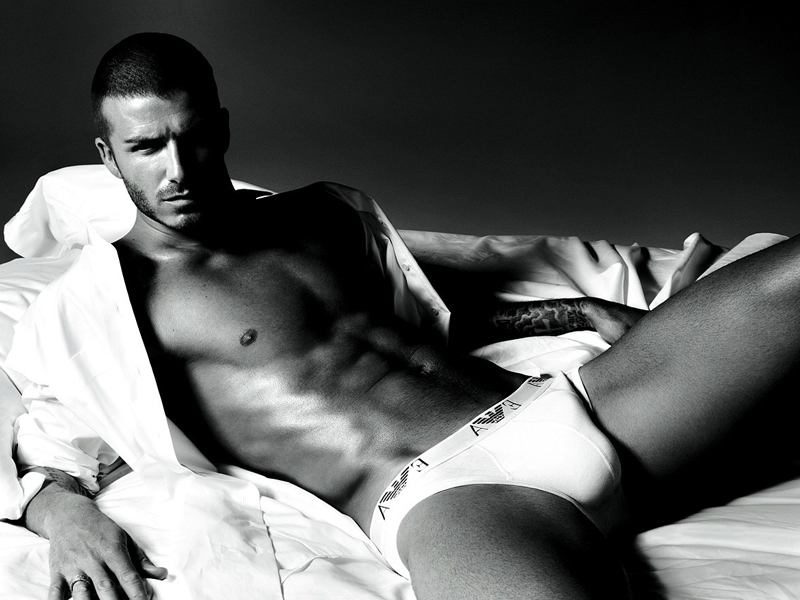

But when Stefan Heuser takes on the pose and attitude of the female “bunnies” represented within Playboy rather than the male “playboy-readers” to whom their overtures were directed (and for whom the bow-tied Playboy rabbit logo is a winking stand-in), one is reminded of how rare such supine, soft, sexualized depictions of adult men’s bodies are in pop-culture history. Both the rough-hewn “stag” horn from which Blank’s cosmopolitan Bunny has been carved and the passively seductive pose of the male model mix messages of stereotypically masculine and feminine sexuality. Heuser, like Blank’s pendant, is simultaneously bunny and playboy, blurring the binary gender construct on which both the object’s and the image’s pop-cultural references are predicated.

In 1982, renowned cinema scholar Richard Dyer famously analyzed the male pin-up and concluded that its rarity in pop culture—unlike men in hardcore pornography, where sexualized men can more easily be shown as active and dominant, “straining and striving”—might be chalked up to the dangerous paradoxes of masculinity it represents: “Looked at but pretending not to be, still yet asserting movement, phallic but weedy—there is seldom anything easy about such imagery [ … which] does violence to the codes of who looks and who is looked at (and how).”[4]

Yet Dyer’s queer, feminist analyses of pop culture were themselves dedicated to the subversive pleasures possible when these “codes” are broken. In the 30-plus years that have transpired since Dyer’s essay, we have become more accustomed to seeing ideal, masculine bodies in mass culture represented in historically “feminine” ways, and aimed at desiring, neglected heterosexual female and queer gazes—sometimes reveling in them, sometimes awkwardly capitulating to them. (Witness, for example, the differences between David Beckham’s 2007 advertisements for Emporio Armani and poor Tom Hiddleston’s pictorial for the August 2016 issue of W as recent examples of the former and latter.) Heuser’s portrait with Blank’s Bunny is a reminder of the spectrum of tantalizing, playful possibilities in between.

But, for all these contemporary points of reference, I must admit that the more time I spent with Heuser and Blank, the further back my art historian’s mind went—coincidentally (or not?), to the Hellenistic Barberini Faun, housed in Munich’s Glyptothek. Both Heuser and Blank studied with Otto Künzli at Munich’s Academy of Fine Arts, blocks away from the Glyptothek’s rich collection of classical Western art—so it wouldn’t be at all surprising if this strikingly beautiful, ancient sculpture was, consciously or unconsciously, a point of reference for this image.

Like many classical art scholars before him, John Onians considered the Barberini Faun a cautionary figure; its immodest, drunken pose is “the antithesis of the erect and disciplined alertness” that the faun’s magnificent ideal of Greek masculinity only physically, and thus incompletely, represents.[5] But in her more recent scholarship on the sculpture, art historian Jean Sorabella recuperates the figure’s literary bona fides and languid sexuality. Sorabella argues that the faun’s heroism and vulnerability, potency and passivity are not mutually exclusive: Besides his ideal beauty being clearly modeled after athletes and warriors, his receptive demeanor reflects the noble repose of the symposiast as much as the comical decadence of the satyr, rendered in a way that cannot help but provoke desire even if, like the layers of mixed messages it employs, those desires are complex and conflicted.[6]

Heuser’s pointed, come-hither gaze seems neither sleepy nor intoxicated, and his smooth, boyish physique is quite different from the bulky, athletic body of the Glyptothek’s faun. Regardless, this ancient example of heroic yet vulnerable, silly yet dead-sexy masculinity is a parallel to and a reminder of the longer history of the same range of masculinities with which Blank and Heuser’s 21st-century version—and our 21st-century culture—enticingly toys. Blank’s Bunny pendant is the delightful, excessive cherry atop Heuser’s slice of cheesecake, begging further discourse on jewelry’s myriad meanings in the context of our shifting notions of gender and sexuality.

[1] In the decades since he founded Playboy, Hefner has alleged that the magazine helped bring about the sexual revolution, was progressive, even feminist (once his daughter took over the magazine). But it’s easy to read the earliest issues and see how directly he’s being sexist, even misogynist in the way his writing addresses women.

[2] In Chapter 6 of my book, Pin-Up Grrrls: Feminism, Sexuality, Popular Culture (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006), I offer a more extensive and more nuanced history of Playboy in the wake of World War II.

[3] See Russell Miller’s Bunny: The Real Story of Playboy (New York: Plume, 1984), 49–52.

[4] Richard Dyer, “Don’t Look Now: Richard Dyer examines the instabilities of the male pin-up,” Screen 23, nos. 3/4 (1982): 63.

[5] John Onians, Classical Art and the Cultures of Greece and Rome (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999), 140.

[6] See Jean Sorabella, “A Satyr for Midas: The Barberini Faun and Hellenistic Royal Patronage,” Classical Antiquity 26, no. 2 (October 2007): 219–248.