In her essay In search of “Jewellery”, Dempf states, “contemporary jewellery in Germany is, above all, international”. I don’t dispute this for one second and would expand the statement to say that contemporary jewellery in Europe is international. Therefore I was curious to see if and how the categorisation of nationalism could be presented as some form of collected identity within in an art jewellery context.

It was good that the work in the exhibition had not been physically segregated into Belgian, German and Portuguese divisions, and the extent of the exhibition’s curatorial reference to representative country was having either (B) (D) or (P) after the artist’s name on the exhibit label. I can’t fault the quality and craftsmanship of the selected work; and the consideration to select work not only from established artists but also work that represented a younger generation including recent and ‘soon to be’ graduates, thus serving as a worthy introduction and overview of work produced by the three countries. However, without a theoretical framework to contextualise the overall exhibition- I found it not always easy to engage with the ideas behind individual pieces. Personally I would have liked to have had access to some contextual information that went beyond each label content of name, country represented, title and materials. Nevertheless the exhibition presented, and delightfully so, a Babel hall of many different visual languages, accents and vernacular, some of which I understood and some of which the meanings were lost without translation or context. For example I was intrigued by a piece by Nelly Van Oost (B), presented as two large-scale posters hung on the wall accompanying a necklace of chains in an adjacent display case. I was curious as to under what request people had sent chains to Van Oost, and were all the chains included in the final piece? So without any presence of information at the exhibition and my curiosity getting the better of me – I contacted her directly and was duly supplied with the information that I was looking for. Thanks Nelly.

I’ve always been drawn to Daniel Kruger’s (D) work and the variety of manifestations that it assumes and inhabits, intrigued by the otherworldliness of the brooches by Pedro Sequeira (P) and grounded by a sense of strength and assurance when I look at the necklaces by Dorothea Prühl (D).

Daniel Kruger, Necklace, 2011, Enamel on copper, silver filigree, photo: U. Beier

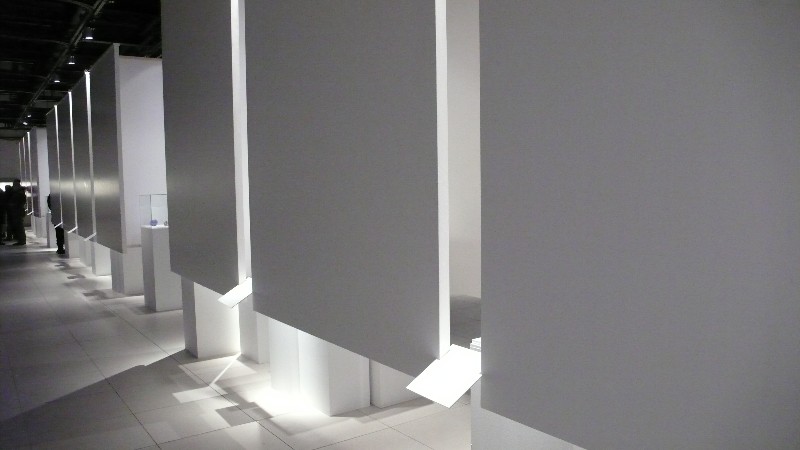

The exhibition was held at the Les Anciens Abattoirs, a renovated mid nineteen century slaughterhouse that allows for an impressive hall space whilst retaining some of its original architectural features. Works were displayed in a variety of ways; on the wall sans vitrine and occasionally as an installation in a way that one could imagine that the artist had strictly specified the layout. There were several suspended glass top boxes that seemed purposed built to hang from the original over-head industrial fittings. A display installation ran length-ways down the center of the space, creating a long walled interior space with a series of narrow openings so the viewer could singly look through to view work held within the internal void. The anticipated approach to each new ‘window’ our gaze falling upon each new offering, the heightened sense of cinematic scopophilia. Or maybe that’s just me?

I enjoyed the exhibition and being a delegate at the one-day symposium listening to Jo Bloxham and Jivan Astfalck talk each about their practice and dialogues around jewellery within a broader context of art. And each of the invited curators outlined the history of contemporary jewellery from the 1970s to present day from a national perspective of Belgium, Germany and Portugal, but I left the exhibition feeling ‘wanting’ of something that was missing. Hélène Martiat, the exhibition curator, presented the exhibition as an overview on current design and “the new issues faced by artists”. But as I left Belgium and travelled home, I asked myself “is much of art jewellery in danger of becoming, or perhaps already is, a luxury item forsaking; its political and revolutionary heritage?”

I do not ask this question of others without having first asked it of myself- and I will not try and hide the fact that when I look at many of my past work- that my direction could be described as inward looking and at times, one might argue, self indulgent.

So what happened to the political edge that was boldly championed by art jewellery in the late 1970s and 1980s? Returning to Dempf’s previous cited essay, “Germany and its neighbouring countries at the end of the 1970s and 1980s was revolutionary and provocative” and she suggests that for today’s jewellers, that provocation is not a “primary aim”. And I think that this is true to some extent in that the Baby Boom jewellers’ formative years were lived against a cultural backdrop of the Paris May riots, The Vietnam War, Civil Rights campaign, Watergate, Women’s Liberation groups, Prague Spring, Beatlemania, Motown (as well as the assassination of JFK, anti war protests, human rights campaign, In Cold Blood, the environmental movement, CND, Easy Rider, the Cold war, sexual freedom, social experiments, the first scripted interracial kiss on TV – Star Trek episode # 65, Tokyo Story and much more); dramatic social change captured and disseminated through the then new global medium of television. Baby Boomers are associated with a rejection and the redefining of traditional values held by their parents, and in Europe and America they were a generation who believed in change and empowerment. The Baby Boomer Generation handed down the freedom of individual expression and this ideology was translated through the work of Heron, Van Leersum and Künzli.

Perhaps I’m being true to my own Generation X cynical sensibilities but it seems that today’s revolutionary flag is not always being waved by todays’ art jewellers as it was in the late 1970s and 1980s; but sometimes more by commercially driven jewellery enterprises that are advocating both responsible and ethical design in response to some of the human right issues that are associated with and championed by the Baby Boomer Generation. Traditional values of jewellery were questioned by the likes of Knobel, Degen, Broadhead and Boekhoudt whilst rejecting gold and its capitalist connotations. But in an expected turnaround, in some sectors of today’s jewellery industry, the use and trade of gold is now being used to address and promote environmental sustainability and uphold human rights for exploited miners and gem workers (adults and children). So maybe it is Generation Y jewellers like Van Oost, and future Generation Z jewellers, born into an era of globalisation highly connected by media technologies, who are in and who will take up the revolution and actions like the Slow Movement – placing value in people, addressing the needs of the collective rather than the individual, living a connected live. In short, those who went before us helped to shape the present and many of us now have the luxury of choice and the choice of luxury, but let’s each not forget our place in the bigger picture; art jewellery is international and we are in it together.

Mah Rana studied jewellery at Royal College of Art and psychology at London Metropolitan University.

She is a currently a research fellow at London Metropolitan University. Jewelleryislife.com

“In John Brahm’s 1946 film The Locket, Nancy suffers emotional trauma from a childhood incident in which she was accused of stealing a friend’s locket. As she slowly goes mad, she destroys the men who love her. My own attachment to jewellery is very strong, but I hope with not such devastating consequences.”