Looking at two very different makers, this article explores adornment in installation works and the ways by which optical qualities such as luster, reflection, tactility, and pattern harken back to conversations on jewelry, the body, and wearability.

1.

First and foremost, is there such a thing as “jewelry for spaces”? I don’t mean the many jewelry-like works that decorate sites, from architecturally sized necklaces in public spaces (such as the Inges Idee 2004 work for a shopping center parking garage in Düsseldorf) to the organization of products in the field of interior design for the purposes of comfort and beauty. I mean works that add both decoration and content to an architectural space in a manner that allows the viewer to critically consider what it means to adorn. Amelia Toelke and Kristi Sword, two emerging makers in the field of jewelry and metalsmithing, address what it means to adorn sites with the language of jewelry (rather than simply decorating with large-scale jewelry itself) and, in turn, develop a conversation between space and adornment that is rife with content.

Amelia Toelke’s recent work addresses decoration, pattern, and surface in an array of ways, specifically focusing on wall-based installation works. While other pieces within the same show (Cloud Forms and Transom) are safe constructions of the decorative florals and baroque-style forms ever rampant in our field, Dragonfruit is her pièce de résistance. In it, she abstracts badges, ribbons, and banners into oversized, fuchsia-colored reflexive surfaces that refract and bleed into the gallery space. Much like installations by artist Laura Hughes, Toelke’s reflections saturate the space and interrupt your experience in the gallery, allowing for an ever-changing experience with the work. Bathed in color and casting a look at your reflection as you pass by a panel, you become a part of the work itself. Repurposing the traditional forms of jewelry, badge, and banner and reassembling them into a hybrid mash-up of pattern and repetition, Dragonfruit calls to the history of the wearable symbol, the quality and luster of the jewel-toned, and the malleability of contemporary sculptural objects.

What does it mean to create new, fresh symbols from the reassignment and reorganization of traditional ones? Honor, celebration, success are now jewel-toned and “supersized.” They don’t lie upon your body, but rather reflect onto it from the vantage point of the architecture itself. The piece practically exclaims its position of excellence, full with symbols that give cause for its own celebration. Much of Toelke’s earlier badge work includes jewelry-specific details: a bail, decorative flourish, chains and clasps. In Dragonfruit, the language is wholly digital: laser-cut clip art etched with a gridded pattern that appears to pixelate the pieces, one by one. This work acknowledges the language of decoration in the contemporary moment while still paying homage to traditional forms and shapes.

2.

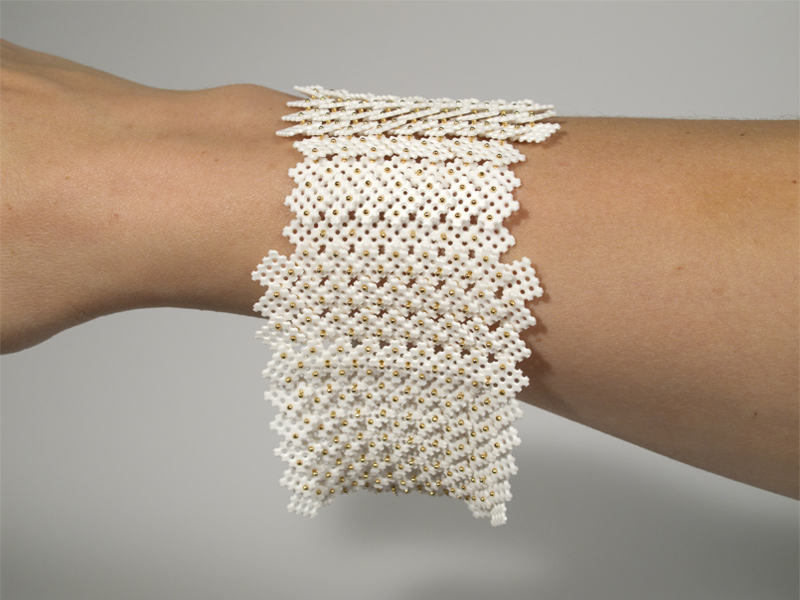

Kristi Sword, a maker of both jewelry and installation-based objects, approaches ideas of surface beyond the spectrum of traditional symbols and instead toward tactility, surface structure, and patterning. In her body of work called Quick Count Drawings, Sword expands on notions of surface, faceting, and the precision of fabrication with wall-based installation works. Comprised of thousands of miniature segments of plastic mesh sheeting, Sword’s surfaces are lush and evocative hills and valleys that both absorb and reflect light in lustrous ways. Even when patch-worked and seemingly flat against a gallery wall, the pieces become faceted and angular, a topography of small elements coming together as one complete, nearly vibrating, body. The dense white plastic is painstakingly pinned together with silver or gold, becoming a tactile, beaded surface asking to be touched. When a piece is touched, the connected elements sink into one another, compressing the surface much like pushing your fingers through a heavily sequined dress. Similarly to how these sculptural works function in the gallery space, Sword has a body of wearable work using the same mesh sheeting materials, exploring forms and movement on the body through the same tactile methods of building.

Like Amelia Toelke’s work, Sword’s sculptural pieces exist on the wall, removing themselves from the immediacy of wearability and adorning the architectural space in which they exist. Where Toelke’s work used symbols rife with content and jewel-toned surfaces saturated with color, reflection, and luster, Sword’s work tackles space, surface, and adornment with subtle connections to light and volume. She segments and interrupts ready-patterned material with her meticulous fabrication, creating surfaces that seem to mimic pavéd and bead-set stones in various states of volume and flatness. In Quick Count Drawing pt. 3, she highlights the peak of each “facet” with gold or silver, which reflects light from the edge much like a cut stone. In pt. 2, traditional quilting language and references to cross-stitch fade and pixelate into abstracted bunches of dense and not dense. While there are elements of her work that reference traditional jewelry in their process, and consideration for the interplay between surface and form, her work does not attempt to mimic the traditional decorative elements of jewelry itself.

Going back to our opening question—“is there such thing as jewelry for spaces?”—we must ask ourselves if these works are both in conversation with the field of jewelry and with adornment of an architectural space. The ways by which Toelke’s and Sword’s works occupy space in the gallery set them apart from either straightforward wall-based sculpture or installation art. Indeed, their work addresses adornment in a manner that ties them to the field of contemporary jewelry: the visual qualities of reflection, luster, texture, the slight tip-of-the-tongue recognition of the traditional jewelry properties of a pavé setting, the ribbon of a badge, or the saturation and gleam of a stone. What makes this work exciting is its ability to adopt the languages of adornment and decoration, and find new methods to expand jewelry practices into a broader spectrum of form and format. The “jewelry perspective” of making and viewing work means taking what is conceptually and formally significant at the core of our field and creating fresh, critical venues by which to discuss it. These works, among many others, give us the freedom to reconsider what being a contemporary maker in our field looks like.

[1] Joseph A. Amato, Surfaces: A History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).