Author jewelry seems to be changing its appearance in the practice of today‘s younger generation of makers. Jewelers are reevaluating their relationship to the medium, its spatial boundaries, the possibilities of its presentation, and the relationship between jewelry and the viewer/wearer. This new work often balances on the edge between fine and applied arts. Some of these works on the edge can no longer be perceived as jewelry in the conventional sense of the word. They push the boundaries of author jewelry toward new forms and ways of engaging with the audience, toward a new performativity, by creating authentic situations and processes that allow the audience to actively participate in the work and thus become part of it.

The impulse for this essay was the jewelry works of emerging artists that are no longer just jewelry, but neither can they be understood as sculpture, painting, performance, or installation in the traditional sense. These works exceed the traditional art categorization by intersecting with other media. They do not consider static form as their final form, but rather open a discussion and space to explore ways and means of active communication and engagement with the viewer/wearer in the context of the work. They build on the conceptual jewelry tendencies of the 20th century represented by Otto Künzli, Peter Skubic, and Bernhard Schobinger, among others, but their openness lies in their hybridity and performativity against different cultural and social backgrounds. Where is the place for these works? How do they reflect upon author jewelry, and what is their significance for expanding the perception and new contexts of the medium?

Performativity in jewelry is often described and perceived as (1) the effect of its material, i.e., immediate material properties such as color, luster, surface, weight, temperature, as well as properties associated with cultural and social conventions such as value and pricing. Under the concept of performativity also falls (2) the way jewelry is used by the wearer or owner, i.e., to represent in public, as a personal talisman, adornment, or commodity. In a wider context, (3) performativity can be understood as the process by which the work was created. In other words, performativity involves issues of process, function, changeability, significance, event, or program, and therefore can be interpreted as what jewelry does rather than what it is.

This article explores more closely performativity in jewelry as a process of making. In most cases, the process of making takes place among the four walls of the artist’s studio, and the viewer is confronted solely with its outcome. But what if the work is created directly in the exhibition space and becomes a performance or event?

The primary performative value of jewelry lies in its materiality—the ability to change its appearance, surface, or color, or its form due to use, time, and environmental exposure. However, if the change of the form, surface, or color is the result of an intended intervention of the environment, author, or audience, the perception of permanent and changeless form is subject to the authentic experience here and now.

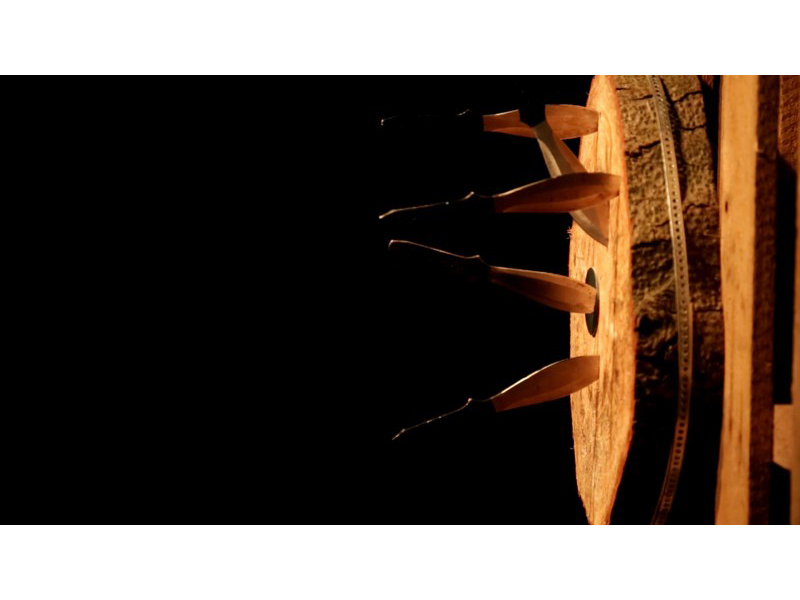

A prime example of this is the work Wurfmesser (Throwing Knives), by the German jeweler Gisbert Stach. The performance of Wurfmesser was held at announced times in a closed underpass during Munich Jewelry Week 2015.[1] Stach, as the author of the performance, threw knives, trying to stab a circular aluminum brooch hanging on a wooden wall. The viewer stood behind the wooden wall and could observe the throwing of knives through a peephole. The result of Stach’s performance was a punctured aluminum brooch, which the viewer was then able to buy and wear. In the case of this performance, the boundary and formal separation between the exhibited artwork and viewer/wearer was abolished, as was the line between the viewer and the author. The pierced brooch creates an emotionality frequently encountered in keepsakes that have lost their original beauty and function, but that still remain in our homes because of their emotional value.

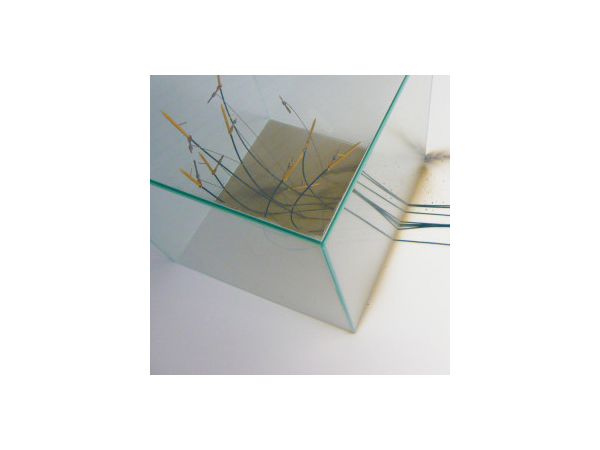

Another example of jewelry as performance is the work Space Race, by the Slovak jeweler Pavol Prekop. Prekop examines the boundary between jewelry as a material object and its potential to become a game and an experience for the viewer/wearer. The work, exhibited at Hot Dock Gallery in Bratislava, presented the audience with brooches in the shape of rockets with fuses. These rocket brooches were in a glass showcase, with matches placed next to it. The installation was intended as a dialogue with the spectator, who was encouraged by the artist to take action and ignite one of the cords sticking out from under the showcase and thus become part of the work. The performativity of the work created tension between what is visible and what is possible. Space Race is part of author’s larger project, Bleskové šperky (Flash Jewelry) and was accompanied during the exhibition by a short film and an audio story presenting the theme of flash jewelry through fictional stories.[2]

The Portuguese jeweler Carla Castiajo often deals with a material that has been repeatedly used in art and jewelry for centuries and has strong cultural significance—hair. During her pedagogical stay at Beaconhouse National University in Pakistan, the artist created a project titled Black Diamond that worked with rickshaws, one of the popular modes of transport in that country. She exchanged the back part of a rickshaw, which is mostly richly decorated, for a curtain of long black hair. The artist created an event in a public space, documented by a video which aimed to investigate the reactions to a material that hides both beauty and unease and provokes different cultural readings, reactions, and impressions.[3] Even though the work cannot be considered wearable jewelry, it refers to the art medium in the context of the artist and opens up the dichotomy between the formal and the material, the visible and the intangible in jewelry.

The common feature of the works described above is their aim to disturb and abolish the boundaries between object and subject and between author and audience, and to create critical situations that expose jewelry as an art medium to a broader interpretation and perception. Performativity as performance and event bring authenticity of time and active communication to the field of author jewelry based not only on visual perception, but rather on sensual experiencing and interaction.

Although these works open and challenge the conventional perceptions of form and material, they remain as an alternative jewelry practice to the works exhibited in galleries. There seems to be a missing link of institutional and theoretical support that would present these works to a specialized and lay public and further identify them. Will the “performative” in jewelry be able to carry on without theoretical and institutional reinforcement and background? How are these works understood beyond the “jewelry world”? Where is their place in the current art system, and what comes next?

[1] On the elementary power of jewellery oder Schmuck als Urgewalt: Eine mediale Rauminstallation von Gisbert Stach mit Videoarbeiten von Pavol Prekop/Jana Minarikova (SK) und Gisbert Stach (D). MaximiliansForum (online). Munich: MaximiliansForum, 2015 (cit. 2017-06-01). http://www.maximiliansforum.de/en/de/archive/archiv-detail/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=178&cHash=c70c9c3c3bab16462eb7405b434a58c8.

[2] Mýtus bleskových šperkov vedie k posadnutosti. Pravda: Kultúra (online). Bratislava: Martina Šimoňáková, 2015 (cit. 2017-06-01). https://kultura.pravda.sk/galeria/clanok/343797-mytus-bleskovych-sperkov-vedie-k-posadnutosti/.

[3] Carla Castiajo, Purity or Promiscuity? Exploring Hair as a Raw Material in Jewellery and Art (online). PDF. Tallinn: Estonian Academy of Arts, 2016 (cit. 2017-06-01). https://carlacastiajo.files.wordpress.com/2017/01/purity-or-promiscuity-exploring-hair-as-a-raw-material-in-jewellery-and-art5.pdf.