Jewelry made of glass can be mesmerizing. The pieces capture light and appear to make it move. They embody a full range of spectacular colors, or no color at all. They are precarious, because they carry the possibility of shattering. And they are made with fire, requiring precision, athleticism, and finesse.

Many jewelry artists who work with glass have honed their craft at The Studio at the Corning Museum of Glass, an artistic and educational glassworking facility that offers five-week, all-expenses-paid residencies for artists to immerse themselves in their work without the distractions of everyday life. Since the program began in 1996, about 10 percent of the artists have been jewelers.

Five of those artists—all living in the US—share their vision below.

DONALD FRIEDLICH

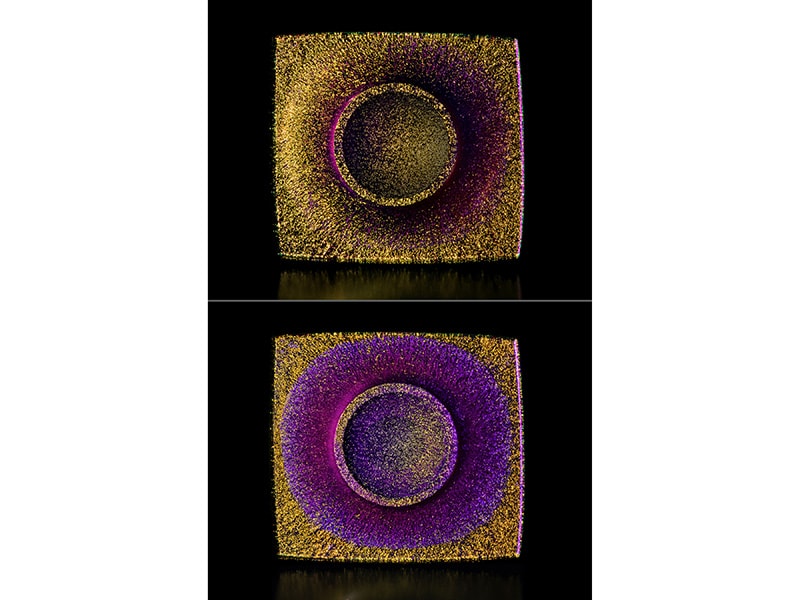

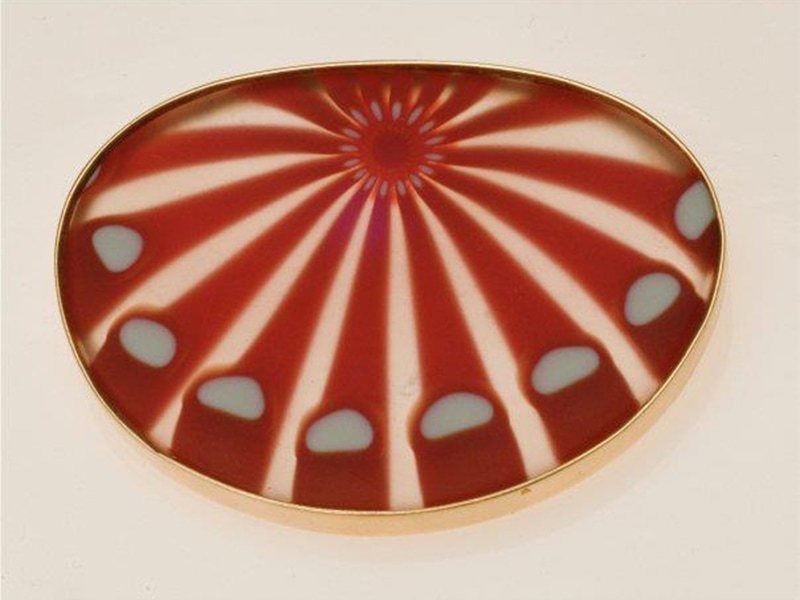

The glass brooches and pendants in Donald Friedlich’s Lumina series seem to change color as the wearer moves. They are inspired in part by the color field paintings of Mark Rothko and the light sculptures of James Turrell. The pieces shimmer as they shift from magenta to ochre, from deep pink to electric blue. Some resemble internally lit neon tubes, others evoke a total solar eclipse. “With most art glass, you are essentially sculpting light and color,” says Friedlich. “I wanted to create pieces that would dramatically change when viewed at different angles.”

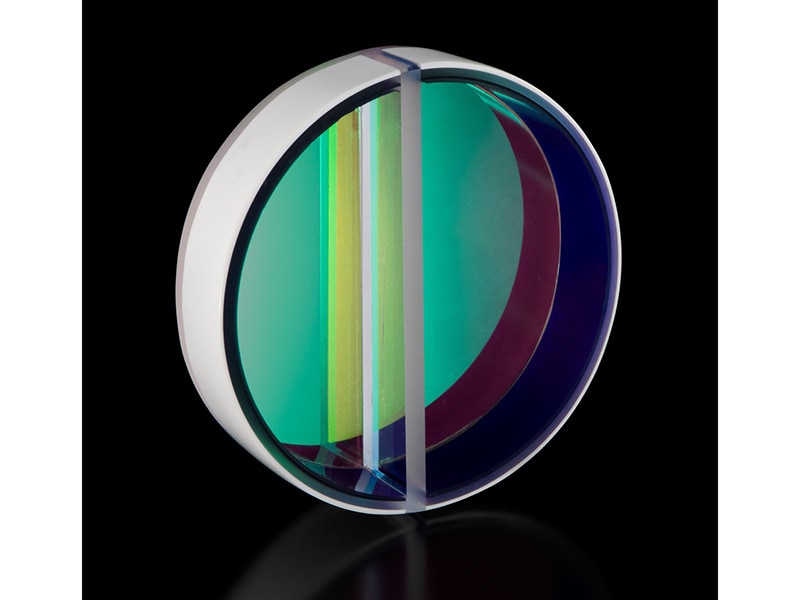

Friedlich, who is based in Madison, WI, knows the rules of glass, but he is also willing to break them. He has used a circle or square of Pyrex glass, which has a high melting point and is easier to customize for his needs than other materials, as a tool. He slumps another type of glass over the Pyrex in a kiln, with the knowledge that if the two incompatible glasses stick to each other, they will both crack. The work that results has a celestial feeling, recalling images from the James Webb Space Telescope. This effect comes from using a special coating called dichroic glass.

Friedlich had dabbled in glass as far back as college, but it became a major focus of his work in the late 1990s. Looking to expand what he could do with glass, he applied to Corning, and in 2003, became the first jeweler to be selected as an artist-in-residence. His collaboration with glassblower DH McNabb and master engraver Max Erlacher helped him bring a new palette of shapes and colors into his work, which took it in a new direction. “The residency was the most productive month of my artistic career,” he says.

He has brought humor to his jewelry with a series on food. Glass brooches take the shape of a stalk of celery (in orange, yellow, or blue) and a piece of asparagus (blue or purple). He says, “By casting these mundane materials in glass, I am hoping that the viewer will see them in a new light and realize what beautiful forms they are.”

PENELOPE RAKOV

The first thing that attracted Penelope Rakov to glass was the colors. “The range and brightness of the colors—it’s just magical,” she says. “The way the light plays through the color is fascinating to me.” Rakov started her artistic practice in college working with ceramics and glass.

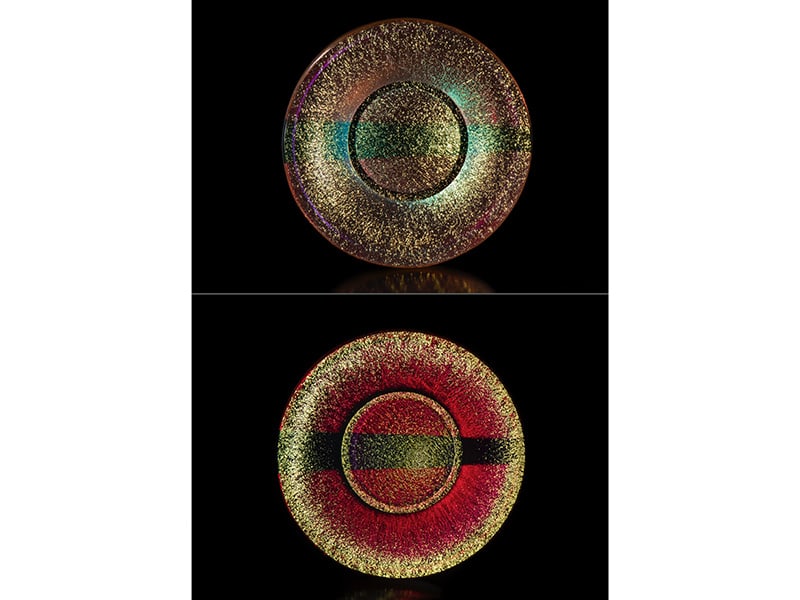

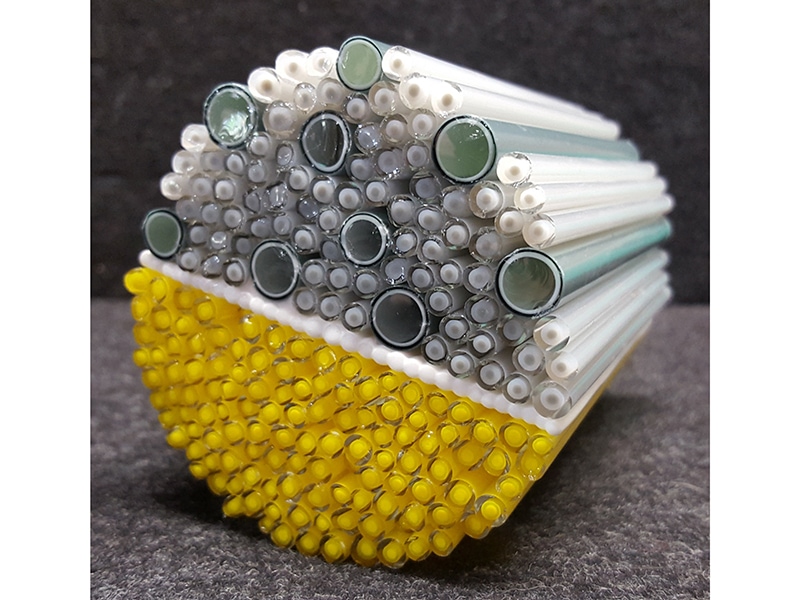

Then Rakov learned about murrini glass, and it became “an obsession” in grad school. Murrini are colored patterns made with glass cane—long, thin rods of glass—that are sliced, often into thin disks so that the intricate patterns are visible.

Making murrini starts with a chunk of colored glass heating up in the kiln. Rakov lines up several of those chunks and an assistant drops layers of color on top, so the colors are sandwiched together. Then that glass is stretched until it is 30 to 40 feet long, or the diameter of a pencil. Once it cools and hardens, she cuts it into pieces the length of a golf pencil. To make complex patterns, canes are heated, bundled together, and stretched again, sometimes several times. Finally, Rakov cuts through a bundle of canes to produce the thin slices that make up her necklaces, rings, and earrings. “It’s infinite retelling,” says the artist, who is based in Syracuse, NY.

The intricate patterns of her pendant necklaces feature colors from chartreuse and turquoise to deep red and black. Tiny disk earrings and larger dangles play with circles, dots, and amoeba-like shapes.

After her 2018 residency, Rakov was asked to make a video[1] of her glass technique, which she found nerve-wracking: “Glass has this showmanship to it,” she says, but it also holds the prospect of failing spectacularly. “I’ve picked up bundles that were too cold and they shattered—that’s hours of work gone.” Yet working with glass is “very meditative,” she says. “It’s the most relaxing thing I can think of to do.”

ERICA ROSENFELD

Erica Rosenfeld first made jewelry as a young girl, when her mother took her to the iconic Manhattan store M&J Trimming for beads to string on her safety-pin bracelets. She started working with glass in her 20s. Today, she makes murrini glass jewelry as well as sculptures and installations that use glass, performance, and found objects.

“I’m drawn to the physicality of working with glass,” Rosenfeld says. “It’s labor-intensive, with a lot of repetition of motion, but I love the ritual of it.” During her Corning residencies in 2010 and 2022, Rosenfeld made murrini in increasingly complex patterns. After slicing the canes, she sands the slices and gives them a matte finish, which she finds “more tactile than shiny glass.” For her necklaces, she sews the slices together with fishing line, with tiny beads between the murrini slices. Her designs are inspired by turn-of-the-century Viennese design and mid-century modern design.

Her artistic practice is rooted in her home, an 1899 brownstone in Brooklyn with original wood floors and a tin ceiling in the kitchen. She calls the light-filled room facing the garden the “shrine room.” It is filled with thousands of objects, from toys to plastic forks to saltshakers, arranged in various tableaux, as well as wallpaper and sculptures she designed. “To me, my real art is my home,” she says. “I love transforming a space, whether it’s in a room or on the body.” She also uses glass in many other projects, such as eggshell sculptures, glass sculptures that depict clouds, and installations that combine glass, painting, found objects, and other media.

As a member of an artist collective called Burnt Asphalt Family Performances, Rosenfeld participates in wildly inventive theatrical events where glassblowing and cooking come together.

Audiences watch as Italian meat or marshmallows or caramelized apples are cooked in a glass hot shop in spectacular fashion and then served to them in a hybrid of performance art, interactive installation, and dinner party.

LAUREN KALMAN

Lauren Kalman’s art practice investigates the history of adornment, body image, and beauty through performances and objects made of glass and other materials. After training as a jeweler, Kalman “made a move from jewelry as the form of my work to jewelry and adornment as the subject of my work,” she has explained. For several projects, she has created devices worn on the body as though they are jewelry, in order to explore the female body and expectations around what it is to be feminine.

Kalman, who is based in Detroit, was selected in 2020 for the inaugural Burke Residency, which is awarded by Corning and the Museum of Arts and Design, in New York City, to an artist under the age of 45. While at Corning, she used plaster casts of her torso, elbows, knees, and other body parts to create 45 vessels with glassblowers Ross Delano and Darin Denison that used the imprints from her body, for a project titled To Hold…

“Seeing the imprint of the body makes you think about the desire to hold on and hold close,” says Kalman, who was drawn to working with glass because it is a domestic object we interact with every day. “The wonderful thing about glass is its transparency and its familiarity. Even if you can’t touch the material in the gallery space, you understand what glass feels like.”

Experimenting with glass during her Corning residency, she says, “was like walking into uncertainty, and I think as an artist that’s a really healthy place to be.”

BIBA SCHUTZ

Biba Schutz has found glass fascinating since she visited Atlantic City as a child and saw lamp-working artists on the boardwalk making animal shapes. “I’ve always been mesmerized by glass as a material and its process,” she says. The self-taught jeweler is known for her work with metals, creating striking pieces in oxidized silver, copper, bronze, and gold inspired by her urban environment, New York City. Decades into her jewelry career, she decided to experiment with glass.

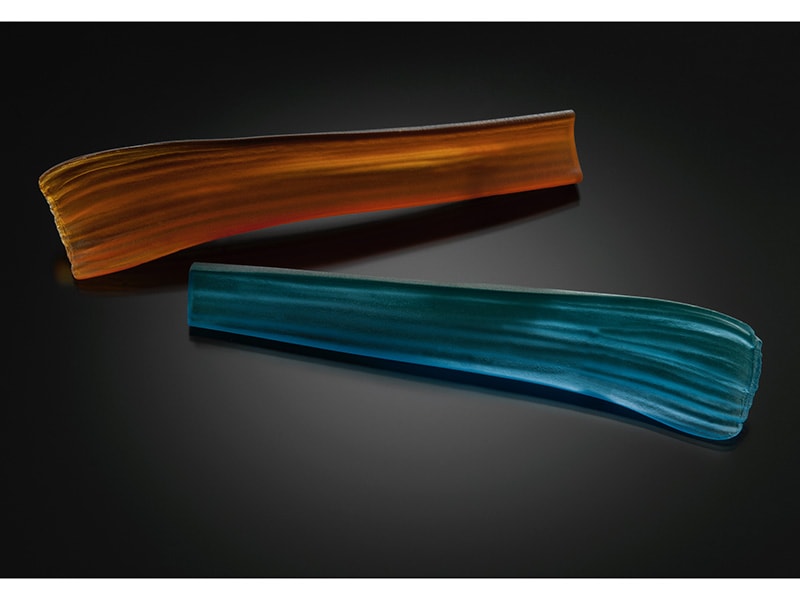

colored borosilicate glasses, blown, sandblasted, 7 ⅞ x 7 ⅞

x 1⅛ inches (200 x 200 x 30 mm), photo: Ron Boszko

Her 2014 residency at Corning was transformative. “I discovered my language for glass,” she says. She was paired with a glass blower, and the two created deformed globes of glass that Schutz adored for their mystery. “When I cut into the piece, I had no idea what I would find inside,” she says. The tunnels and folds she discovers within the glass become the pathways that she finds central to her work. Schutz also likes to leave an opening in the back of every piece of glass jewelry. “You can travel through the work, and there’s always a place to hide,” she says.

Her brooches, necklaces, and rings are blown borosilicate glass in numerous colors, with some of the most commanding pieces in green, white, black, and mirrored silver, mounted on sterling silver. Their shapes are graceful and intricate, from her “black corsage” brooch, which is a pair of swirling black forms, to a mirrored ring mounted on an oxidized sterling silver setting and shank, with a creamy white shape that evokes a cloud.

“Working in glass after all these years was taking a risk,” she says. During her residency, “we had a lot of failures, and I learned from all of them, which was an amazing gift.”

constructed and blown lamp glass, 3.75 x 2.9 x 1.5 inches (95 x 73.6 x 38 mm), photo: Ron Boszko

Corning provides a food stipend, an apartment, materials, equipment, and skilled support staff to assist the artists during their residencies, which are awarded to about a dozen people a year. “People really get to experiment here,” says Amy Schwartz, the director of The Studio. “They explore avenues they have thought about but weren’t able to realize.”

Note: Click here for information on applying for the Corning residency.

© 2023 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] Watch the video here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lWIm0YuhkkQ.