Kumi Kaguraoka, a Japanese artist based in Tokyo, makes wearable pieces inspired by anatomy, beauty standards across cultures and time, and the imagined concerns of a future humanity faced with environmental and societal shifts.

- She wonders why we continually pursue ever-shifting, painful, and hard-to-maintain beauty ideals

- Her artwork plays with the idea of altering the body’s shape and form through quasi-mechanical devices

- The works reference the overlapping history of humanity’s collective flesh and the never-ending desire to control and alter its physique via the shifting mythology of beauty

This is the fourth article in a series focused on artists whose work is adjacent to jewelry. For my purposes, jewelry-adjacent artists use material, techniques, or themes related to jewelry practices. The body is present in their work, not necessarily as the recipient of adornment, but in the importance of the physical body to their form, topic, or narrative. The adjacency of these artists to jewelry provides fresh perspectives to those of us immersed in the field.

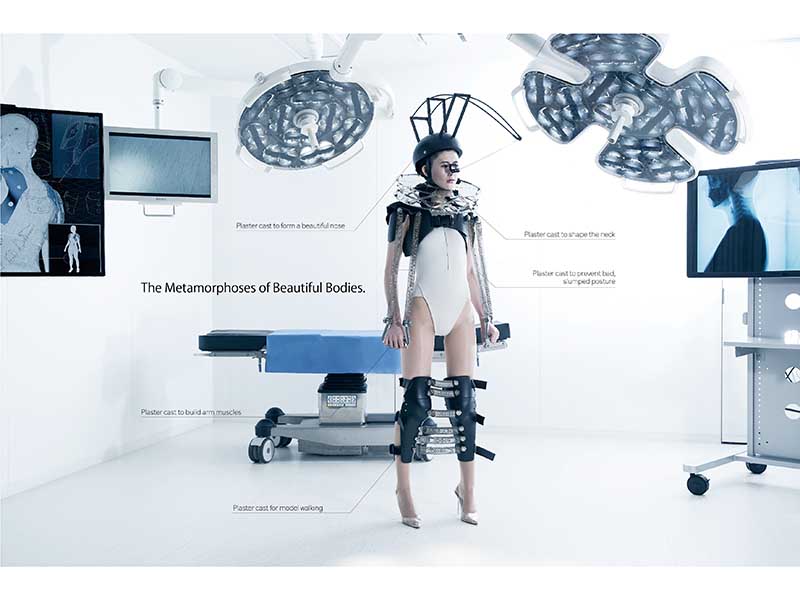

The culturally shifting ideals of beauty associated with the not-always-accommodating physical body provide Japanese artist Kumi Kaguraoka[1] with a generative place to consider the evolution of beauty standards. She uses non-traditional jewelry materials such as silicone, stainless steel, and 3D-printed nylon resin—selected for their durability—to construct her wearable artworks. Her pieces emphasize conceptual alterations of human anatomy inspired by current and past beauty standards across cultures. Through her work, she imagines the aesthetic concerns of future cultures faced with environmental and societal shifts.

With two parents in the medical profession, Kaguraoka grew up surrounded by medical books. At an early age, she attended the 1995 Body Worlds exhibition in Tokyo. Presented by Dr. Gunther von Hagens, a professor of anatomy, the traveling exhibition includes real human bodies treated with a patented plastination technique he developed as a preservation method more stable than embalming. The exhibits show numerous human cadavers posed to reveal the interior mechanisms of the body.

This exposure to the unmitigated reality of human anatomy played a role in Kaguraoka’s thinking, especially when coupled with anime, another early influence for her. Japanese animation, known as anime, features “the use of limited animation, flat expression, the suspension of time, … the presence of historical figures, [a] complex narrative line and, above all, a peculiar drawing style.”[2] The starkness of the human body Kaguraoka was exposed to in the Body Worlds exhibition contradicts the stylized representation of the human form in anime.

Anime characters reflect Western beauty conventions. Sailor Moon, with her iconic long blond hair, wide eyes, and legs that extended past any bodily authenticity, was a favorite character of Kaguraoka’s. As an artist now looking back, she is disturbed by the influence the Westernized features of anime characters had on Japanese identity as a result of the United States’s post-war occupation of Japan from 1945–1952. This discomfort drives Kaguraoka’s research of beauty ideals across culture and time.

“… the anime characters I admired as a kid have small faces, tall and slender bodies, blond hair, and big eyes. However, as I researched several fashion trends, folk costumes, cultures, and religions, I found that various body shapes were set as the ‘ideal.’ Where does this aesthetic value come from, and where is it going in the future?”

—Kumi Kaguraoka[3]

Kaguraoka found that since World War II, Japanese people have subscribed to American and European ideals seen not only in anime, but in movies, TV shows, and other media, such as fashion magazines. She notes that plastic surgery is on the rise in both Japanese men and women from a very early age as they change their faces to meet Westernized beauty ideals, such as narrow noses, wide-open eyes, or impossibly thin figures.

Kaguraoka’s visual influences go beyond the physical and animated body. She spent four years assisting Asao Tokolo,[4] an interdisciplinary artist whose work crosses between mathematics, architecture, design, fashion, and art. Kaguraoka also designed paper clothing, specifically costumes for stage production, solving disconnects between real bodies and idealized costumes. She briefly became a toy designer. In that role she focused on creating prototypes, building toy exhibition spaces, and designing other toy-related goods. However, she found the building of toys and packaging stifling, constrained by design parameters and toy functionality. Through this job, however, she learned about 2D and 3D software which she applies to her wearable artwork today.

“I have a strong desire to create work that expresses the themes that make life difficult and question human society through the body. I want to live honestly with myself.”

–Kumi Kaguraoka[5]

In March 2022, Kaguraoka came to New York as an artist-in-residence at The New York Art Residency and Studios Foundation.[6] Through this international residency program, she is conducting research on aesthetic differences across cultures. When she arrived, she was surprised to see a disconnect between how most American women looked compared to what is seen, for example, in films. Even the American mannequins were full-figured and there are more plus-size models, both on the runways and on magazine covers. This was different from her experience in Japan, where department store mannequins displayed supermodel physiques, divorced from the reality of the typical body type of Japanese consumers.

Between the constantly shifting and overlapping cultural landscapes and new technologies changing today’s fashion standards, Kaguraoka considers what beauty may be in the future.

Her artwork plays with the idea of altering the body’s shape and form through the intervention of quasi-mechanical devices. She views her work as a “cynical expression of the contradictory state of blind pursuit of beauty by humanity.”[7] Why does humanity choose to pursue painful, difficult-to-maintain, and even harmful beauty ideals? Why do we keep changing the self-imposed definition of beauty? She wonders if within this paradoxical questioning lies the definition of what it is to be human.

Kaguraoka sees her project as gender-neutral but also reaching across cultures and time since beauty ideals affect all people. Her professors at Musashino Art University, where she received her MFA in scenography, display and fashion design in 2012, encouraged her to expand her line of research outside of current fashion and beauty trends. Cultural anthropology, human evolution, and the many facets of aesthetic history, from fashion to design to science, all inform her research. Through reading academic papers, interviewing anthropologists from Japan, and visiting museums with collections that reference the many ways beauty takes shape in the world, Kaguraoka’s work incorporates past beauty standards and projects her curiosity about beauty into a shared future.

“Body is something that everyone can have and share. And it can be approached not only from art but also from aspects such as design, science, history, and culture. [Kaguraoka] has been persistently planning and researching and seeking new creations that present a vision to society. She has been conducting research on concepts, materials, and methods of production, and has been discussing with specialists in various fields such as fashion and folklore, not only art.”

—Junya Yamamine, curator, Tokyo Art Acceleration/Director, ANB Tokyo

For example, in her research, Kaguraoka found that at different times in history and across different cultures, a tall, elongated skull was considered more beautiful. People in France, Egypt, and regions of South America manipulated the soft heads of newborns to achieve that appearance. Similarly, other body-focused practices such as foot binding, which causes permanent alteration, or the wearing of high-heeled shoes happened in different cultures across time. The one thing that remains relevant, at least to Kaguraoka, is that humans have altered our bodies in the past, we continue to alter our bodies today, and we will most certainly alter our bodies in the future.

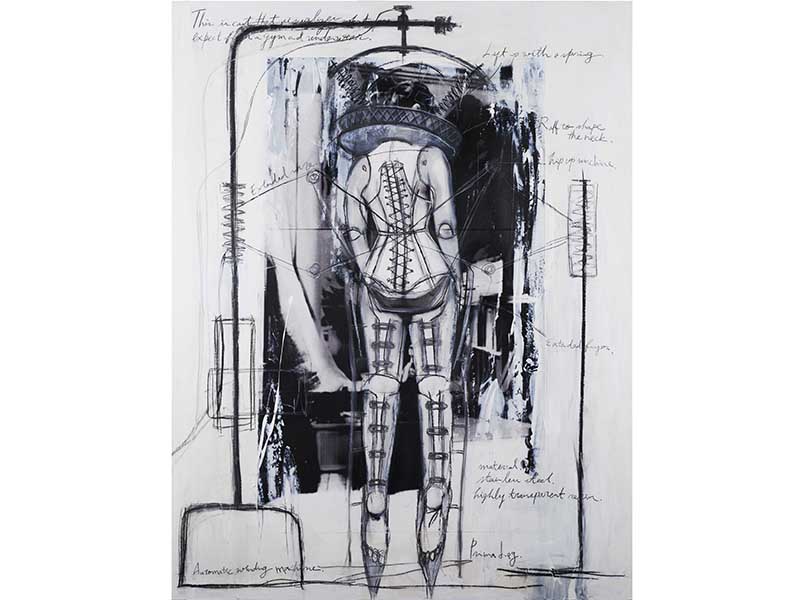

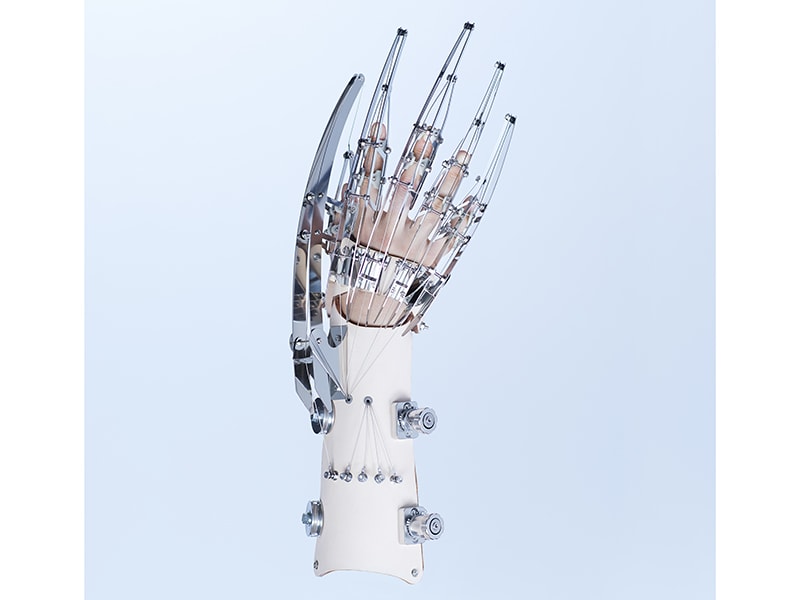

Perhaps future aesthetics will be driven by changes in the environment, forcing the reassessment of aesthetic culture and value as related to shifts in clothing, food, and shelter. Kaguraoka’s artwork utilizes the body as a site for imagining these future alterations, but before she begins to build, she draws. The process begins with a question, inspired by her research–will elongated fingers be beautiful in the future? Then, she illustrates a hand with extended bones in the fingers, the flesh and bones surrounded by mechanisms to instigate the desired structural changes. Detailed measurements, radial lines showing direction, and explanatory text fill the page. The drawings act as blueprints, plans for creating the prototype. They act as an eerie record of the exacting specifications placed on the human form. Kaguraoka also utilizes altered X-rays to envision the skeletal alterations the artwork will bring to the body.

The final pieces are clean, mechanical, and severe in their design. The textural beauty of Elizabethan ruffs[8] and the richness and depth of Padaung brass neck rings[9] are clear inspirations for Kaguraoka’s Ruff to Shape the Neck, but her iteration utilizes futuristic, stainless-steel expanding circular disks to elongate the neck. The austerity of the material makes it difficult not to see torture devices in these pieces, though they may be aesthetically pleasing, thoughtfully balanced, and beautifully photographed. Kaguraoka includes large-scale, full color photographs in her exhibitions to help the viewer make the connection between these metal, leather, and plastic contraptions and their intended effect. The body is necessary to understand these pieces. However, they seem familiar—the shoulders feel the weight, the fingers flex, the legs ache—so clearly do they reference the overlapping history of humanity’s collective flesh and the never-ending desire to control and alter its physical reality via the shifting mythology of beauty.

[1] http://www.kumi-kaguraoka.com/.

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anime.

[3] From the artist statement on DesignBoom, August 11, 2022.

[4] https://www.japanhouselondon.uk/discover/tokolo/.

[5] From a conversation with the artist, September 9, 2022.

[6] https://www.narsfoundation.org/kumi-kaguraoka-japan.

[7] From the artist’s statement.

[8] https://historicalbritain.org/2013/07/22/elizabethan-ruffs/.

[9] National Geographic Video, “Why Do These Women Stretch Their Necks?” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0FME1At3vmI.