- Jewelry maker Meaghan McRae feels pressure to keep her rock ’n’ roll and traditional Indigenous styles separate

- Galleries are concerned that buyers, often tourists, have a specific idea of how Indigenous art jewelry should look

- But rock ’n’ roll and Indigenous identities have always gone together

- Politely, defiantly, McRae is starting to merge her designs, and buyers are receptive

Meaghan McRae, exhausted after a long day in her jewelry studio, relented. She would start a second Instagram account. For nearly a decade, she had built her Lunden Jewellery (@lundenjewellery) account with daily posts showing her work, educating followers about her process, and revealing her inspiration. She enjoys sharing with her fans. But social media adds hours to studio time while taking away from actual jewelry making. Now she’ll spend time on a second account because the art jewelry world doesn’t always see McRae’s two identities—rock ’n’ roll and Indigenous—as belonging together. McRae is working to change this by teaching people the value of buying jewelry that brings tradition together with an artist’s unique expression.

Right now, however, McRae feels pressure to keep her rock ’n’ roll and traditional Indigenous styles separate, at least until she’s more established. She needs to make rent, and the galleries that sell Indigenous art often only want the traditional designs. While she’s urging a shift, McRae understands: galleries also need to sell and they’re concerned that buyers, often tourists, have a specific idea of what Indigenous art jewelry in the Pacific Northwest looks like. Skulls and daggers, they worry, aren’t what people will buy. So they’re reluctant to link to her @lundenjewellery account, where the rock ’n’ roll pieces were posted next to the traditional Indigenous designs. That’s why she also runs @fireweedcarving, paying homage to her lineage in the Fireweed Clan. “Now that it’s separate,” McRae says, “it seems to put everyone at ease.”

But rock ’n’ roll and Indigenous identities have always gone together. As matt lambert covers in the AJF series Indigenous &, Indigenous identities intersect with the many dimensions of a person: their body, experiences, and ideas. “It is impossible to separate them from each other,” lambert notes. The designs of the jewelers who identify as Indigenous interviewed in that series are as varied as Indigenous communities themselves. The organic and natural, the modern and technological, the accessible and luxurious are all part of Indigenous jewelry.[1] There are traditions that Indigenous jewelers learn from, celebrate, and build on, but there’s no one style of Indigenous art jewelry. And techniques developed in Indigenous communities have long been taken, used by, and influenced the whole art jewelry world—just as many foundations of rock ’n’ roll come from the music in Indigenous communities and some of the most famous and influential musicians in rock music, such as Link Wray, are Indigenous.[2]

McRae is a member of the Gitxsan First Nation in northwestern British Columbia. She loves carving (engraving) the formline (shapes and lines) of the traditional animal designs of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. “When you see a whole bunch of bracelets in the store, at first they can all look alike, but when you learn about the history, tradition, regional differences, and how the shapes go together, it creates this structure that you have to build within that is really challenging,” McRae says. “It was way more complex than I even knew.”

While doing contract work, McRae started her first line of jewelry. She was advised to make simple dainty pieces that could sell at low price points, nothing challenging. “People-pleasing, crowd-pleasing jewelry,” she says. “I wasn’t jazzed about it at all. It had nothing to do with me.” And without having a connection with the work she made merely to sell, the jewelry didn’t ultimately land with buyers. “I was playing it safe.” She kept doing contract work.

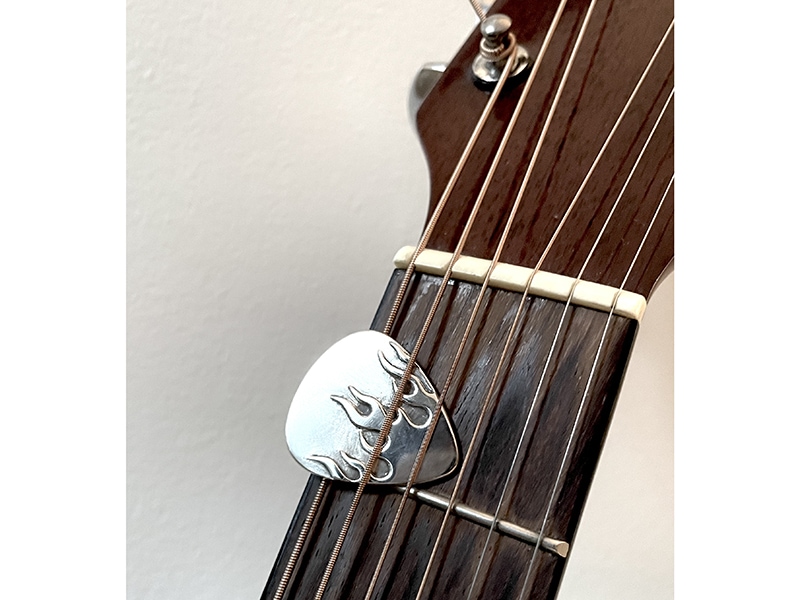

Then the pandemic hit. As the weeks went by and everything seemed to be falling apart, she said, “Fuck this. I’m going to make the stuff that I want to make.” She started by designing a collection based on the Dutch vanitas still-life paintings that portrayed vases of flowers along with rotting apples, burning candles, and skulls. The message: “Life is fleeting and you’re gonna die, so go do something.” She added elements to her designs, drawing from classic tattoos, old pin-up images, DIY punk, and the jewelry worn by famous rockers. Thus started her rock ’n’ roll jewelry: pendants with daggers, flaming hearts, and IUDs, and rings with skulls, hot lips, and wild roses.

These pieces are based on the fierce and determined approach to life in the music and subcultures that she loves. Some of these symbols—skulls and daggers, for example—have become cheap, mass-produced, widely available at shopping malls. McRae wanted to take the designs back to a slow, careful, detailed, even tedious production, by hand, by herself. Like her best-selling middle finger pendant, it was a “fuck this” to what she should do and an embrace of what she wanted—needed—to do. “I want to make jewelry and I want to make my jewelry,” she emphasizes. “I want my actual personality on display. Even though all of this shitty stuff was going on in the world and I didn’t know where money was coming from, I was just so stoked to be carving these mini sculptures that were finally an expression of me.”

McRae has also kept a focus on the traditional Indigenous designs that mean so much to her: “I can’t imagine not doing either one.” She sees a clear commonality in her rock ’n’ roll work and in her Indigenous designs: “They both have a warrior vibe, making you feel powerful when you wear the jewelry.” She makes big, bold shapes using traditional elements, “pushing the bold,” as she puts it. She wants all of her pieces to be legible and “visually demanding” even from far away. The traditional art from her village was meant to be intimidating. “The animals,” McRae says, “they’re hardcore. They aren’t just beautiful. They could kill you. You aren’t bigger, better, stronger than them. We think we can take over the planet. They’re there to put us in our place. I like that vibe.”

Recently McRae participated in an Indigenous Artisan Market at an Indigenous art gallery. She took her pieces with traditional Indigenous designs as well as a few of the rock ’n’ roll ones. Buyers were really receptive to both. “I could have brought them all,” she said. “They ended up loving it. People are super welcoming.” And she learned from other Indigenous artisans who were there that skulls and daggers are traditionally part of Indigenous symbolism in the Pacific Northwest.

Politely, defiantly, McRae is now starting to merge her designs, placing traditional Indigenous carvings on her larger rock ’n’ roll pieces and making jewelry that is uniquely her. She says, “I hope to be part of a wave of artists pushing galleries and individuals to buy jewelry that is both strong in tradition and has room for the jewelry artist’s own voice.” She adds, “My voice as an artist is bold Indigenous jewelry. The kind of pieces that make the viewer say ‘that’s fuckin’ badass, man.’ Just like hearing Link Wray’s ‘Rumble.’”

McRae and her work, process, and inspiration can be found at both @lundenjewellery and @fireweedcarving. “I always let people know that there are both accounts,” she says. “That they come together.”

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] See Indigenous &: Tradition Meets Technology—Pat Pruitt on Industrial Aesthetics and Referencing Traditional Ones and Indigenous &: Having Roots to Grow in New Directions—Elias Not Afraid on Beading as Luxury.

[2] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KFCpUZVyXgg. Also see the 2017 documentary, Rumble: The Indians Who Rocked The World directed by Catherine Bainbridge and co-directed by Alfonso Maiorana.