For jewelry artist Steven KP, collecting jewelry is often a way to celebrate their relationship with the piece’s maker.

Acquiring another artist’s work through a trade or a purchase is “an incredible moment of exchange. It’s appreciation and acknowledgment of the immense labor and care that goes into the object,” they say.

KP, who is based in Providence, RI, US, is known for their pendants and brooches carved from wood. These take the form of knots, ones that can never be unraveled.

“My work is a practice of care and tenderness,” KP says. “To carve wood, you have to spend time with it, learn how to love it, and listen to it.” Currently a visiting lecturer in jewelry and metalsmithing at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design, KP received the Marzee Graduate Prize in 2020. Their second solo show, Drifters, will be on view March 29–April 25, 2025, at Galerie Noel Guyomarc’h.

KP has another motivation for collecting: acquiring pieces that they want to share with their students. “Seeing work in images, through publications, or online is great, but it cannot compare to holding a piece of jewelry, studying how it has been made, and feeling it as a physical, real object,” KP says. “It completely changes a student’s relationship to the artist’s work and brings them into the same world as the piece.”

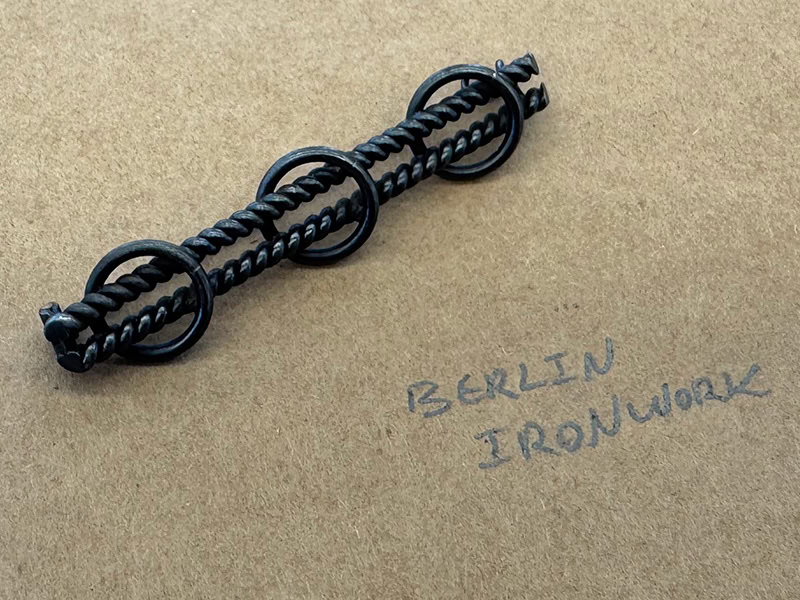

“This is the first serious piece I bought for myself, and one of my favorite objects,” KP says of the pin shown above. It was made in the 19th century as part of a fundraising campaign by the Prussian royal family called “I gave gold for iron.” Citizens were asked to donate gold jewelry to fund an uprising against Napoleon and were given a piece of jewelry made of iron in return.

OTHER ARTICLES IN THIS SERIES

A Peek into the Collection of Helen Britton

A Peek into the Collection of Tanya Crane

A Peek into the Collection of Atty Tantivit

“They were engineering marvels, but not worth anything materially,” KP explains. Wearing the piece demonstrated your support for the cause. The pin “is quite contemporary, and it was cast in a singular piece. There are no soldering seams,” KP says.

KP acquired the piece in 2017 while studying in Europe on a Windgate Fellowship, awarded by the Center for Craft in Asheville, NC, US. As part of the fellowship, they cleaned and repaired silver works of Judaica that were hundreds of years old.

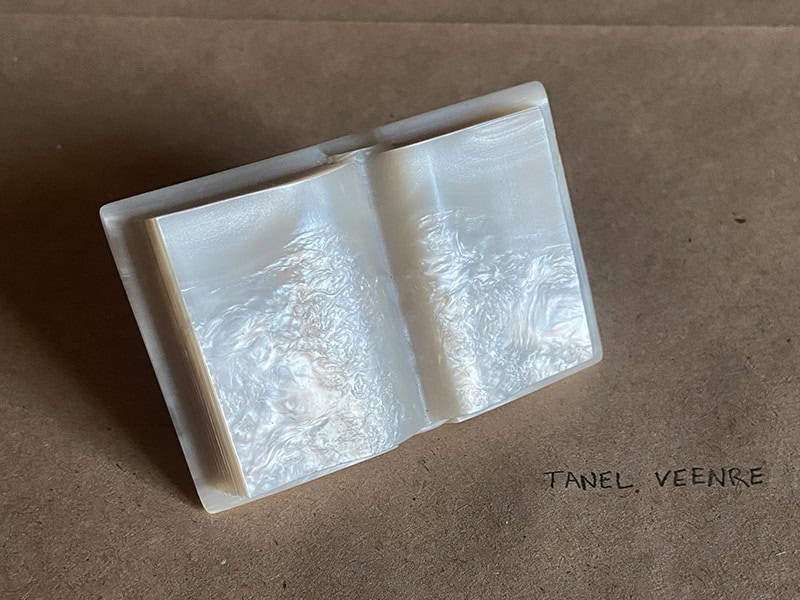

Carved from a reconstructed block of mother-of-pearl, the brooch shown above, by Tanel Veenre, takes the shape of a book. The title references a novel by the same name, written by Umberto Eco, that speaks to how we tell and remember stories. “I create to understand,” Veenre says. “It is a never-ending failure and always starting anew, as each solution gives way to another puzzle.”

KP served as Veenre’s assistant, at his studio in Tallinn, Estonia, while on a research and travel grant from the Rhode Island School of Design. At the time, KP was primarily working with metal, but “on my second day, Tanel gave me a piece of coral and said, ‘Carve this.’ And that was when I went back to carving.” The technique is now a central element of KP’s jewelry.

“This work is a particularly strange and, I think, beautiful example of Tanel’s hand-carved books,” KP says. “The pages have no writing, but they carry the narrative of the materials’ deconstruction and reconstruction.”

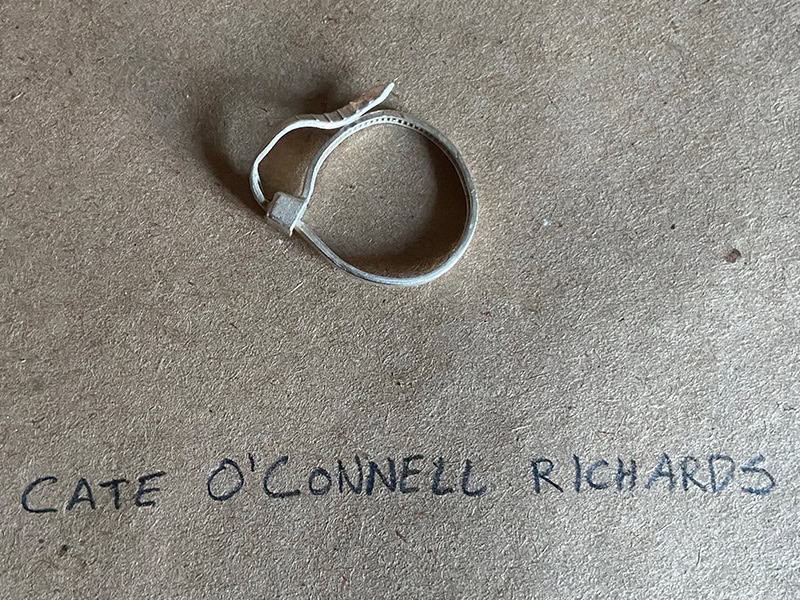

The ring shown above is a tiny, detailed replica of a zip tie, complete with a notched surface. Nylon zip ties fasten items together. They’re used once and discarded, but O’Connell-Richards “makes an heirloom out of it,” KP says. The artist, who is based in Madison, WI, US, centers much of their work on creating jewelry and other pieces that mimic familiar objects.

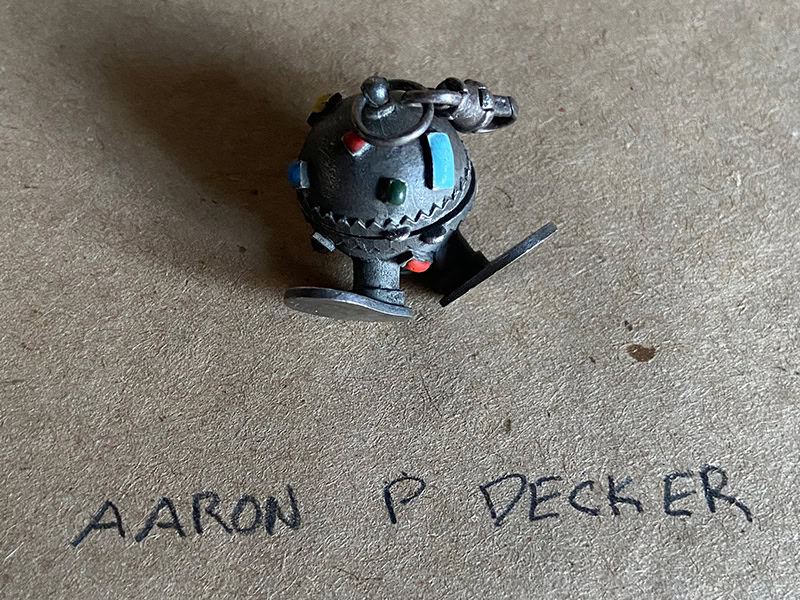

The little creature shown above, by Aaron Decker, is an oxidized sterling-silver locket with enameled “confetti” ornaments. Bomb Boy is a toy and a jewel that speaks to the playfulness and violence of childhood toy soldiers. It’s sentimental and charming, but carries with it the seriousness that comes with war. Reflecting on his childhood in a military family, Decker employs war imagery, such as metals and camouflage, to explore his queer identity.

Decker, who lives in Michigan, is close friends with KP. “We often talk on the phone or send each other photographs of works in progress. It’s simultaneously therapy and critique,” KP says. “If I’m really stuck on a piece, I just ship it to him and say, ‘What should I do here?’”

KP adores the work of another Estonian jewelry artist: Nils Hint. It was acquired from Gallery Loupe. The brooch is made from two Soviet-era steel cutlery knives, which Hint bifurcated and made to look like ribbons. Hint, who is based in Tallinn, transforms utensils and tools made of iron and steel into lightweight, wearable jewelry.

Estonia was occupied by the Soviet Union from 1944 to 1991. “What does it mean for an Estonian artist to reconstitute Russian material?” the piece asks, according to KP. “It’s a delicate gesture born out of necessity.”

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org