For close to 50 years, one of America’s first abstract sculptors playfully created unique bronze sculptures designed to wear as necklaces. Ibram Lassaw (1913–2003) was born in Egypt and arrived in New York as a child in 1921. His parents were listed as Ottoman Hebrews on the ship manifest but they had started their journey in Odessa. The family settled in Brooklyn, where Lassaw quickly adapted to his new home. From a child playing with clay near the seashore in Alexandria, he went on to become a well-known sculptor working with welded metals. In the early 1930s he met other artists, such as life-long friend Willem de Kooning, with whom he shared a love of music and the tricks of living in industrial lofts. He worked alongside Jackson Pollock for the Public Works of Art Project cleaning pigeon droppings off of city park statues. He met Buckminster Fuller at Romney Marie’s Artists Dinner Club in Greenwich Village, where they both were in need of her free meals. He was friends with poet Frank O’Hara, photographer Rudy Burckhardt, musician John Cage, and dancer Merce Cunningham. Joseph Campbell and Marcel Duchamp were close neighbors. Lassaw was an integral part of the downtown artists scene.

In the mid-1930s he was a member of the Artists Union, a group that protested for artists’ jobs; worked in the Works Project Administration, and with painter Alice Mason helped found the American Abstract Artists group in 1936. In 1944, after serving in the US army, he married Ernestine Blumberg (1913–2014) a painter and the coloring editor for Famous Funnies, the first comic book. Together they “homesteaded” a large light-filled loft on the corner of 6th Avenue and 12th Street, just across from the New School. They became my parents in 1945. In late 1949, Lassaw was a founding member of The Club, a loose affiliation of New York artists who gathered together to discuss art, philosophy, and other topics of common interest. The Club was at the heart of the development of Abstract Expressionism. Lassaw’s sculptures are in the collections of the Whitney Museum; the Museum of Modern Art; the Metropolitan Museum of Art; the Jewish Museum in New York; the Smithsonian; the Guggenheim Museum, Venice, Italy; the Albright-Knox; the Newark Museum; the Museum of Fine Arts, Montreal; the Baltimore Museum of Fine Arts; and many others.

Early years

As a young man in New York, Lassaw studied art history by going to museums and reading art magazines. He was impressed that the ancient Greeks and Egyptians, as well as other cultures, all painted their sculpture in bright colors. He studied sculpture with Dorothea Denslow at the Clay Club in Brooklyn and became proficient in the classical techniques of clay modeling, casting, and life/death masks. His imagination was set alight when he saw the International Exhibition of Modern Art assembled by the Societé Anonyme in 1926 at the Brooklyn Museum, with works by some of the leading avant-garde European artists. He realized that it was not necessary to repeat the art of the past, and that new materials and techniques allowed an artist to find original forms. He took his direction from science and philosophy. Along with his study of art history, Lassaw read avidly in the natural sciences and cosmology. He recognized early on what we now call systems theory, or the interconnection and interdependence of all living and material things. All of his sculpture reflects the truth of this interconnection, and it was also inherent in his drawings and bosom sculptures. He used to say “matter spirits,” meaning that everything is alive, and he believed that, as an artist, he was doing his unique part of the work of the cosmos. His natural path was set for him and he never wavered.

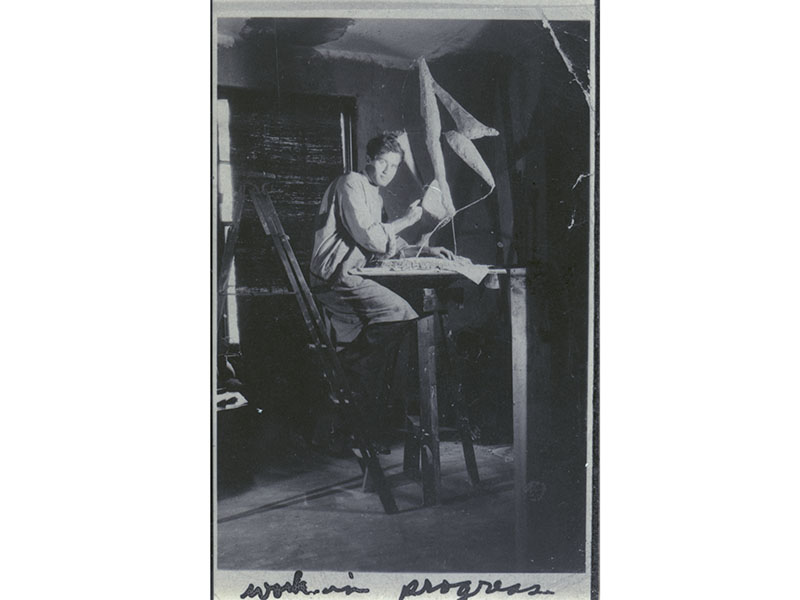

Lassaw was consumed by the desire to make sculpture that was not monolithic. His first abstract sculpture was made in 1933, of plaster and wire. He experimented with materials, but it wasn’t until he sold his first sculpture in 1951 that he was able to buy welding equipment, which enabled him to use metals that could be both very strong and open to space. He read about the nature of different metals and their colors. There was golden colored bronze, red copper sheet, dark red phosphor bronze, silicon bronze, a light pink, nickel silver, and steel for dull black. Sometime later he studied the use of acids that would turn copper green or blue.

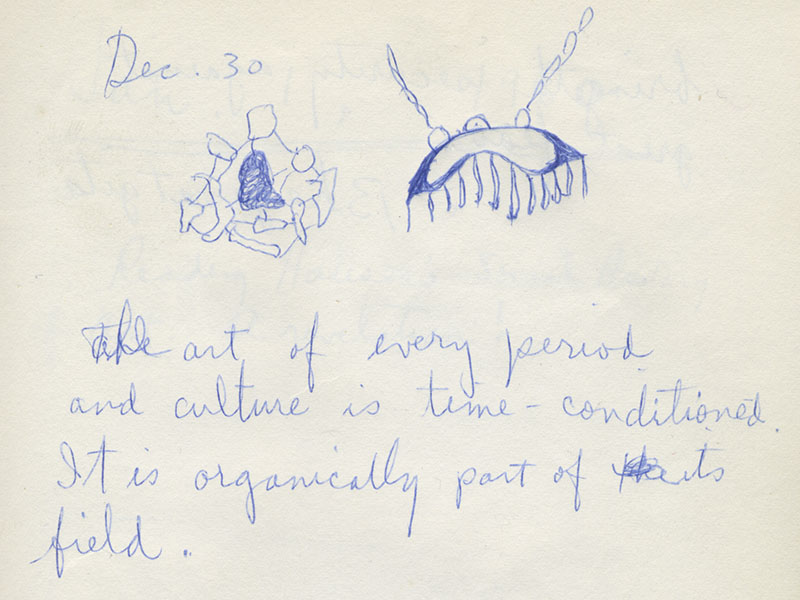

Lassaw’s sculpture continued to change over the years. The changes were influenced by the tools and materials that were available to him, and by his readings in philosophy, materials science, science fiction, biology, cosmology, travels, etc. He was influenced by all of life. Lassaw was interested in the textures of space, the shapes between solid forms, which included how things grow, the natural morphology of trees, plants, crystals, galaxies, and cells in the human body. All these have particular patterns that repeat across species and within their own phylum. For instance, a spruce tree, no matter its size, has branches that tend to hang down, to shed the weight of snow. Sunflowers have a spiral arrangement of seeds starting from the center. Galaxies also tend to have spiral patterns, at least from earths view. Rock crystals have square, pointed, or multisided geometric shapes, depending on their chemistry. So in creating a sculpture, a drawing, or a piece of jewelry, a particular morphology would suggest itself to him and he would investigate it. He never made drawings for sculptures. In his view, drawings, sculptures, or jewelry only represented themselves. He did not intend them to look like or stand for anything other than themselves. Some morphologies continued to be attractive to him for months, others only once. Some he abandoned and then returned to years later. He liked being surprised by his own work. It was an intimate hands-on feedback loop, each shape or texture suggesting where it wanted to go.

His first welded works were very delicate, just as his first pendant has none of the built-up bronze of later works. Pendants from the 50s and 60s are made from multiple metals and have small areas treated with acids. There are a few pendants that have a very similar shape to certain drawings, and I would guess that they were created around the same time.

Genesis of the bosom sculptures

In 1951, Samuel Kootz invited Lassaw to join his gallery in New York. He also had a summer gallery in Provincetown, MA. Lassaw had been summering in Provincetown since 1944, and in 1951 rented an apartment next door to the Kootz Gallery. Among the artists in the Kootz Gallery were Jean Arp, William Baziotes, Georges Braque, Jean Dubuffet, Herbert Ferber, Arshile Gorky, Adolph Gottlieb, David Hare, Hans Hofmann, Fernand Leger, Georges Mathieu, Joan Miró, Robert Motherwell, Pablo Picasso, Pierre Soulages, and Maurice de Vlaminck.

In a 1982 interview with art historian Nancy G. Heller, Lassaw tells how he began making pendants and selling them at the Kootz Gallery in Provincetown:

“We were spending the summer in Provincetown, it was 1951. I was working in a little shed that I rented, and I had bought several different metals—alloys, instead of just the brass color. I wanted to make a sort of swatch—you know, you try out colors, put on a dap of this, and then something next to it, and see how it looks. So I took some wire and made a kind of shape—roughly, quickly, just to try something out. Then I melted some brass, and a little phosphor bronze, and nickel silver, to see how it looked together. At the end of the day, I took it back to the house where we were living on Commercial Street, and I showed it to Jane and Sam Kootz, and Ernestine, who were all on the beach there, nearby. Ernestine put it to her breast and she said, “Well, you know, I could wear it!” and Sam Kootz said, “Oh, that looks interesting.” And then Jane Kootz said, “I want one of those.” So I made one for her, but a little bit more consciously, as something to wear. And then some woman who knew the Kootzes also wanted one, so I made another.”

In her PhD dissertation, The Sculpture of Ibram Lassaw (1982), Heller wrote, “Kootz first sold them for $50. Lassaw estimates that he had made roughly 23 pieces by November 1952 and some 1,200 by August 1979.”

In 1987, Lassaw said, “Since 1951 I estimate that I have made over 1,000 different pieces. I prefer to think of them as wearable sculpture. They reflect the general direction of my sculpture, being asymmetrical and irregular. Each piece is developed without making drawings or plans but welded directly in bronze. My primary interest is in the color and texture of the metal and the stones, and not so much in its intrinsic value.”

The first bosom sculptures were made mostly of bronze, with additions of other alloys for their colors. In later years Lassaw sometimes set semiprecious stones in a silver bezel, but some early pendants had little shells or quartz beach pebbles held by bronze prongs. Ernestine had a great eye for finding beautiful pebbles. However, her pebbles were the only found objects Lassaw used. He occasionally used odd-shaped semiprecious stones, but these were “found” at a gem store on Maiden Lane in lower Manhattan.

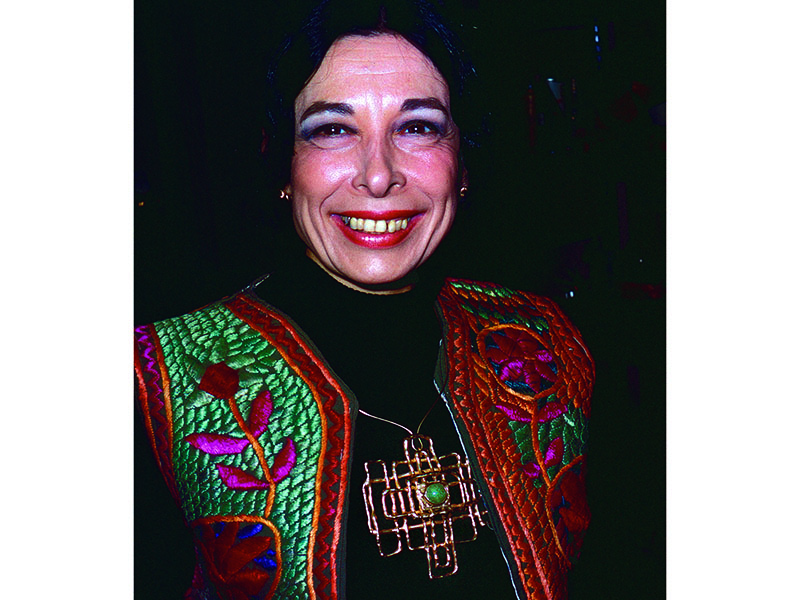

Until 1954, Lassaw made only pendants that hung on chains, but that summer he created his first necklace. We were living in Taos, NM, and Ernestine fell in love with Navajo silver and turquoise jewelry. Living next door to us was the sculptor David Hare and his wife Jacqueline Lamba, a painter who had been friends with Frida Kahlo and wore beautiful necklaces and clothes like hers. Both Ernestine and I were fascinated by Lamba. Together we camped around New Mexico and Arizona, staying in Canyon de Chelly, Ship Rock, and many other wild places that Hare already knew. Although Ernestine wanted a silver necklace, money was tight and our 1949 Ford Woody station wagon, which my father had bought from Max Ernst, was always breaking down, causing us to stay for days in small desert towns waiting for parts.

Since he couldn’t buy her what she wanted, my father made her a large necklace inspired by Navajo jewelry. It was composed of many small interlinked bronze chains topped with forms which might have been inspired by the squash blossom motif. She later wore this grand necklace to Museum of Modern Art openings, a dinner at Nelson Rockefeller’s penthouse with Alexander Calder, and a Halloween party at the artists Club. I also received my first necklace that summer.

Lassaw did not begin to sign his jewelry until 1963. Before 1963, his signature was in his very individual morphologies and techniques. His work was never symmetrical, never “designed.” It grew organically. Besides bosom sculptures, he made some belt buckles and a few bracelets, but only when asked. One or two collectors bought very small pendants and had them attached to plain ring bands, but Lassaw never made any rings or earrings.

When he made necklaces, he made an attached chain. Chains are tedious, but not difficult to make. Chains that are commercially available are rarely aesthetically satisfying and never seem to belong to the pendant they are attached to, so a handmade chain makes sense. Lassaw told me he enjoyed making pendants. For one thing, they were like tiny sculptures or quick sketches. Also, people were always asking for them. He gave away many to friends and studio visitors he took a fancy to. It was easier to sell a pendant than a sculpture, and I am sure pendants got him through times with no sculpture sales. He certainly did not get the kind of prices that are being asked on eBay or at auction today.

The pendants made of bronze alloys had one problem: Over time, they oxidized and turned dark. I used to shine them with a little fine steel wool or by rubbing them on my blue jeans. Sometime later, I used a cotton polishing wheel with white diamond rouge to achieve a bright shine, but for the collector who often had no knowledge of such things, it was a problem. The brightness of the metal was an important aspect of both sculpture and jewelry. Beginning in the mid-1970s, Lassaw began gold plating his jewelry. Gold never tarnishes. People loved the shiny gold, as it made the pendants very rich and unique. A woman traveling in India had her pendant stolen, and Lassaw gave her a new one because he had great respect for Indian art and philosophy and was flattered that his work was desirable to someone from that culture.

Exhibitions

Over the years, Lassaw pendants were shown in a number of museum exhibitions both in the US and in other countries. From 1953 until 2020, his work was in at least 30 shows, including:

1961 International Exhibition of Modern Jewelry 1890–1961, organized by the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths in association with the Victoria and Albert Museum, London

1967 Exhibition of Jewelry by Painters and Sculptors, organized for circulation by MoMA

1973 Jewelry as Sculpture as Jewelry, at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston

2006 Objects of Desire: 500 Years of Jewelry, Newark Museum, Newark NJ

2007 Gold and Silver Jewelry: The Transformation of a Tradition in the Twentieth Century, State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg, Russia, organized by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

2008 Form and Function: American Modernist Jewelry, 1940–1970, Fort Wayne Museum of Art

From 1951 until it closed in 1966, the Kootz Gallery was the only place that sold Lassaw’s pendants. Later his work was sold in a number of galleries, but mostly he sold them from the studio, where he kept a small wooden display case on top of a tool cabinet surrounded by interesting rocks, shells, and crystals.

Collectors and galleries

The following are some people who I know at one time owned at least one Lassaw bosom sculpture. While Lassaw and galleries that represented him sold many bosom sculptures, not every sale was recorded by name, so this list includes mostly people who were our friends or had connections in the art world.

One of Lassaw’s early customers was Nelson Rockefeller, who bought 10 pendants to give as gifts. I think the year was 1952. He came to our loft on 12th Street, climbed three flights of dusty wooden stairs, and paid cash. I was in school at the time and so didn’t meet him. That sale gave us a very merry holiday.

Among our many artist friends who had bosom sculptures, here is a short list, including: painter Charlotte Parks, wife of painter James Brooks; writer May Tabak Rosenberg, wife of writer and art critic Harold Rosenberg, who also had a belt buckle; writer Betty Friedan; photographer Denise Browne Hare; painter Ingeborg ten Haeff; sculptor Mitzi Solomon; art historian Helen Harrison; art dealer Anita Kahn; Agnes Fitz, of the Dord Fitz Gallery; Grace Borgenicht, gallery owner; Jane Kootz, gallery owner; Rose Slivka, editor of Craft Horizons; Harriet Vicente, wife of painter Esteban Vicente; painter Carol Hunt; artist Rosalind Bengeldorf Browne; art historian Ellen Russotto; Judith Zabar; Ester Gottlieb, wife of painter Adolf Gottlieb; Icelandic painter Nina Tryggvadottir, and her daughter, artist Una Dora Copley.

After the Kootz Gallery closed, Lassaw sold pendants in many other galleries around the country, but none of those relationships were as lasting as the one with the Kootz Gallery. The galleries included Elaine Benson Gallery, Bridgehampton, NY; Arlene Bujese Gallery, East Hampton, NY; Merrill Cheney, Santa Fe; Marcel Fleiss, Paris, France; Fontana Gallery, Pennsylvania; Harmon-Meek Gallery, Naples, FL; Henri Gallery, Washington, DC; Galerie XV111, Maryland; Galerie Claude Bernard, Paris, France; Kennedy Galleries, New York City; Sculpture to Wear, New York City; Anita Shapolsky Gallery, New York City.

A number of sculptures and pendants were donated to nonprofit and charity organizations to help raise money for their causes.

Documenting

Each time he finished a sculpture, Lassaw took pictures and recorded it in his Sculpture Book (a loose-leaf notebook), but he never did that for his pendants. He occasionally took slides of groups of pendants but there was no consistent record keeping. The Kootz Gallery kept invoices for each sculpture it received and listed pendants by number, but they never took pictures. Some gallery dealers took pendants from the studio and he kept no record of what they took. Lassaw trusted them, sometimes with later regrets.

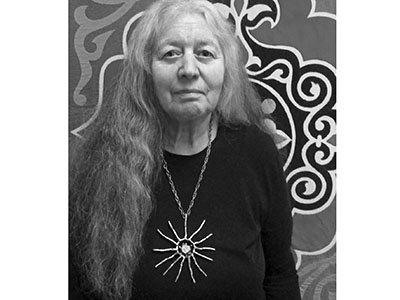

I left home in 1963, the year my parents moved full time to The Springs, East Hampton, New York. Bill de Kooning lived a quarter mile away in one direction and Lee Krasner (Pollock) lived a quarter mile in the other direction. Many other artist friends had also moved to the country because life in the city had become too expensive. I lived in Alaska and traveled around the world, but I spent parts of each year working in the studio. After 1988 I began to organize my father’s papers and photographs and to clean and repair sculptures.

Creating pendants or bosom sculptures was an act of love. Lassaw worked alone in his studio and made pendants when he felt like it. There was never a deadline to meet or an order to fill. His studio was full of light and classical music and often he worked with the barn doors open to the woods or he worked outside in the sunlight, visited by birds. He continued to make bosom sculptures well into the late 1990s when failing eyesight forced him to stop welding. For me, each bosom sculpture is like a sister who has traveled alone out in the world. I am always happy to have news of these tiny travelers.