Shifting Focus—From Hangzhou to Antwerp, from Sculpture to Jewelry

Shifting Focus—From Hangzhou to Antwerp, from Sculpture to Jewelry

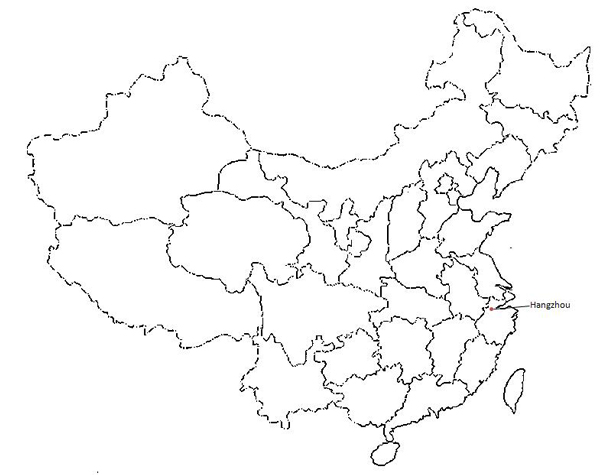

Wang Zhenghong is a graduate of the academy herself: She first obtained a bachelor’s degree there, majoring in sculpture, and went on to complete a master’s degree in soft material and fiber art. In 2003, Wang Zhenghong was already a famous artist in China when she moved to Antwerp, Belgium, and enrolled in the jewelry class at the Antwerp Royal Academy of Fine Arts, from which she graduated with an MFA.

As she acquired the technical skills for jewelry making, the ideas for Wang Zhenghong’s pieces grew based on the experience of everyday life in a foreign culture. Coming from Hangzhou to Antwerp was a cultural shock. Wang Zhenghong remembers for example her first impression: “Coming from China, Antwerp was too quiet for me. It’s like there are almost no people there.” To me her works from this time seem like a diary that tells of the difficulties of bridging cultural boundaries and of longing for home back in China. Let us consider, for example, her work Tea and Coffee Offering Set (茶与咖啡系列).

Offerings Tying Bonds—Coffee and Tea

Even before coming to the West, Wang Zhenghong had been a coffee lover. During her life in Belgium, meeting people to drink a cup of coffee and the conversations around this played an important role in creating bonds, smoothing over cultural frictions and bridging the language barrier. On the same lines, sharing tea with locals in China and learning to appreciate the varieties of green tea and the customs around it, offer a deep insight into the Chinese culture and are openers for conversations.

The cups from the Tea and Coffee Offering Set can be unhooked from the necklaces as can the spoon from the Coffee Set. The tea or coffee offering is all “at hand,” worn on the body. Wang Zhenghong sees this series also in the light of making a cultural bond between East and West, or from the perspective of Chinese philosophy, merging the yin and the yang, two partial identities that only in combination create wholeness.

The way in which Wang Zhenghong chose to express this idea might seem too obvious at first glance. However, the work gains unexpected strength through its close association to the body: This illustrates that bridging cultural gaps is not a process that only takes place in the mind but has to be embodied in its literal sense. Sharing food and drink is very vital in bonding cultures and especially works if other forms of communication such as a shared language are not available. The one who offers welcomes the foreign guest, the one who accepts shows the will to interact with a new culture. Hence, the work points to a set of complex issues behind the banal activity of drinking tea or coffee.

Jewelry—Sculpture for the Body

When Wang Zhenghong eventually returned to China and presented her new ideas on jewelry, she was greeted with enthusiasm but also confronted with comments like: “When you went away, you made sculpture, now you make craft.” In such cases, Wang Zhenghong likes to reply with, “Jewelry is art, it is a wearable sculpture.” She is intrigued by the possibilities that jewelry offers: “Normally, you see sculpture in a museum. You can’t make a connection to it through your body. If you wanted, you would need to touch it and this is usually not allowed. I want to connect sculpture with people and through that I want to connect cultures.”[1]

In Wang Zhenghong’s opinion, the question of whether the piece is wearable is not important for it to classify as jewelry. Instead, she thinks that the most important characteristic of contemporary jewelry is the idea behind the piece, just like in contemporary art. To implant this idea in her country has been her goal since her return to China and the start of her career at the China Academy of Art.

Teaching—Offering and Exchanging Artistic Experience

The jewelry department at Hangzhou was established in 2004. In the first years of its existence, it depended on cooperation with manufacturing companies. Students were sent to these companies to get some training in production techniques. Thus, at the academy, the students were taught how to design jewelry but not how to make it. When Wang Zhenghong was asked in 2008 to found the jewelry studio, she worked toward a program more closely aligned with the studio jewelry model: Now, students do get a background in jewelry techniques, among them traditional Chinese skills.

Wang Zhenghong established exchange programs between Western institutions and artists and her department. Looking back on her own time abroad, she believes that it is very important for the students to get exposed to new ideas, new ways of working, and a new cultural environment. In 2010, the first student from Hangzhou’s jewelry department went on a trip to Europe. This trip resulted in some joint projects with the Escola d’Art del Treball in Barcelona, Spain.

As still more students from China come to the West to study contemporary jewelry, in the near future, the exchange might run also in the other direction. China seems to be in a process of rediscovering its own cultural heritage. Much of this heritage got destroyed and forgotten during the cultural revolution, but is now being rediscovered in China’s search for a new cultural identity between modernity and its ancient roots, and in the dialogue between East and West.

Fusing Jewelry with Art and Chinese Identity

Fusing Jewelry with Art and Chinese Identity

Wang Zhenghong recently finished her PhD thesis. In it she analyzes, among others, the work of Alexander Calder; of Marjorie Schick, a jeweler who creates body sculptures that combine aspects of jewelry and sculpture; and of Bruno Martinazzi, a sculptor and jeweler whose topic is the human body.

The practical part of Wang Zhenghong’s PhD illustrates her shared interests in jewelry, sculpture, and body. Her work consists of a combination of sculptures as mountains on which small objects such as pavilions are placed that can be taken off and worn on the body.

With the sculptured mountains and the way she presents them in her installations, Wang Zhenhong intends to allude to the water and mountains depicted in Chinese traditional landscapes and gardens. As in Chinese gardens, the water is not physically there but is suggested by the empty spaces between the sculptures.

Western viewers might feel somewhat familiar with the idea of mountain/water and landscaping because Asian (mainly Japanese) gardens and bonsai arrangements have been around in the West for quite some time. However, others of Wang Zhenghong’s references to Chinese Daoist philosophy are less obvious.

Some ancient Daoist medical texts portray the internal texture and circulation of the human body as a macro-microscopic landscape. The human organism is seen as a reflection of the society. The individual organs are embedded in a bureaucratic and administrative hierarchy, just as people are embedded in social and administrative structures. According to Daoism, micro- and macrocosm share the same structure and follow the same rules, all of which can be observed in everyday life and then be transferred onto the inner body. Lung, heart, spleen, liver, and kidneys, for example, are seen as five independent administrative centers connected by a complex system of transit routes to build an integrated whole. Each administrative center has governors, and the governors rule over subjects. The blood, for example, is a subject of the heart, which is the governor. The heart itself resides in the “palace of the small intestine.”[2]

Some ancient Daoist medical texts portray the internal texture and circulation of the human body as a macro-microscopic landscape. The human organism is seen as a reflection of the society. The individual organs are embedded in a bureaucratic and administrative hierarchy, just as people are embedded in social and administrative structures. According to Daoism, micro- and macrocosm share the same structure and follow the same rules, all of which can be observed in everyday life and then be transferred onto the inner body. Lung, heart, spleen, liver, and kidneys, for example, are seen as five independent administrative centers connected by a complex system of transit routes to build an integrated whole. Each administrative center has governors, and the governors rule over subjects. The blood, for example, is a subject of the heart, which is the governor. The heart itself resides in the “palace of the small intestine.”[2]

Alluding to principles of Daoist philosophy, Wang Zhenghong’s idea is that by wearing the jewelry, the human body is transformed into a landscape, and thus becomes a representative of the cosmos as a whole. A closer observation of the “mountains” in Wang Zhenghong’s installation, for example, reveals that these also refer to body parts.

The Daoist principles are depicted in several illustrations, one of them being the Nei Jing Tu in the Baiyunguan temple (Temple of the White Clouds) in Beijing. The Nei Jing Tu portrays the body as an internal landscape, into which structures such as pagodas, gates, and palaces are depicted that refer to different body parts and their symbolical and alchemical meanings. Below the thorax, for example, a 12-story pagoda is depicted that is similar to Wang Zhenghong’s pagoda brooch. The 12-story pagoda, a Daoist term, originates from the quasi-anatomic shape of the trachea, with its 12 rings that overlap one another.[3]

While this is the background of Wang Zhenghong’s work, a Westerner looking at the brooch in the form of a pagoda will most likely see exactly this—a building or monument that can be worn on the body, one not unlike the miniature Eiffel Tower souvenirs that tourists can buy in Paris.

According to Wang Zhenghong, however, the wearer performs a symbolical act by wearing her sculptures, turning the inside of his or her body to the outside. Western viewers might not have access to this part of interpretation, but this does not seem to bother her. She even perceives it as an advantage that her jewelry may be filled with different meanings depending on the viewer’s location and cultural background: “My jewelry sculptures are wearable parts of the landscape [that] can move and make connections between time and space in very different ways. The wearer can change places. It is possible to be in Hangzhou in the morning, to be in an airport in the afternoon, and to be in Paris on the following day. The parts of the traditional landscape change places and also the reaction and interpretation of the spectator will differ according to his cultural backgrounds.”[4]

Function and Connectivity of Chinese Contemporary Jewelry

After being exposed to Chinese contemporary jewelry and talking to some of the artists, I find several interesting aspects in this art form: In contrast to other Asian countries like Japan or Korea that also went through the cycle of returning to tradition in order to find their own cultural origin,[5] huge parts of China’s cultural heritage were not only forgotten for some time but were actively destroyed and meant to be erased from the collective memory. Hence, returning to it means to reestablish it in the collective mind, to get proud of it again and to establish a new cultural identity fusing the traditional with the modern. Contemporary jewelry plays a not-to-be-underestimated role in this process.

Some of Chinese contemporary jewelry takes up traditional techniques. Wang Zhenghong, for example, includes traditional weaving techniques in her work; artists like Zhang Fan work with ancient filigree techniques and put them into a modern context; others, like Chen Tsu-Ju, employ an ancient technique of using kingfisher’s feathers in jewelry. Yet other artists, like Teng Fei, Shannon Guo, or Wang Zhenghon, revive more than traditional techniques, materials, or aesthetics, but refer to the “immaterial” cultural heritage through Chinese proverbs or ancient philosophic concepts.

Some of Chinese contemporary jewelry takes up traditional techniques. Wang Zhenghong, for example, includes traditional weaving techniques in her work; artists like Zhang Fan work with ancient filigree techniques and put them into a modern context; others, like Chen Tsu-Ju, employ an ancient technique of using kingfisher’s feathers in jewelry. Yet other artists, like Teng Fei, Shannon Guo, or Wang Zhenghon, revive more than traditional techniques, materials, or aesthetics, but refer to the “immaterial” cultural heritage through Chinese proverbs or ancient philosophic concepts.

Fusing tradition, the things people already know, with a new concept has always been fruitful, not only in art but also in other areas like religion or politics. It is an approach that makes the most of the relationship between old and new, in order to smooth over the frictions that change inevitably brings, making it popular. Hence, referring back to Chinese heritage will certainly help popularize contemporary jewelry in China. Taking up the principles of ancient philosophy might even close the loop and keep the traditional Chinese heritage fresh in the mind of a young generation that seems rather more interested in modern life and social media.

But what about the West? What about the well-established group of Western academics, artists, galleries, and collectors that mainly represent, define, and judge contemporary jewelry at the moment? Will Chinese contemporary jewelry become as popular as its Japanese or Korean counterparts? There are certainly cultural boundaries between Asian and Western cultures—what kinds of qualities does jewelry need in order to cross those boundaries? There is a demand for jewelry work to make cultural identity manifest. But how much and what kind of cultural identity are we expecting/tolerating? Is it a question of pure aesthetics that attracts us or not, or are we interested in more? I view the works by artists like Wang Zhenghong, Shannon Guo, Teng Fei, and others as offerings from China—they offer an entrance to explore another culture and another way of thinking. This might be a fascinating journey, full of new impressions and new thought-provoking impulses. However, as is also true for physical journeys to places far away—it takes time and determination.

[3] David Teh-Yu Wang, “‘Nei Jing Tu’, a Daoist Diagram of the Internal Circulation of Man,” The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery 49/50 (1991/1992): 141–158. (Accessible here.) There is no room here to further delve into the symbolic meaning of the pagoda. For more information, see for example Ken Cohen, The Way of Qigong: The Art and Science of Chinese Energy Healing (New York: Wellspring/Ballantine, 1999).