Born February 4, 1934, Evergreen, Illinois

Died April 2, 2015, Deer Isle, Maine

Today we make jewelry and wearable art from any material that we choose, but it was J. Fred Woell who in the 1960s broke the rules and paved the way for art jewelers. Fred pioneered the concept of using found objects and cast-offs and was into recycling long before that term was coined.

In 1964, Fred made his first found-object piece, a pendant entitled Fetish, as a reaction to being told that he must work in gold if he wanted his work represented in a New York City gallery. The notion that the worth of one’s work was dependent upon its material value was counter to Fred’s beliefs, so he chose to make what some later called “anti-jewelry,” or jewelry with no intrinsic value. Fetish was comprised of a square of wood, a torn stamp, broken glass, and staples. The entire piece was varnished and then set afire to give the pendant an aged appearance, or, as Fred later called it, a “rusticated” look.

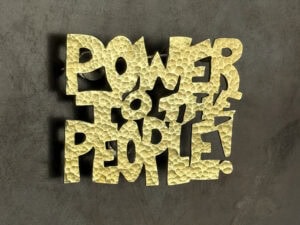

Through his jewelry and sculpture, Fred expressed his thoughts and reactions about conditions and situations that exist in contemporary society, and he used discarded materials as a statement against the waste and excess in American culture: “I make things I hope people can laugh at and yet take seriously. I use my work as a platform to express my reactions to things I see around me; I use humor in my work to make the serious nature of those things bearable.”

Around 1970, Fred began a series of cast pieces using plastic toys and model car parts that he melted, manipulated, and cast to create pins, boxes, small sculptures, and spoons. Not having the money to buy casting silver, Fred “recycled” the sterling silver flatware from his first wife’s “hope chest.” Fred and Kathy were more into Dansk stainless than sterling, so this worked out well, and the stainless knife blades were eventually repurposed with handles made of precious metal clay.

When teaching at universities and workshops, Fred always attempted to bring out the creative voice of the students, offering guidance and encouragement, all the while expanding the students’ life experiences and not just their technical skills. Music, film, books, and humor were part of the working vocabulary.

Undeterred by the stroke he suffered in 2009, Fred continued to work in the Deer Isle, Maine, home studio he shared with his wife, artist Patricia Wheeler, until a few days before his death.

Always true to his beliefs, and generous in sharing his skills and knowledge, Fred was among the most important artists in contemporary crafts. Attention to detail and, most importantly, to the world around us is the lesson that he attempted to communicate. Those of us who knew him also remember a treasured friend with a dry wit, great laugh, kind spirit, and his prized recipe for lemon sherbet.

J. Fred Woell: Art Is an Accident, a retrospective exhibition of his work, is on view at the Metal Museum in Memphis, Tennessee, until June 12, 2015, and an exhibition catalog is available.