The corona outbreak had only just become an unavoidable fact, the International Fair (IHM) was canceled, most intercontinental jewelry lovers had stayed home, and the program in Munich was thus diluted when the newly curated Danner Rotunda opened for a press preview on the morning of March 13, 2020. The omens were bad.

A handful of people gathered and listened to six speeches before there was time to have a proper look around. The speeches, by the curator of the Design Museum, Petra Hölscher; the director of the Neue Sammlung, Dr. Angelika Nollert; the president of the Danner Foundation, Dr. Gert Bruckner; and the three new artist-curators of the Danner Rotunda—in short, an illustrious company—were very informative. That afternoon the gallery closed, not because of corona but for regular safety measures, while nobody realized that the museum would lock down the next day for an unknown period of weeks or months. Therefore, I only had a rather quick look, but it was enough to get a good impression.

There are just a few museums in the world that hold a permanent presentation of contemporary jewelry—I’m afraid we can count them on the fingers of one hand. Therefore, a new presentation is something exciting, and important because permanent museum presentations tend to suffer under their permanency. From the very beginning, when the Danner Rotunda opened in 2004, it was clear things would be different here. One of the main differences from other museum collections is the way this one has been brought together as a mutual enterprise of the stately Neue Sammlung museum and the private Danner Foundation. Furthermore, artists and other people from outside the museum have a significant voice in the decision-making, which, in my view, is the only way to build an interesting collection of art or jewelry—that is to say, when it isn’t dependent on issues of personal taste or favoritism, and when it’s the result of thorough discussion, reflection, and consideration.

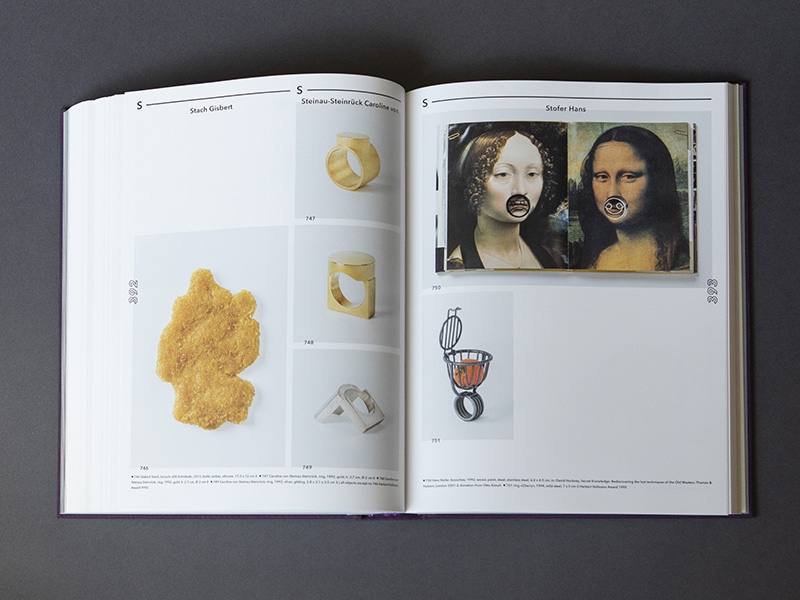

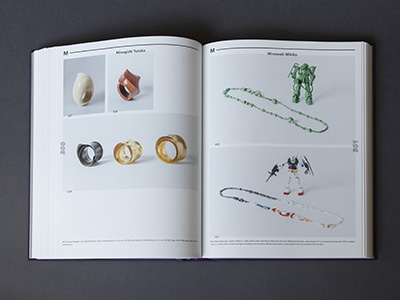

The new curation is the fourth; each one is displayed for approximately five years. Florian Hufnagl (1948–2019), the former director of the Neue Sammlung, who recognized the potency of contemporary jewelry (Autoren Schmuck, in German) and allowed it a place under the roof of his museum, asked Hermann Jünger (1928–2005) rather than the curator of the museum to do the first curation in 2004. He gave Jünger—who, because of his deteriorating health, was assisted by Otto Künzli—carte blanche. Hufnagl had seen some exhibitions curated by Jünger, and in this way he wanted to credit the jewelry world. The second curation was done by Karl Fritsch, the third by Künzli, and now for this new edition—which is called Radar Beeps—the museum invited a team of three artists: Hans Stofer, who is a member of the acquisition committee of the Danner Foundation and professor at the jewelry department at Burg Giebichenstein, in Halle, Germany; Mikiko Minewaki, lecturer at Hiko Mizuno College of Jewelry, in Tokyo; and Alexander Blank, who studied in Munich under Künzli. It’s not an obvious team, but they were brought together by the museum strategically, representing different generations and positions.

They had the difficult task of choosing from the 1,700 pieces in the collection, and making a fresh and inviting display that does justice to all pieces. How do you do that? Relying on their intuition was certainly an important factor. According to Stofer, they started individually by looking for pieces in the collection that appealed to them. Says Stofer: “After that we put the pieces together, looked and discussed, we were looking for dialogues between the objects, like small conversations that all in their own way open doors to the jewelry world.” The curators didn’t use theoretical criteria but instead emotional and spiritual ones, such as “resonance, gravity, and chemistry.” The question of why they chose these pieces, put forward by themselves, was answered with: “that should also be a question for the visitor.”[1] By choosing this approach they hope to stir the joy of imagination in the audience.

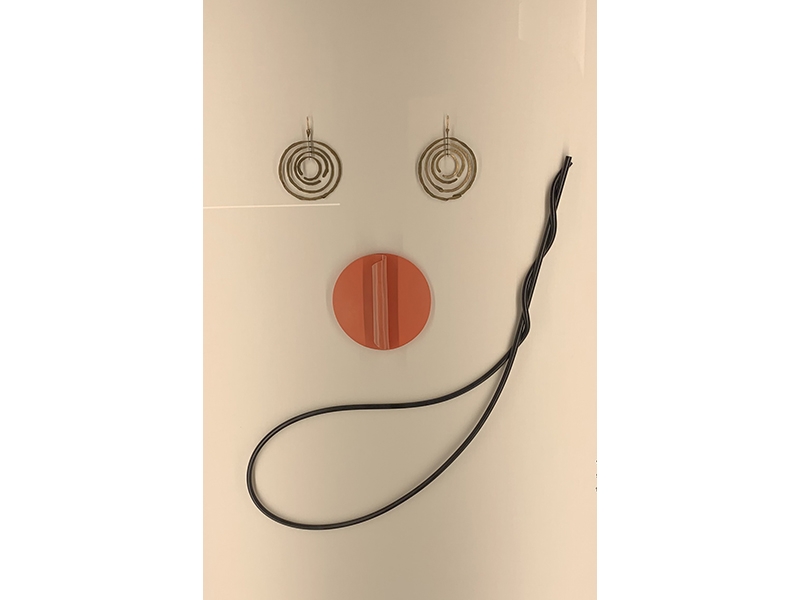

Although the new curation is definitely different from the previous ones, there’s also a consistent feature, which is the associative grouping (and choice) of pieces. In a wall showcase, an emoji is created with the help of two brass spiral earrings for the eyes, a red round plastic pendant for the nose, and a long black rubber and metal chain with a loop that looks like a crooked mouth; these piece are by, respectively, Harry Bertoia (circa 1948, US), Vaclav Cigler (1965, Czechoslovak Socialist Republic), and Johanna Dahm (1986, Switzerland). This grinning “face” brings together cultural backgrounds, historical periods, and artistic motivations that are far apart. Although I like it, I can’t escape the impression that I am being laughed at. I have to grab the handout—awkward, as it’s printed huge, but well known since its first design, in 2004—to look for something to hold on to. How will a visitor who knows nothing or just a little bit about contemporary jewelry, or jewelry at large, deal with such a puzzling display? What is that person looking at, what are we (the insiders, those in the know) looking at? Actually, it is this: jewelry is used as ingredients for a composition. Observed as form, and stripped of meaning, it is the summum of jewelry, ornaments to play around with. Once you realize it, this game suddenly makes sense. As a matter of fact, play is one of jewelry’s etymological origins: jewel > jeu (Old French: game, play) > jouel (Old French: ornament, present, gem, jewel) > jocale (Medieval Latin) > jocus (Latin: pastime, sport; Vulgar Latin: that which causes joy) > see: joke; see: joy.

Another wall-mounted showcase offers more coherence. We see a jewelry sketch, by Bernhard Schobinger, made out of magazine cutouts joined with staples (1984). It’s paired with a delicate wafer-thin gold necklace, by Yasuki Hiramatsu (1972), that looks like cut paper, and a paper mock-up for a brooch by Francesco Pavan (1989). The fourth item in the case, a golden ring, a student work by Fritsch from 1993, completes the story of research and thoughtful experiment that forms the basis of artistic expression.

Other showcases contain striking juxtapositions, such as a pre-historical Transcaucasian votive sheet (well, actually a modern casting of it) with a line pattern indicating face, breasts, and vulva, beside a long yellow steel wire by Herman Hermsen (1983). This display draws the attention of the viewer to the question of how to wear Hermsen’s strange brooch—what will be the effect of this yellow line, 490 millimeters long, on your body, and how would you wear it?

Sometimes the use of materials makes for an interesting confrontation between pieces, such as two Plamo’s pieces, by Minewaki—made of toy parts—with a manufactured piece of fashion jewelry from platinized metal and glass stones, dated 1949, and a big sculptural brooch by Bussi Buhs made of the most mundane materials: polyester, micro balloons, padding, and silk. Or the confrontation takes place on a more philosophical level, for instance between the box filled with Chinese jewelry used for ritualistic funeral burning and Otto Künzli’s Gold Makes You Blind bracelet (1980). Whereas the paper jewelry is used to show off and symbolize wealth while accompanying the deceased into the afterlife, the other piece has banished the gold to darkness and invisibility inside the rubber coating, in this way reversing ideas of wealth, shine, and ostentation.

It’s remarkable how many studies, experiments, editions, occasional pieces, and oddities are chosen for this presentation—this is something you never see in a presentation of contemporary jewelry. A beautiful spatially constructed brooch (2003) painted bright red, by Francesco Pavan, appears to be an aluminum mock-up upon longer inspection. David Phillips, a former student of Künzli at the Munich Academy, is represented by his weird Burn Jewelry (2005), made of burned Pringles cans and epoxy. The crushed and melted forms talk about experimentation and frustration, maybe anger, and about the difficulty of finding your way in this complicated and challenging matter called contemporary jewelry.[2] On the other hand, Gerd Rothmann found his trinkets laying around in 1976, when he decided to fill a big wooden box with hearts made from household items and ready-mades. He only had to tweak some things. The box is a wedding gift for his friend and colleague Claus Bury. In a funny way it refers to the practice of the goldsmith, who can make a living out of fabricating engagement and wedding rings. The box is a nod to old and new customs: to the poor post-war wedding ring that was often forged out of second-hand jewelry brought together by both families, but also to the new social reality of the 1970s, when morals became “loose” and the wedding ring became (temporarily) obsolete. In that sense the box is a document that illustrates a transition in jewelry.

This jewelry presentation tries to position art jewelry within a broader story of jewelry, and by including many experiments, mock-ups, prototypes, and student works it emphasizes the seeking, exploring, inventing, and finding out that is an important part of the practice of today’s art jewelry maker/designer. In my view, the few African pieces deserve a better treatment than just mentioning “Borana, beard jewelry, late 20th century” or “Baule, traditional necklace, 1st half 20th century.” (There are no labels, by the way, only numbers, and a list with minimal information.)

But this aligns with the idea of treating all jewelry, whatever its origin, equally. Even iconic pieces, although represented, didn’t get the lead role in this jewelry play.

A new tradition in jewelry display has come into being in Munich, not along historical, chronological, national, or regional lines, not based on material, technical, or conceptual narratives, but solely on the displayed works themselves. The works have something to tell us, or combinations of works raise questions. So, let them do the work—without explanations, without words. With this approach, the museum distances itself from the educational task—or better, it searches for another education, one that requires more commitment from the visitor, but that also gives you the freedom to just enjoy yourself without having to know. (Die Neue Sammlung has created a virtual exhibition, by the way.[3])

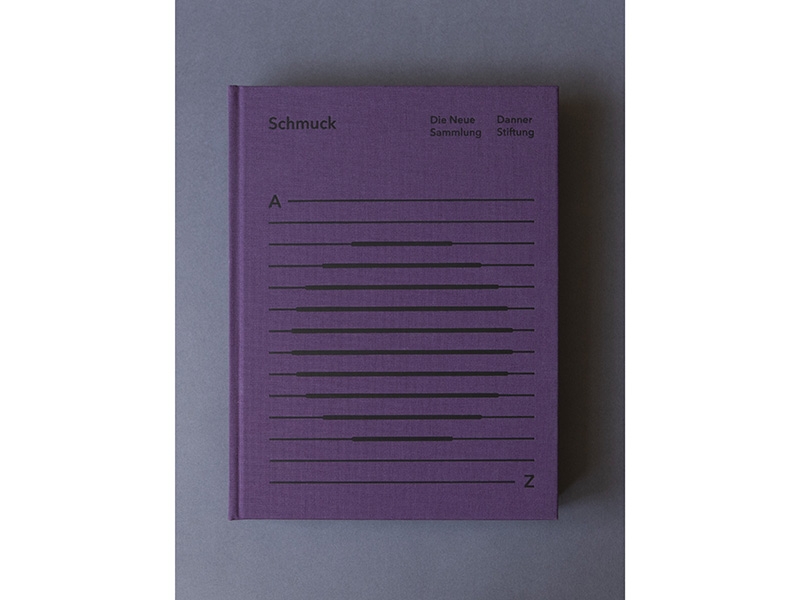

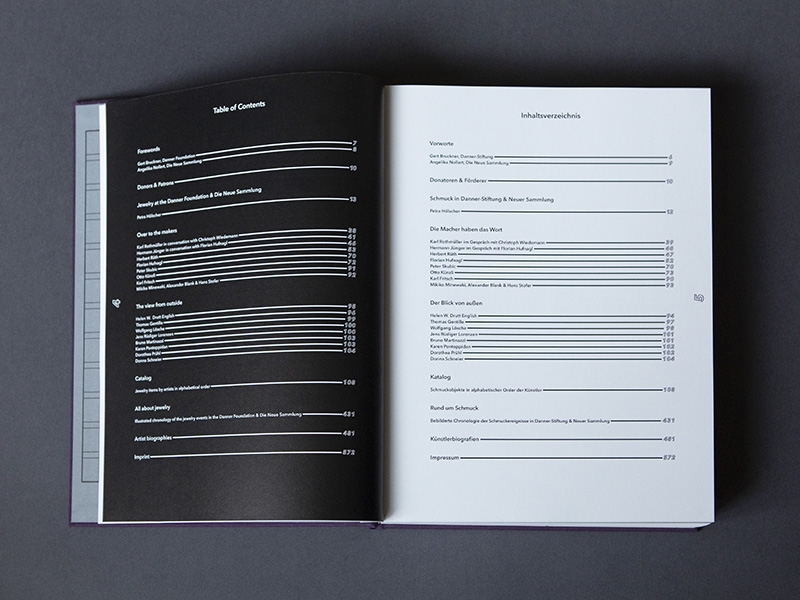

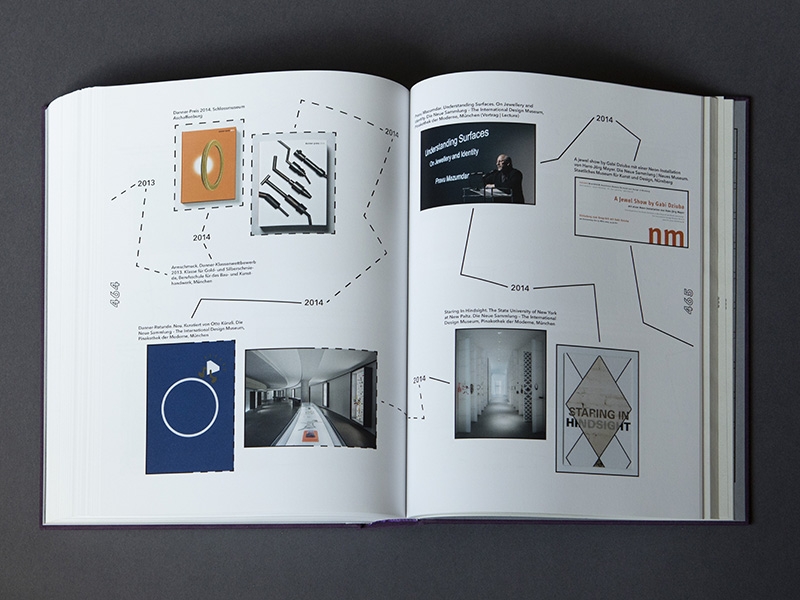

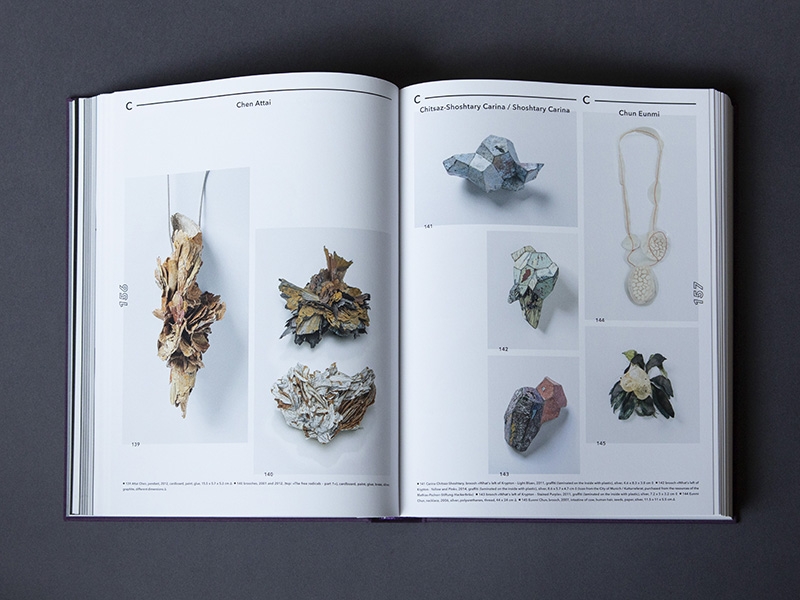

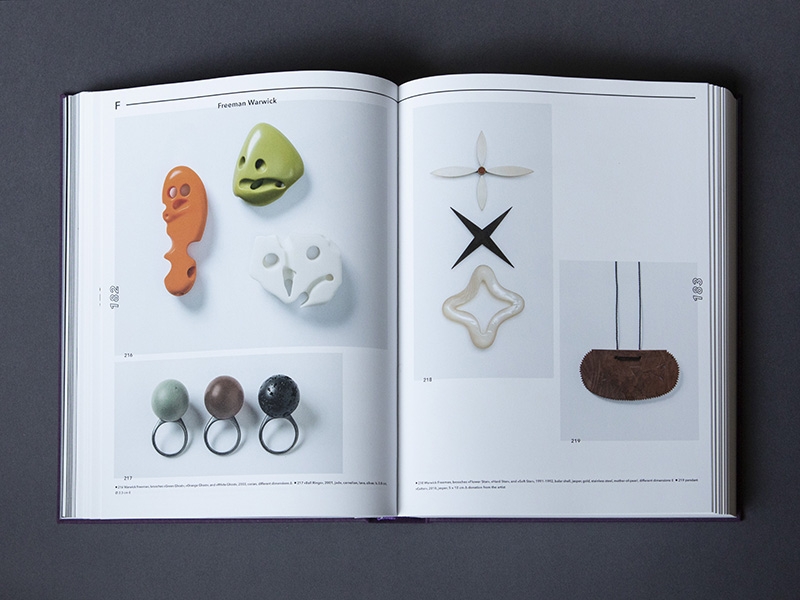

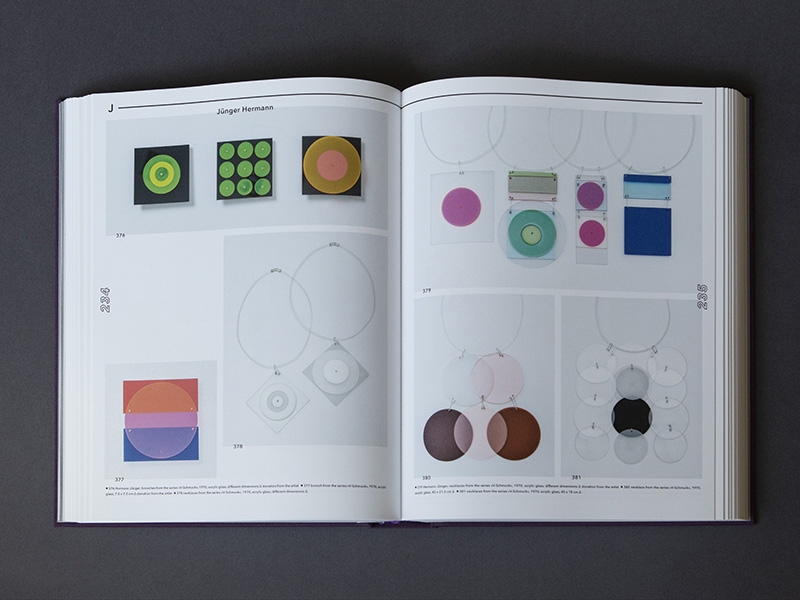

In the comprehensive book accompanying the new curation, Schmuck A–Z,[4] Petra Hölscher renders the history of the private Danner Foundation, which began exactly 100 years ago, in 1920, and the history of the public Neue Sammlung (founded in 1925),[5] down to the smallest detail. To understand how Munich came to have the unofficial status of “capital of jewelry,” it is a must to read this book.

The foundation and the museum, both based in Munich, only grew closer to each other gradually, culminating in the planning of the Danner Rotunda, which was generously financed by the Danner Foundation with an amount of €1.2 million. Initially, a room for jewelry was not projected in the building plans for the new museum area at the Türkenstrasse (which included contemporary fine art, graphic art, and design), but the Neue Sammlung’s director at the time—circa 1995—Hufnagl, recalled how he went looking for a “non-space” in the building under construction, together with Künzli, and found the appropriate one right beneath the central rotunda on the second level of the basement. In the book, Hufnagl remembers that Künzli said, “…in [the] future the art presented on the upper floors would be based on the jewelry. And that would be only fitting, as jewelry was considered the oldest known art form.”[6]

Visitors of Munich Jewelry Week might think that Munich has been a jewelry hub forever, and that some other cities try to copy the event. But there is no template, and the lucky alliance between various institutions, individuals, and jewelry didn’t start as love at first sight. In reality jewelry only became a focal point in the city during the 1980s, when a few dedicated and prescient individuals (Jünger, Hufnagl, Künzli, Peter Skubic, Jürgen Eickhoff, and others) and organizations (IHM, the Academy, the Danner Foundation, and the Neue Sammlung) began to support each other, and chance also played its part. In 1979 Jünger became the head of the jewelry and metal department at the Academy, giving room to jewelry where his predecessor had focused on hollowware. In the same period, he became a member of the jury for the Herbert Hofmann Prizes. The Danner Foundation, in the meantime, became interested in starting an arts and crafts collection, and for pragmatic reasons chose jewelry, which needs only a minimum of storage space—sometimes jewelry’s small size proves to be a unique selling point!

At first the foundation acquired pieces of jewelry from the Herbert Hoffmann Prize winners, but soon began acquiring from other sources, too. This was instigated through the reinforcement of the Foundation’s purchasing committee by two new members in the 1990s: Künzli (since 1991 the new professor at the Academy in Munich for goldsmiths’ art) and Hufnagl (the director of the Neue Sammlung starting in 1990). Now the jewelry collections at the Neue Sammlung and the Danner Foundation started to grow exponentially, and strategically. Hufnagl started acquiring jewelry for the museum collection, while the museum collection was extended by donations from Skubic in 1995 (60 pieces of jewelry), and Jürgen Eickhoff/Galerie Spektrum in 1996 (90 pieces). The fact that the Danner Foundation and the Neue Sammlung agreed on exhibiting the Danner collection as a permanent loan was an important argument for both private donations.

Thanks to the close cooperation between Hufnagl and Künzli, there was a new perspective for jewelry in Munich. Hufnagl, as a museum director, responsible for a design museum, within the context of a museum area including fine art, had not been easy to convince; only the highest standard, one that could compete with the quality of other disciplines in the museum, was eligible. However, some important jewelry exhibitions organized by Jünger and Künzli in the 1990s, along with the ongoing discussion with Künzli, made the director finally change his mind. From that moment on, he himself became a fervent purchaser and explorer of contemporary jewelry.

Unfortunately, accomplishing the idea of exhibiting the Danner Collection at the Neue Sammlung would still take some time. But this gave Hufnagl the opportunity to orient himself even better. Then, in 1993, thanks to the efforts of many people and organizations, the first “jewelry year,” entitled Gold, Gold, Gold, was organized in Munich during the IHM. Many of the exhibitions were financially supported by the Danner Foundation. The event also included the first exhibition of the Foundation’s jewelry collection, curated by Künzli; on this occasion the first collection catalog was published. As a result, Hufnagl asked Künzli to compile a wish list of “must haves.” We can only conclude that the team of Hufnagl–Künzli was very prolific. Both had an international network, and thanks to these contacts important North American works (via Donna Schneier) were added to the collection. Helen Drutt donates a piece to the collection every year. Meanwhile, Jünger contributed to the collection thanks to his contacts in Austria, Padua, and Eastern Europe.

When, on March 5, 2004, more than 2,000 people gathered in the hall of the museum for the historic opening of the Danner Rotunda, Hufnagl saw confirmed that there is an audience for contemporary jewelry.

Besides extensive introductions, interviews with Jünger (2003/2004), Hufnagl, and others, and contributions by different writers, the book contains the complete collection of The Neue Sammlung – Danner Foundation. The pieces are shown in alphabetical order by artist’s last name, and the biographies give profound background information. The inclusion in the collection of some pieces of early- and mid-20th-century pieces of African and other traditional jewelry are an awkward fit. They were probably chosen for their obvious beauty, symbolism, and expressive power, but by presenting them in this context, they’re stripped of their cultural and communal meaning. This becomes painfully clear in the “Artist Biographies” chapter in the book,[7] where, for instance, Bariba, tucked away between the long reference lists for Gijs Bakker and Rut-Malin Barklund, only says: “Westafrika.” Ashanti, Baule, Borana, and Miao suffer the same fate. I think today we cannot just pick from other cultures as we please, the way early-20th-century fine artists did—we should feel responsible to credit these works on their own merits, not only from our aesthetical notions. This is a minor comment on a major project. I have one word for the quality of the book, one often used in the Netherlands with a nod to its big neighbor to the east (and although in these times we are striving to avoid stereotyping, I’ll say it anyway)—it is typical German, it is gründlich, thorough.

[1] All quotations are from Hans Stofer, during the press opening on March 13, 2020.

[2] He has run a successful bicycle shop, called Guten Biken, in Munich since 2010.

[3] View it at https://bildwerk.art/Rundgaenge2020/Danner_Rotunde/Danner_Rotunde_2020_short_version_07.html.

[4] Petra Hölscher, ed., Schmuck A–Z (Stuttgart, Germany: Arnoldsche, 2020).

[5] The Neue Sammlung is located under the same roof as the Pinakothek der Moderne, so it may seem like one museum. The Neue Sammlung is one of the oldest design museums in the world, its history going back to 1925. The Pinakothek is the museum for modern and contemporary art. Both museums have been on the Türkenstrasse since the opening of a new building in March 2002.

[6] Hölscher, Schmuck A–Z, 61.

[7] Hölscher, Schmuck A–Z, 481–570.