Metalsmith magazine’s 2010 exhibition in print was curated by Garth Clark, a writer, curator, historian and ex-dealer gallerist who has been a leading commentator on ceramic practice. Titled Neo-palatial: A Curatorial Imaginarium, Clark’s curatorial conceit is to imagine his exhibition taking place in a faded eighteenth century palace in Europe that used to be occupied by a minor prince and now stands empty. ‘The palace has been reduced to its fundamental structure: white cubes and rectangles of pleasing proportions with faint remnants of rococo ornamentation peeking out from countless coats of paint,’ writes Clark. ‘Traces of its past remain: a fireplace here, ceiling moldings there, the dilapidated but once grand patterned marble floors and other ghostly hints of an aristocratic life formerly celebrated within these walls.’

‘Palace and Cottage’ is an attack on the ACC and its disconnection from what Clark calls the Craft Nation – ‘something vast, unquestionably real and yet deeply mystical, much of it transient but beguiling, driven by an atavistic urge to make, some of it professional, some of it hobbyist, some of it pure catharsis.’ In Clark’s metaphor, which is intended to articulate a ‘class schism’ between ACC and the Craft Nation, ACC is the palace and represents the ‘palace crafters – the stars, the aristocrats of our nation.’ He suggests the philosophy of the ACC is identical to trickle-down economic theory, in which the emphasis is on giving resources to the rich in the belief that wealth will trickle down to the middle and lower classes. Craft, represented by the ACC, did the same, giving 90 per cent of its resources to the top 5 per cent of craftspeople.

The result, argues Clark, was that craft entered its Versailles period, lasting from 1980 to around 1995. Prices soared and ‘Craftsmanship responded to the mood of greed, becoming bloated and pointlessly virtuosic, and excess was the dominant aesthetic.’ Craft believed that it had become fine art and the discourse reflected this lack of restraint and perspective, with ‘ordinary little craft objects’ groaning under the weight of quotes from French poststructuralist philosophers.

The cottage exists in contrast to this palace craft. It is small-scale, mostly rural. While the sector contributes between sixteen and twenty billion dollars to the American economy, cottage crafters earn around $24,000 a year, and sales are to tourists and craft buyers rather than collectors, with the median price for objects being $198. This, as Clark, notes, is living on the edge of extinction – for individual makers and also for craft as a movement.

This polemic must have gone down like a cup of cold sick for members of the audience invested in the ACC and been an exciting bloodletting for everyone else. Clark makes some good points and his talk does suggest something of the important sea change that is affecting craft practice. While I think Clark might have provided a more detailed analysis of the conditions that sustained palace craft, he certainly nails one of craft’s most urgent problems – its existence as a desiccated, possibly dying practice on life support provided by a few powerful and rich collectors who have so much invested in the field that they can’t allow it to fail and whose resources are (poorly) covering up the lack of any real or substantial connection with the world at large. It’s hard to imagine anyone denying the force of that argument; certainly contemporary jewelry is guilty as charged. And, faced with the fin de siecle moment of palace craft, versus the vigorous and culturally meaningful practice of cottage craft, who wouldn’t decide to throw their lot in with the latter?

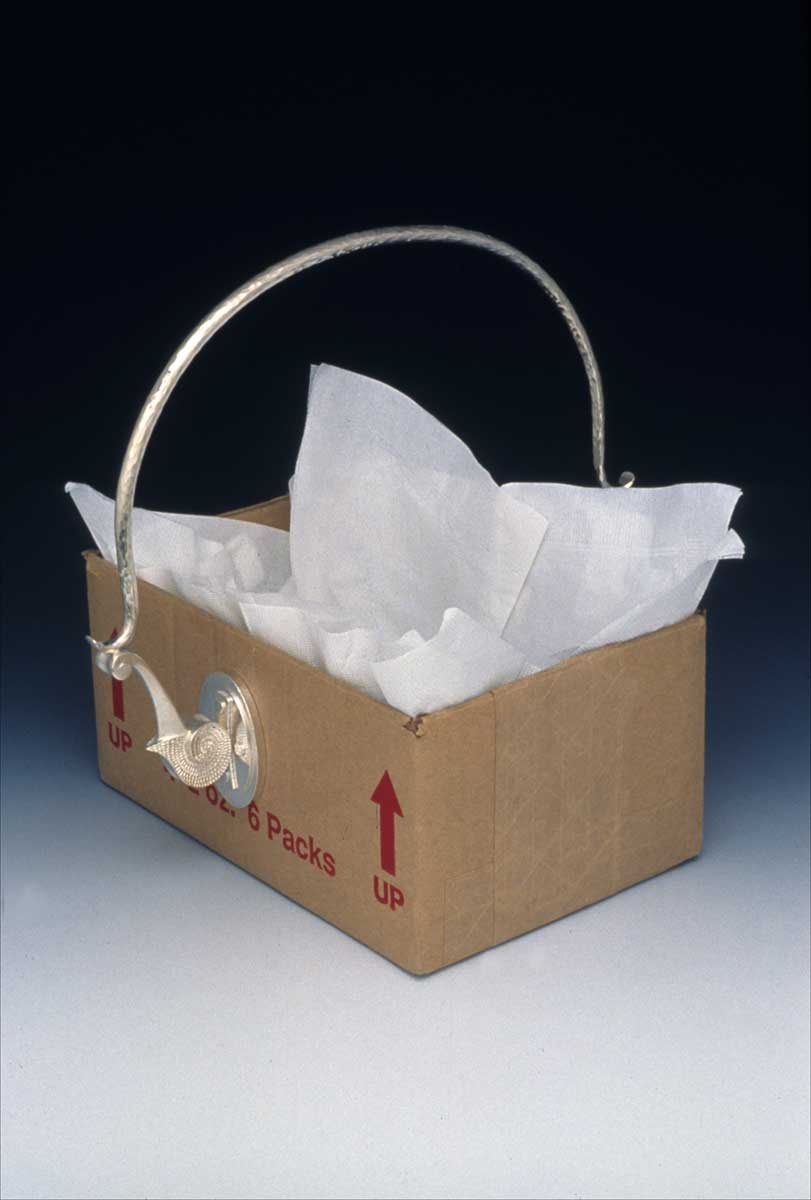

Which brings us to Neo-palatial. In his explanation of the theme, Clark suggests that the palace is ripe for overthrow. While only a few years ago the palace lifestyle was celebrated and envied, even emulated, the financial crisis has made the palace into an explosive political issue. Society, no longer enjoying the trickle-down benefits of greed and unsustainable financial practices, has turned on the palace and all it represents. Clark asks, why tackle this subject now? ‘This is the ideal moment to parody and critique the religion of ultra-materialism, a perfect storm in fact. With this in mind, I have selected work that is eccentric, often deliberately vulgar and with an overall aura of wit and wickedness that delights in the faux opulence of fabricated glamour. But a warning to those with more traditional taste: this palace is much more Lady Gaga than Lady Diana.’ Clark sees evidence of a fertile encounter between the eighteenth century’s exaggerated style, dedication to fashion and interest in craftsmanship, luxury and invention and the contemporary moment. ‘History is wont to repeat itself: these two gilded ages are squinting uncertainly at each other.’

Like any exhibition, the success or failure of Neo-palatial is not to be found in the individual parts, but in the way they cohere, the engagement with issues or themes, the resonance of the subject. There are a few works in this exhibition in print that I find uninteresting but the same can’t be said of the exhibition as a whole. I have happily spent a few hours reading Clark’s text, looking at the images and making repeat visits to his palatial imaginarium. It is a thoroughly enjoyable show, with just the right amount of contentious content, so you are pulled along by the narrative and yet have plenty to dispute or argue with as you travel the rooms of the palace.

Clark finishes with Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog (Magenta), which was installed at Versailles in 2006, and the criticism that its presence in the palace evoked. (The same happened with Takashi Murakami’s exhibition in the same venue.) It is a perfect ending. The conservative critics who were protesting the conjunction, seeing it as an inappropriate meeting of the historic/sacred and the banal, missed the point as Clark suggests, since Koons is the cultural equivalent of Versailles for our time. Yet Koons’s work is not cultural critique of the kind that makes viewers comfortable. ‘He is too implicated, as much an aristocrat to today’s palace establishment as Louis XVI was in his time.’ Sumptuousness, notes Clark, ‘can be an antidote to the clinical oft-sanctimonious austerity of modernism’s more fundamentalist strains.’ Yet this opposition is tainted since we are all complicit. ‘The palace is a place that appeals to the voyeur in all of us. Love it or hate it, we all want to peek over the walls.’

This exhibition in print makes the most of the value of artifice, which at its best opens up into reflexive self-consciousness. Such over-the-top and extraordinary objects as Clark gathers together in Neo-palatial foreground their character as constructed and artificial. Through an exaggerated emphasis on an object’s fabricated nature, we experience what art does best – to put into question the naturalness of our conception of the world and thus open up a space for critical reflection on our own condition.

Clark’s return to the palace is not a recapitulation of previous values or a lazy change of mind, because his return accepts and adjusts to the irrelevance of palace craft. The palace that Clark constructs here is not one of high seriousness and high theory, but one of compromise and complicity. Palace craft of the kind supported by the ACC lived in a belle epoque age and didn’t know it. Clark and his makers are not naive in the same way. Clark’s palace is ruined, not like the polished, urbane glitter of craft fairs and museums in which doubt or compromise is banished. Clark’s palace is suffused, to some extent, with the spirit of cottage craft, which doesn’t turn its nose up at faded aristocratic glamour but tackles it with gusto and pleasure.

Which leads me to one final observation of the wit of Clark’s strategy and subject. In putting together this exhibition in print for Metalsmith, Clark is working for a vehicle of palace craft. It is inevitable that the limitations of this situation would impact on his project

– and it’s very smart that he turns them so adroitly into an opportunity.