This year’s three winners of one of the most prestigious awards in the field of contemporary jewelry each have very different approaches. They work with very different materials: Jounghye Park with silk; Nikita Kavryzhkin, stones; and Eija Mustonen, metal. I interviewed them about their ways of thinking, their sources of inspiration, and the issues they highlight through their work.

- Jounghye Park (from South Korea) uses silk in an eco-friendly way, connecting her pieces to the traditions of her country

- Nikita Kavryzhkin (from Russia, based in Germany), with a background in architecture, transitioned into jewelry-making six years ago

- Eija Mustonen (from Finland) explores themes of boundaries and safety in her work

Jounghye Park Connects with Ancestors through Silk

Elena Karpilova: Silk is the main material in your work. Why silk? Is there a particular story behind how you started using it?

Jounghye Park: In Korea, our traditional clothing, the hanbok, is almost always made from silk. It’s not something people wear every day—it’s saved for very special moments like weddings or big holidays.

When I was a child, I was completely drawn to the bride’s hanbok. It was so colorful and elegant, and I found it mysterious that the fabric came from silkworms. They’re more than just [weaving and sewing] techniques—they carry the beauty and wisdom of many generations.

Using silk helps me feel connected to the wonder our ancestors must have felt—and through my jewelry, I hope to share that same feeling with others.

When did you start exploring natural materials and ecological themes in your pieces, and why?

Jounghye Park: I was deeply influenced by Jeremy Rifkin’s perspective, which identified climate change as the root cause of the broader ecological and systemic crisis. Another major influence was a documentary about Accra, Ghana. It showed a landscape literally formed by mountains of discarded clothing from around the world. The image that seared itself into my memory was of cows chewing on scraps of fabric from these massive piles. It was utterly shocking.

That story forced me to confront a reality in my own studio: the ever-growing pile of fabric scraps. To create my pieces, I dye silk, sew, and cut the fabric. For every piece that is born from my scissors, or due to dyeing mistakes, another pile of “useless” scraps or discarded fabrics is created.

What are some of the environmental issues in Korea that concern you or influence your work?

Jounghye Park: I live in a building with 20 households. Every morning, I’m surprised by how much trash comes from just our building. It worries me, especially seeing how much of it is from single-use items. It makes me think about how easily we throw things away—things that are cheap, small, or made to be used just once.

I also feel uncomfortable that my creative work naturally produces some waste. I hope that continuing my work doesn’t just add more trash to the world, but instead becomes a way to talk about reducing waste and caring for the environment.

What plant would Jounghye Park love to have in her dream garden? Find out in our Instagram rapid-fire Q&A, here.

From Architecture to Jewelry: Nikita Kavryzhkin

You have a background in architecture. Interestingly, other jewelers also come from an architectural background. For example, Empar Juanes, one of last year’s Herbert Hofmann Prize winners, trained as an architect. Do you feel that your architectural education has influenced your jewelry practice in any way?

Nikita Kavryzhkin: My architectural education and practice have had a direct influence on my jewelry work—just as they would impact any creative discipline. I don’t tend to separate creative practices into strict categories—for me, working with form, regardless of the medium, comes from the same place. Of course, each field has its own functional aspects and specific demands, but the foundation remains the same.

Architectural education, in my view, is one of the most universal artistic trainings. I studied at the St. Petersburg Academy of Arts—a very traditional, academic institution with a demanding, years-long preparation process just to be admitted. This kind of extended, classical approach to art education—including painting, drawing, sculpture, composition, and more—gives a deep understanding of and sensitivity toward form, composition, texture, color, and proportion. And that’s the foundation for any visual art.

Why did you decide to switch to jewelry?

Nikita Kavryzhkin: In fact, my very first encounter with jewelry came at the peak of my archaeological obsession, in 2014. Inspired by ancient Russian jewelry, I carved a pendant in wax, bought some gold, found a jeweler to cast it, and then finished and polished it myself with improvised tools. As you might guess, it was a gift for a girl I had a crush on. Let’s just say it was an experiment in both jewelry and romance—with mixed results.

The shift to jewelry happened just about a year before I started my MFA studies in Idar-Oberstein, in 2019. At that time, I had already been working for five years in one of the biggest architectural studios in St. Petersburg. The day-to-day routine of working in an office came to a point where it outweighed the creative part.

Tell us more about the series Blessed Are the Meek or Squaring the Circle and The Little Prince.

Nikita Kavryzhkin: The series Blessed Are the Meek or Squaring the Circle takes its title from the nine Beatitudes. Meekness and humility, central to many religious traditions, also carry meaning beyond them. This series reflects on these ideas, drawing from personal experiences, inner conflicts, and a process of questioning.

I aimed to represent these concepts visually through minimal yet expressive means. The final piece, Quadrature of a Circle, references an unsolvable geometric problem, symbolizing the pursuit of seemingly impossible ideals. Just as squaring the circle is a futile endeavor, meekness and humility can feel unattainable.

The series Little Prince was inspired by the balance between the visible and the invisible, the literal and the symbolic in the famous book by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. That’s exactly what I try to work with in my own pieces—shapes and materials that speak quietly and subtly, but carry weight. I like that that book is not moralistic. It opens space. The baobabs are not just trees, the rose is not just a flower—everything stands for something greater, yet remains very simple.

When it comes to a favorite quote, it’s hard to choose just one, but here is one among many:

“A baobab is something you will never, never be able to get rid of if you attend to it too late. It spreads over the entire planet. It bores clear through it with its roots. And if the planet is too small, and the baobabs are too many, they split it into pieces …”

What would Kavryzhkin be if not an architect or a jeweler? Find out in our Instagram rapid-fire Q&A, here.

The Beauty of Lakes and the Power of Setting Boundaries: Eija Mustonen

Which three words might describe your artistic approach?

Eija Mustonen: This is difficult. I just called my friend Helena (Lehtinen) and these might be my words today: seeking clear thinking, seeking fearlessness, essentially rustic.

In your opinion, do your pieces reflect the Finnish spirit or culture in some way? If so, which series in particular? And how does that come through?

Eija Mustonen: I believe that the rural culture of eastern Finland and the aesthetics of my childhood home have had a significant influence on my work. This is perhaps most clearly evident in two of my series of works.

A couple of decades ago, I spent a few months in the Netherlands, where I found myself feeling homesick. I missed Finnish nature, the space around me, the forests, and the waterways. I started to rethink what jewelry is to me. I turned these values of jewelry into my own values. What is beautiful, rare, and precious to me? Beautiful and precious to me is the landscape and especially the lakes, water in general, around me in Finland. The shapes, colors, and materials tell about the relationship with tradition and my own background. This series is called Höytiäinen.

Some years later there were deaths and sorrows in my family, some relatives and friends had passed away. In the old times, people used to wear a piece of jewelry to show they were mourning. I have made plain forms of traditional pendants and used “mourning” materials such as black silver, horn, and ebony. I expanded the theme to Finland, to land we had lost to Russia, Lake Laatokka and islands in the Gulf of Finland. The jewelry is cast in silver; the pieces are heavy and dark, as is grief.

You’re well known for your series of works that protect and shield the wearer. Themes like shelter and safety are becoming increasingly relevant around the world. What does it mean to feel protected, for you personally?

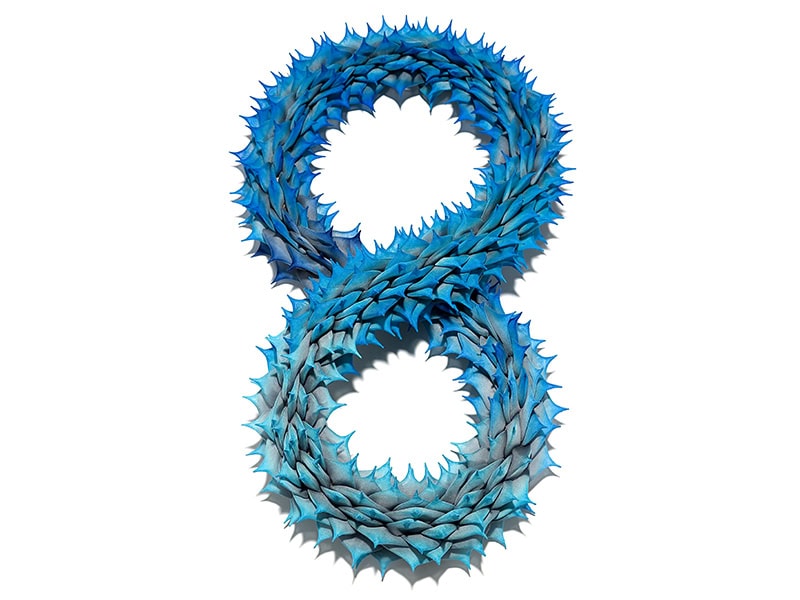

Eija Mustonen: I started making works related to protection about 10 years ago. These works combine blacksmithing techniques with general protection. I hammered metal protective equipment, mittens, and aprons. Metal transforms these originally soft materials into armor-like garments. The theme expanded to include more general protection, both physical and mental. After all, protection is also about setting boundaries.

I live in rural eastern Finland, near Lappeenranta, about 15 kilometers from the Russian border. The border between Finland and Russia is 1,343.6 kilometres long and includes both land and maritime borders. As a result of the war in Ukraine, the border between Finland and Russia is closed. This is a major change for the region. In these turbulent times, the theme of protection takes on an even stronger geopolitical dimension.

If Eija Mustonen had to choose just one material to work with, what it would be? Find out in our Instagram rapid-fire Q&A, here.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2025 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org