- In is new iteration, Melbourne’s Funaki Gallery operates at the intersection between gallery, retail, and domestic space

- Interacting with jewelry in a salon setting results in a more intimate experience

- The gallery is showing work beyond jewelry, when it makes sense

Funaki Gallery is embedded in the cultural fabric of Naarm/Melbourne. A recent move has seen the contemporary jewelry gallery depart from the white box archetype we know so well and transition into the domestic sphere/space. The new larger space is both roomy and intimate all at once. Chatting across a kitchen counter with Katie Scott, Funaki’s director, about the jewelry she shows in her new elegant spaces is a new experience for this interviewer, the mellow tones of the space infusing our conversation.

Vicki Mason: Katie, the last interview you did with AJF was back in 2013. At that point, you had been the owner and director of Funaki for three years. You have now been at the helm for 13 years and have recently moved the gallery. Tell us about the new space. How did it come into being?

Katie Scott: I can’t believe it’s been 10 years since that interview, and 13 that I’ve owned the gallery. I guess this is what I’m doing when I grow up! Funaki moved in October last year, after more than two years of operating online. The Crossley Street gallery was shuttered at the beginning of the COVID lockdowns, along with a lot of other businesses. It was a seismic shift in Melbourne’s landscape, and an existential challenge, but I saw it as an opportunity to try something new. So, I risked doing what I’d long dreamed of but otherwise wouldn’t have dared—leaving the shopfront behind.

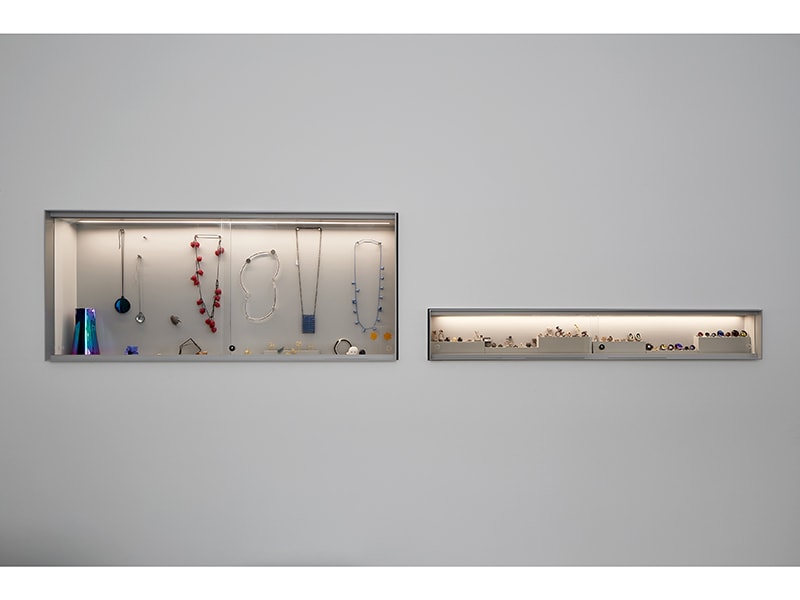

I’m now embracing a more experimental model at the intersection between gallery, retail, and domestic space. Funaki is now located in a third-floor apartment in a wonderful old building, Sackville House, built in 1927 for garment manufacturing before becoming one of central Melbourne’s early conversions to residential apartments in the mid 1990s. The design for the gallery was done by Simon Whibley, of Workshop Architecture (to whom I’m very lucky to be married!). We gutted the existing two-bedroom apartment and transformed it, embracing the industrial history of the building. There’s a central exhibition space with a large pivoting wall to change how the space operates, depending on what’s being shown. The living room forms the retail space, where people can sit and have a cup of tea while exploring our range, and the bedroom doubles as a second exhibition space for smaller project shows. We don’t live in the apartment (though we might stay there occasionally after a boozy dinner), but it’s a fully functioning domestic space, too, with kitchen, bed, bathroom, etc., so visiting artists can stay.

With respect to the fit-out of the new spaces in the apartment, were you able to reuse items from your Crossley Street gallery, or is everything new or bespoke?

Katie Scott: There are two things I brought from the old gallery—the mirror and one set of drawers. The mirror because it’s a beautiful object, custom made for Mari’s[1] original gallery in the 1990s by the wonderful carpenter/artist Zeljko Markov. And the drawers because they exemplified the Funaki experience that made the gallery so well-loved: a leisurely wander through a world of jewelry, all within a few square feet. Everything else is custom-built for the space.

What tone have you sought to achieve with the new gallery?

Katie Scott: I was really interested in capturing the sense of a “salon” rather than a shop. Visitors can experience contemporary jewelry and objects more intimately this way, and it encourages those wonderful conversations between visitors who otherwise don’t know each other. The experience of operating for over two years without a physical space was very influential in this. I was visiting clients at their homes or offices, or at cafes, sharing a coffee and a chat as we did business, and I started to realize I not only loved working this way, but I was better at my job. The connections were more meaningful, I was more relaxed—that pressure of “will I make the rent this month?” was removed, as was the anxiety of waiting for people to walk through the door each day. Funnily enough, it led to better sales, too.

So naturally I was keen to find a way to bring that intimacy and autonomy into the next iteration of the gallery. I wanted to build an experience, not just a space; a place impeccably crafted, where you can immerse yourself, have a cup of tea, flick through a catalog, and think about how these remarkable objects might enrich your own life and home.

Do you think the reading of work shown is affected by the intimate nature of these domestic spaces?

Katie Scott: Yes, I do, and it’s something that, from the outset, I intended. I wanted people to think about how to live with contemporary jewelry in their own homes. You’re not always wearing it, of course, but it can be an important part of your environment even so. To only understand crafted objects in the context of a gallery or museum can be a bit boring. Being in a domestic setting, they can get activated in a different way. My friend, the photographer Fred Kroh, and I planned a project early in the pandemic, before the apartment gallery was dreamed up, where we’d photograph clients’ collections in their homes, to show how they “lived” once they left the gallery environment. That project got stymied by rolling lockdowns, but it was an element in my thinking about this new model.

I also imagined that the reading of jewelry and objects might gain breadth from their context alongside other designed objects, so we’ve been very selective about furniture and furnishings. A life of good design (including but not limited to jewelry, of course) is a good life!

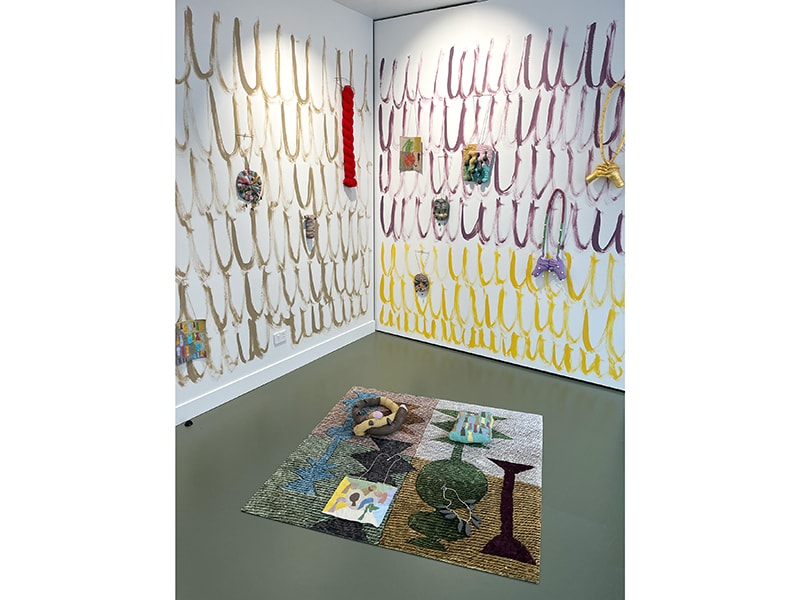

What do you hope for with the new space? I ask this because I saw you recently showed a textile artist’s work alongside a jeweler’s work. Are you broadening the scope of the space to show other art forms?

Katie Scott: As I developed the idea for this new space, I became obsessed with the apartment gallery model as it exists in places like New York, Paris, and parts of Asia. There are great precedents of this idea—the famous gallerist Leo Castelli opened a gallery in his New York apartment in 1957, for example. Contemporary spaces like Amelie, Maison d’Art (Paris) or Object & Thing (NY) each have their own particular feel and scope. In some cases, they operate as a kind of film set with constantly shifting presentations, and everything you see is for sale: the furniture, the lighting, the art objects, and the work on the walls. In this way, the hierarchies between art forms are dismantled. It’s very democratic. There’s no “design,” “craft,” and “art,” there’s just interesting work and how it all sits together. There’s always a place for the white cube, obviously, but I think people are more open to blurring the boundaries now. I find that model really interesting.

So, yes, I am showing work beyond jewelry when it makes sense to. It’s a slow process and I have a lot to learn about a lot of other art forms, but it’s exciting to consider recontextualizing jewelry, thinking about how it can sit in a domestic space with ceramics, furniture, or anything else. I’m keen to see what conversations develop. Showing New Zealand artist Vita Cochran’s textile works alongside Manon van Kouswijk’s ceramic objects and jewelry in November last year was one of those moments where the works came together perfectly. Each was given different perspectives by being shown together. But it’s also important to note, the move toward “more than jewelry” is driven in large part by the artists. They are now more engaged in diverse artistic practice and collaborations. Objects and drawing, at the very least, are often a part of their practice. As a representing gallery, it’s important to be able to support this.

Can you outline how you develop your exhibition programming schedule and how you plan out your year?

Katie Scott: It’s about finding a good balance of local and international content, and of approaches, materials, and ideas. I usually program a long way out, but sometimes it’s about opportunity—if I have an unexpected spot and someone is ready with a good body of work. Sometimes I get too excited about all the things I want to show, and I forget I’m only one person.

What are some unexpected benefits that you’ve discovered in having an apartment gallery?

Katie Scott: Having the occasional nap.

How did Funaki weather and cope with the pandemic?

Katie Scott: I know the pandemic was incredibly hard for a lot of people and my situation was luckier than most, but at the risk of sounding glib, it was a crisis I didn’t want to waste. Closing the Crossley Street gallery, pivoting online, and waiting to see how things panned out gave me valuable time and space to think about and plan the next chapter (and in Australia, some of us were very fortunate to have the government support to allow this pivot and time to plan). Without that, I wouldn’t have had the guts to transform the business in the way I have.

How do you think the pandemic affected the Melbourne jewelry scene, given the strong presence it has as part of the cultural fabric of the city?

Katie Scott: It’s been tough and continues to be so for a lot of people. I think both at an individual level and a community level, the Melbourne jewelry scene has been pretty knocked about. I know a lot of artists had no financial support (the government support I mentioned was not available to artists, which was a travesty). Add to that a sudden, extended removal of social and even family support, and limited access to (non-home based) studios for long periods… I know for some people there are persistent mental health issues that linger because of all this, and to some extent, a temporary disconnection between practitioners who would once have had more to do with each other. I have no doubt our community will come back and come back strong, but it’s going to take time. Events, like Radiant Pavilion, that bring our community together will help enormously; I’m thrilled it’s coming back in 2024.

For those readers thinking about opening a gallery, what advice would you give them? What one key bit of advice would you offer?

Katie Scott: Ha, that’s a tough one! There are so many things to consider—but just one key thing? I’d have to say respect. Respect your artists and respect yourself. Don’t do it for the glamour (because any glamour is illusory)—do it out of deep respect for the field, the artists, and your own vision.

… but having some capital behind you doesn’t hurt. Financially, it’s no walk in the park.

Do you ever play music in the gallery. If so, what do you listen to?

Katie Scott: I never used to, but I do now. If there’s no music, the background noise is generally the drilling rig at the construction site next door. Some gentle jazz keeps things (and most importantly, me) a little calmer.

Would you share something you’ve seen or read recently that captured your imagination?

Katie Scott: I recently read Peter Brannen’s The Ends of the World and it’s fabulous. Terrifying and fascinating in equal measure, it conjures impossibly long-ago worlds and their extinctions so vividly. It’ll forever change your perspective on our short stint aboard this beautiful, benighted planet.

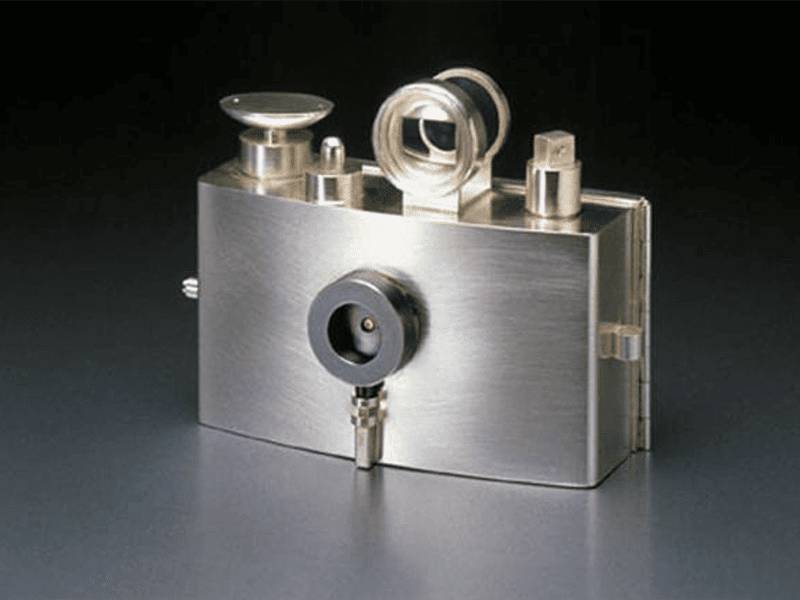

Or, if you’re after something less apocalyptic, I recently learned why Korean artist Hyun-seok Sim started hand-building those astounding cameras in silver. It made me grin and tear up at the same time. I won’t give it away here. By the time this comes out, our interview with him will be online—check our socials!

© 2023 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] Mari Funaki founded Gallery Funaki in 1995.