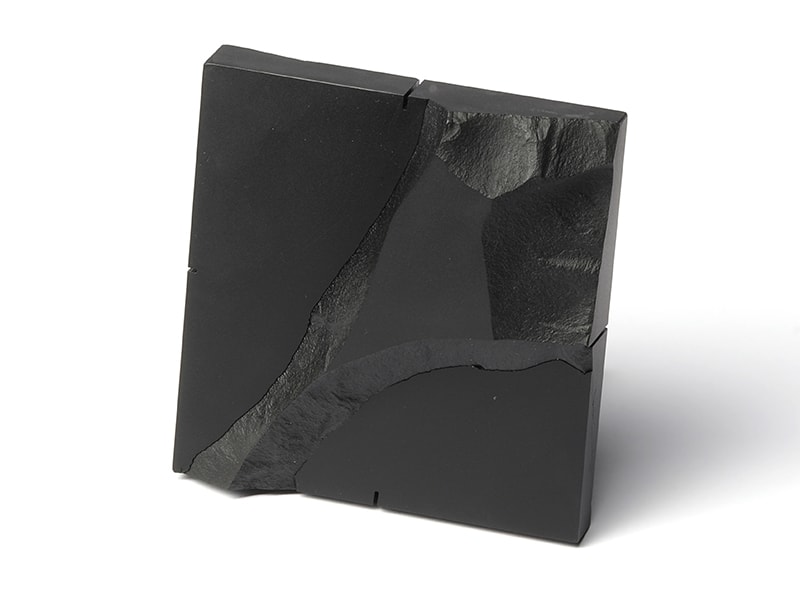

- The world inside a cut-apart stone looks like a universe or a landscape, says Domingues. “You can lose yourself in this microworld”

- She creates lines, fractures, and cuts in both natural and artificial gemstones to craft jewelry that resembles landscapes

- The tension between intentional acts and uncontrolled accidents fascinates Domingues

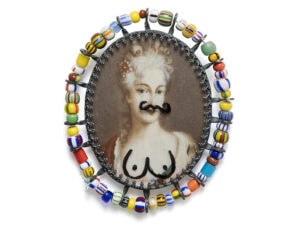

Patricia Domingues works with natural and artificial gemstones in a highly original way. Using reconstructed onyx, lapis-lazuli, aluminum, and other materials, she creates lines, fractures, and cuts to craft brooches and necklaces that resemble landscapes.

Domingues is fascinated by the tension between intentional acts, such as cutting into the material, and uncontrolled accidents, such as the fractures that occur as she works with a hammer and chisel.

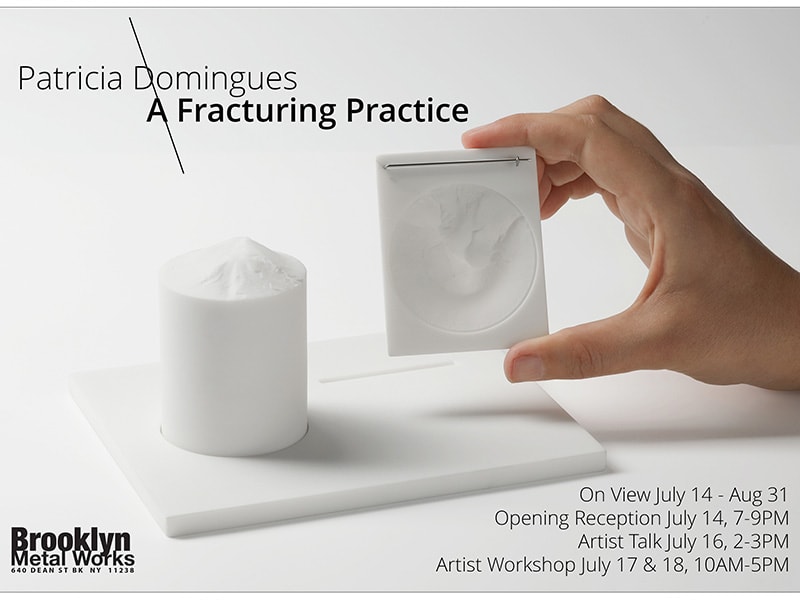

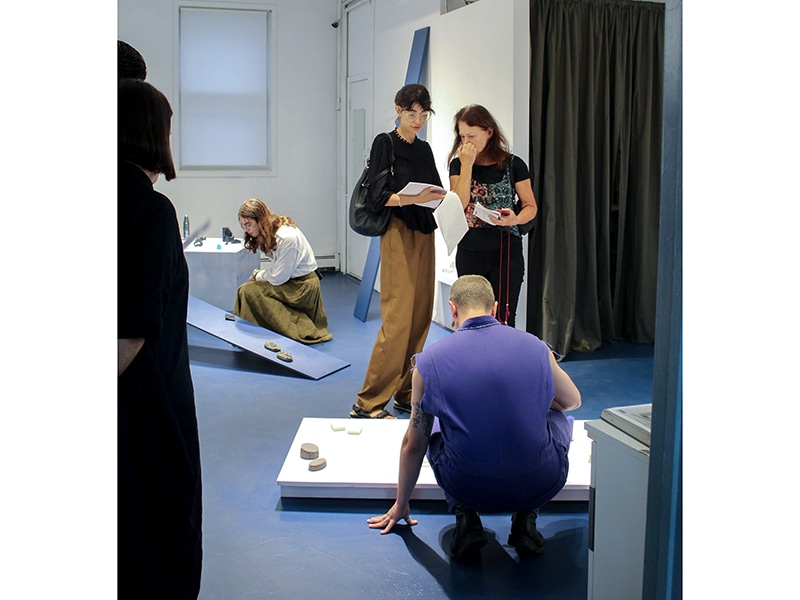

“I look at myself as an intermediator, as someone who initiates actions that end up having a will of their own,” says Domingues. Her first solo show in the United States is called A Fracturing Practice. It’s currently on view at Brooklyn Metal Works, until August 31, 2023.

“I like to think the pieces of jewelry form a link between the immense and the detailed, and present a way to bring a grand-scale aspect of natural and industrial environments into the intimate realm of the human body.”

Domingues is Portuguese but now lives in Germany. She has taken an academic approach to her practice. Last year, she earned a PhD in visual arts from the University of Hasselt and PXL-MAD School of Arts Hasselt. She is currently a research fellow at the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, in Amsterdam. There, she explores the way technology relies on extracting mineral and geological resources from the Earth.

Her work has received numerous prizes, including Munich’s Talente Award in 2014; Australia’s Mari Funaki Award, in 2014; and the Young Talent Prize of the European World Crafts Council, in Belgium, in 2015.

Jennifer Altmann: You have been making jewelry since you were 14, when your mother took you to an open house for an arts high school in Lisbon. What happened?

Patricia Domingues: My mom told me that I could choose any subject but jewelry. Her friend was a jewelry maker, and he was selling jewelry in the street—she didn’t want that for me. I started watching all these videos [about the school]. There was an image of pieces of scattered silver melting as they joined together, and it was this beautiful movement. I thought it was so powerful. I looked at my mom and said, “I’m very sorry, but I have to choose jewelry.”

You moved to Idar-Oberstein, in Germany, to earn a master’s degree in jewelry design from the University of Trier, which is known for its program in gemstones. You still live there today. What attracted you to working with gemstones?

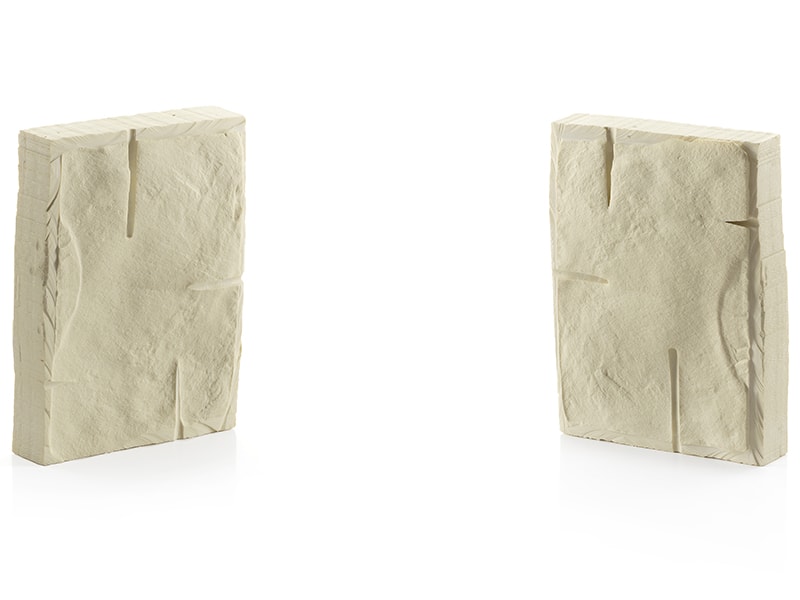

Patricia Domingues: I struggled a lot in the beginning with gemstones. It was a world that was difficult to understand because once you cut a gemstone apart, you immediately see the world inside the gemstone, and it’s such a complex world. It looks like an image of the universe or a landscape, and you can lose yourself in this microworld.

Simultaneously, I came across the universe of artificial, synthetic, and reconstructed stones. These materials are often a combination of resin with stone or metal powder. The differences in origin and material qualities between them have been an inspiration.

On one hand, a natural stone is always a unique element in the sense that, in nature, no two are the same. [But] the reconstructed and artificial material is a massive industrial block. In this case, the idea of uniqueness is lost, since no matter where the material is cut, the result inside is always the same. The artificial material functions for me as a blank sheet, where I can reinvent and reconstruct the observations I have made in the natural world.

The fractures that I am making are a gateway to reflecting on the geological forces of the Earth but also on our fracturing relationship with materials and landscapes. The movement of fracturing has become in my practice a metaphor and a mythology to look inside things.

What is your process of creating a piece from a reconstructed gemstone?

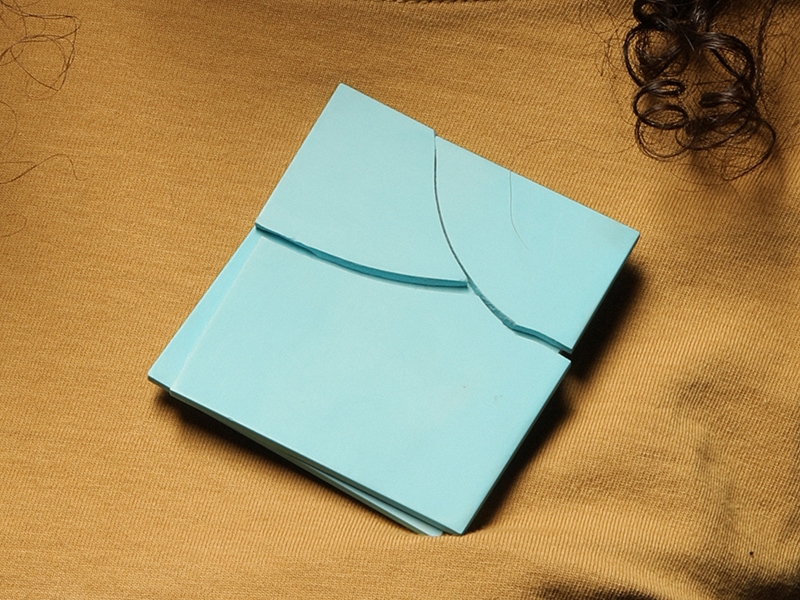

Patricia Domingues: In my studio, using a chisel and a hammer, I attempt to flake a piece of the reconstructed stone that I have previously brought into shape and have fixed on the vise. As my actions split apart fragments from the main piece of material, my fractures seem to be simultaneously an act of creation and of destruction.

You also work with drills?

Patricia Domingues: Yes. Core drills are specifically designed to remove a cylinder of material from inside the [stone]. The material left inside the drill bit is referred to as the core. This kind of technology permits me to reach the inside of my materials in a way that I couldn’t with a chisel and a hammer. Drilling allows me to generate a sort of undercut in the material, so I can in turn provoke what looks like a spontaneous internal fracture. In some of the works, my actions mimic the extractive gestures performed by mining industries.

And you like the unpredictability of the process?

Patricia Domingues: Yes. When I hit the material, I never really know what’s going to happen. I can have a feeling, an intuition, but I can’t really control the results. It’s sort of a controlled accident.

There’s a tendency to perceive craft as a form of control: You master the materials and the techniques. But instead skill can be reinterpreted as a way to relate to landscapes and forces that are beyond our human domain.

The works in the exhibition are made with many different materials, including reconstructed onyx and aluminum, as well as natural materials such as Arkansas stone or limestone. Why did you choose those?

Patricia Domingues: For me, it’s important to be surrounded by materials that I admire. I never work from an idea. It’s not that I have an idea and I go realize it. It’s the fact that I go to the studio every day and live among machines, tools, and a rich material landscape that informs me as an artist.

I have a particular interest in the line between natural and man-made materials, but also in the existing tension between ornamental gemstones. I am interested in the fact that ornamental gemstones, because of their beauty, always seem to have a prestigious place in our lives, at home or on our bodies, while the more practical materials that constitute our constructed and technological worlds are often seen as simple background.

Tell me about using silica, a very common material that we don’t tend to think about very much.

Patricia Domingues: The first time I visited a gemstone engraver in the region, this little cabochon spoke to me because it had a different shine. I asked what it was, and he answered “silica.” I went home and started to research the material. It’s actually silicon, the material that [furnished] the name “Silicon Valley.” It’s in all our smartphones and computers.

What do you hope the viewer thinks about when looking at the exhibition?

Patricia Domingues: The act of making, for me, has become analogous to the act of studying the landscape. I am attached to the idea that not only each piece in the exhibition has a resemblance to a natural scene, but also how, as a body of work, the installation seems to suggest the formation of a landscape. A landscape inside of a landscape.

I want the audience to reflect on the geological forces that formed and continually form the landscape as we know it. I also want them to think about our society’s extractive needs and the way humans objectify and handle the world of stones and minerals.