- The Austrian attorney was—with his spouse, Heidi—an important collector of new jewelry, the term he preferred

- Bollmann didn’t view himself as a collector, but rather as someone who enjoyed purchasing jewelry to give to his wife

- The exhibition Schmuck 1970–2015, held at Vienna’s MAK in 2015, showed roughly half of the couple’s collection at the time, with work by 206 international artists

We met for the first time in Munich. I was an aspiring artist, Karl and Heidi were renowned collectors from Austria. The couple was impossible not to notice. They glowed with a passion and curiosity for contemporary jewelry. I met them through my teacher, Kadri Mälk, who was always amazing at collecting the best people around and also sharing them with her students, making them feel significant and equal in the heart of the jewelry field.

Many great connections between humans are rooted in art, a universal language that binds like souls. We generally saw each other annually in Munich’s hecticness, so I would call it a soul mating. In between, there were some brief letters lighting up the philosophical alleys of the mind.

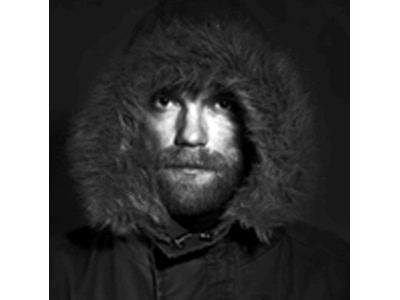

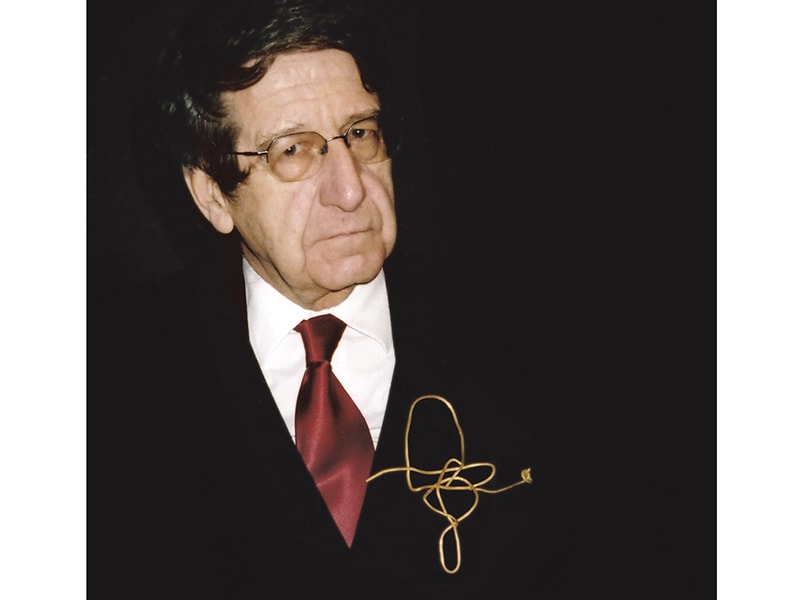

The last time we met, during Schmuck 2019, I had a task. Kadri asked me to make a portrait of Karl for her forthcoming book about her jewelry collection, HUNT:. For this quick portrait—we did it in the Messehalle with my iPhone—Karl chose to wear a wooden brooch by Estonian jeweler Ketli Tiitsar. I wrote to him afterward from home: “It can leave a bit of an empty feeling—passing by, trying to hold a hand for a second—but that’s the way Schmuck is. It’s both good and bad.”

So it is, we mostly saw each other in passing. A hug and a quick “How are you?” And when there’s no longer the possibility of feeling this handshake, sharing a hug, talking from the heart—we might regret terribly never having found the time for precious human contact.

I opened Kadri’s book HUNT: just now and found a quote on the page next to Karl’s smiling face: “It has been said since ancient times /Augustinus/ that people [are] a rational and mortal creature, ‘creature’ occasionally being translated as ‘ANIMAL,’ although ANIMA in fact denotes the soul.”

Karl knew St. Augustine well, and there was so much of a soul in this man—this can’t be a coincidence.

There aren’t too many who are willing to look behind the veil of reality, to dive into the paths of the eternal and the divine. And when Karl did it, there was always a whimsical smirk that distanced him buoyantly from abstract depths of thought. I had enormous admiration for Karl’s intellectual capacity. I felt like a naive schoolboy next to his great mind. Although a lawyer by career, he was a philosopher at heart. He always triggered your mind with deep topics and abstract questions, even in the Schmuck-noise of the Augustiner Keller. He felt like someone from a different era, one where Central European gentleman charm meets impeccable manners.

In 2011, when I was preparing a book about the Castle in the Air (group of six Estonian jewelers) we decided to ask Karl to write an essay for this idealistic project. The text arrived, thick like cream. It was high mountains of thinking, with 27 footnotes from Augustinus to Kant (the latter was his major influence, who he referenced many times in his letters and discussions). I remember the challenge of translating his mindplay from German into Estonian and English. This problem was solved only with the generous help of Kadri’s husband, renowned translator Mati Sirkel, the only one whose mind can face this assignment. Karl started his essay with a quote by John Keats: “I am certain of nothing but the holiness of the heart’s affections, and the truth of imagination.”

Being a lawyer is a challenge of logic, while art is a challenge for the imagination. As an artist I can only admire Karl’s and Heidi’s views as collectors, the worlds only they could see in artists’ creations. I felt that there was a magnetism toward romanticism and melancholy. But it might be my own reflection in Karl’s vision, as he denied me in this perception. Here is a dialogue from emails sent between us in March 2019:

Karl: “I never considered myself as being romantic and I still don’t. I may be wrong. Yet there is an actual need in all of us to accept the beautiful. This is rational.”

Me: “I know I have been teasing you, calling you a romantic before—and as a man of a great mind you turn it into the desire for a pure beauty. Can be, can be … And please don’t be mad when I call you a romantic again.”

There is a notion of this theme in a letter of his from August 2015 which describes the denial and allure of romanticism. But he projected a romantic sense of being onto the artist and his creations. From the letter: “As you know, I am rather not the romantic type, but sometimes I am touched by the transforming powers of the sea. So I picked up a strangely formed piece of wood. It turned out light as balsa, which made me naturally think of you.” And I received this piece of driftwood in a package from Karl and Heidi, another small touching gesture which made you believe in human kindness and significance to each other.

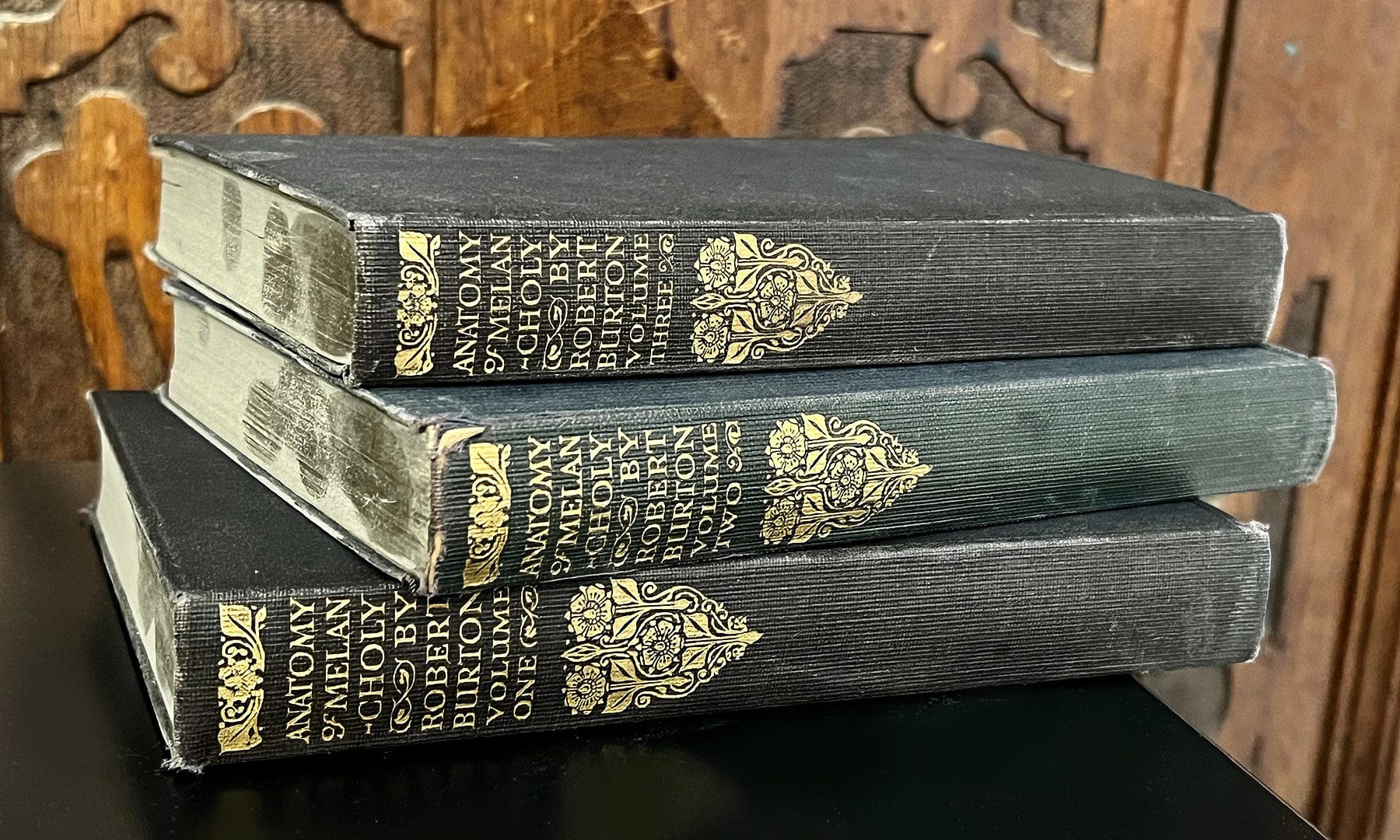

One bridge between us was the sense of melancholy. I think it was 2011 when I received a parcel with three books, among them a charming 1932 edition of Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy. From Karl’s letter from the same time: “I am not a melancholious type and therefore do not know very much of melancholy, only that unhappy or happy ones are struck somewhat erratically. Therefore, a methodical approach to Burton’s anatomy would mean a contradiction. The idea is to take a knife (the best thing would be a completely blunt razor blade) and use it to open the book at random. Then read between three and 10 minutes. Bittersweet feeling: this is just Burton’s notion in his starting poem (beginning with castles in the air) and afterward continuing throughout the book.”

As suggested, I just now took The Anatomy of Melancholy and opened it randomly. From page 218: “Granatus [the garnet], a precious stone so called, because it is like the kernels of a pomegranate, an unperfect kind of ruby, it comes from Calicut; if hung about the neck or taken in drink, it much resisteth sorrow, and recreates the heart.”

There’s not much else to do now than to take a piece of garnet to resisteth my sorrow for never meeting again this wonderful soul.

My condolences to Heidi Bollmann and family.