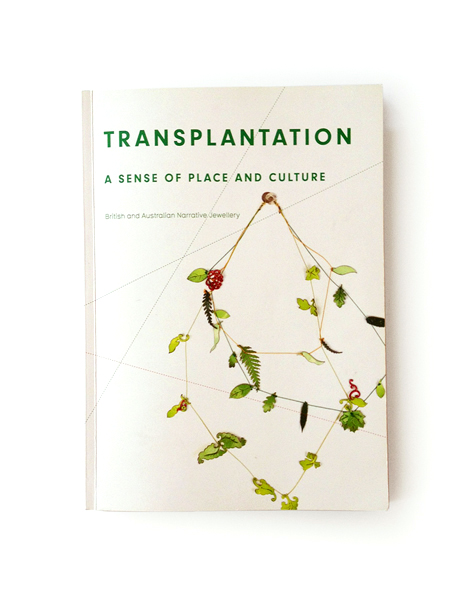

When I finally received the 80-page catalog, my first thoughts were of the fresh and inviting look created by the graphic designer—a mostly white cover with green text and an image of Bridie Lander’s sparse leafy neckpiece. The front and back covers are identical, so you could be forgiven for opening the book upside down and back-to-front. Rather than frustrating, I found this to be a humorous play on the geographical opposition of locations from which the jewelers were selected. An antipodean cover for an antipodean exhibition, I thought. I was delighted to note the inclusion of three substantial essays by noteworthy craft writers Dr. Kevin Murray (Australia), Dr. Elizabeth Goring (UK), and Dr. Grace Cochrane (Australia). I was keen to read what they had to say about the topic of transplantation; their analysis of the work of the exhibiting artists; and their understanding of narrative jewelry.

An introduction by curator and Scottish native Norman Cherry opens the catalog. Cherry notes that his 2004 trip to Melbourne for the Jewellers and Metalsmith Group of Australia’s biennial conference was where the seeds for this exhibition were sown. He writes that “the common history and culture of Britain and Australia naturally opened many conversations, and the subject of a personal sense of place and culture soon became a recurring and dominant theme.” At the time of this trip, significantly his first to Australia, he was delving into Niall Ferguson’s revisionist history book Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World. The few pages regarding the Antipodes in particular inspired Cherry to further develop the concept of transplantation into an exhibition theme. His introduction is an informative read. It clearly outlines what he asked his carefully selected jewelers to respond to, namely to explore their countries shared history and to take stock of how this might resonate with their own experience. While I took note of Cherry’s use of “narrative” to describe the jewelry presented, I struggle in his introduction to find a clear explanation of what he exactly means by it. Perhaps it is his subtle way of telling the audience that there is more to this jewelry. Perhaps he is asking them to look to the stories informing the work rather than just the aesthetic of a piece. He closes the essay by hoping “you will come to think about jewelry in a different way, too: not simply as something decorative to wear, to indicate personality, status, or wealth, or to match the day’s outfit, but an eminently portable, wearable form of art with its own stories, histories, and metaphors.”

“About You: British Narrative Jewelry” by Dr. Elizabeth Goring is the second essay in the catalog, and as the title suggests, it offers up the author’s thoughts on narrative jewelry. In this essay Goring states that, “jewelry is uniquely placed to tell stories” and that because of its undeniable association with the body, jewelry has the ability to be a vessel in “which to explore deeply personal issues, such as cultural identity.” Here, Goring gives us an overview of what she considers to be narrative throughout British jewelry history, from the eighteenth century to the twenty-first century. Not being well versed in British jewelry history, I found this essay to be an informative, interesting read. Goring’s essay also points to the understanding that narrative jewelry is a particularly British (and very American) phenomenon. It bears less resemblance to narrative art than I originally imagined and seems to be only just slightly more defined than what some might call “conceptual jewelry.” I am not sure I was convinced by her arguments about narrative jewelry, but it certainly has me keen to research more on the subject.

In “Across and Back, Between and Beyond,” Dr. Grace Cochrane takes an historical approach to her essay similar to Goring. Instead of discussing narrative jewelry—of which she makes no mention of at all—she guides the reader through a history of how migration (forced or otherwise) brought a plethora of varied experiences and skills to Australia, and how these different waves of immigrants formed the core of what later became technical colleges. Cochrane notes that, “Australian jewelry continues to reflect many consequences of this history, and the transplantation of ideas takes more the form of exchange rather than adoption.” Cochrane makes some astute, if brief, remarks about the varied nature of the exhibited work. It would have been a delight to read more of her thoughts on the individual jewelers, but readers who are not familiar with the chronicle of Australian contemporary jewelry will find this an informative and beautifully written essay.

Transplantation: A Sense of Place and Culture, British and Australian Narrative Jewellery is overall quite a lovely publication. Its fresh look, clean layout, quality images, and extensive content are to be commended. The essays, although at times a little hard going, provide insight into Australia’s and Britain’s past and how that past still influences today’s contemporary jewelers.

Did this exhibition, via its catalog, live up to my expectations? It is clear that each of these jewelers put a lot of themselves into realizing the work they submitted for this show. Some more than others executed thought provoking work that really addressed Cherry’s transplantation brief. Did it showcase narrative jewelry? It certainly did not satisfy my expectations about narrative jewelry as a genre, but yes it certainly offered jewelry with a narrative. I think Cochrane puts it beautifully in the closing remarks of her essay. “These jewelers are keenly concerned with making meaning for themselves though their work, but they are also interested in the relationships that might be formed between their jewelry and its wearers and the ways in which meanings and values might be transferred—or even transplanted—from one wearer to another.” Perhaps, in essence, this is what Cherry hoped we would come to understand as narrative jewelry.