Rosa Taikon: Art and Struggle

Permanent exhibition

Hälsingland Museum, Hudiksvall, Sweden

This article presents the extraordinary Swedish jewelry designer Rosa Taikon, who not only revived modern jewelry art but also a Roma silversmith tradition, which makes her unique in Sweden and internationally. In her dynamic and content-rich art practice, Taikon created jewelry that testifies to an assured sense of design and an ability to combine diverse references into an elegant whole. A skilled artisan who employed time-consuming and patience-trying techniques, Taikon developed an art practice that she would use as a platform for the political struggle for Roma civil rights.

This rich body of work is now presented in a permanent exhibition at Hälsingland Museum. The exhibition builds on a donation from the Taikon family following Taikon’s death, in 2017, at age 90. The result of sterling work by the museum, in collaboration with the Taikon family, researchers, and other experts in the field, Rosa Taikon: Art and Struggle presents Taikon’s art with all its rigor, commitment, and complexity. By reflecting on various aspects of Taikon’s significant art practice, this article will attempt to illustrate the astonishing breadth that you can experience in the exhibition.

In 1961, Taikon enrolled at Sweden’s largest art and design academy, Konstfack, the University College of Arts, Craft and Design in Stockholm, where she remained until 1967, receiving a traditional design education specialized in metalwork. At that time, the department was at a turning point where new practices such as industrial design were introduced and old ones were substantially changed. An example of this change is manifested in the 1959 exhibition Nutidssmycken (Contemporary Jewelry), at Nationalmuseum, in Stockholm, which presented jewelry that transcended its function as discrete embellishment and became a conduit for the subjective expression of the artisan.

In Taikon’s preserved sketches from Konstfack, we see how she produced both hollowware and jewelry, how she was prepared for a career within the applied art industry that would supply the bourgeoise with beautiful everyday objects. Taikon continued to sketch throughout her career. Her Konstfack sketches reveal how she explored her family’s jewelry tradition, exemplified by a sketch of a decorative necklace created by her father, Johan Taikon, a skilled silversmith who learned his trade in Samarkand.

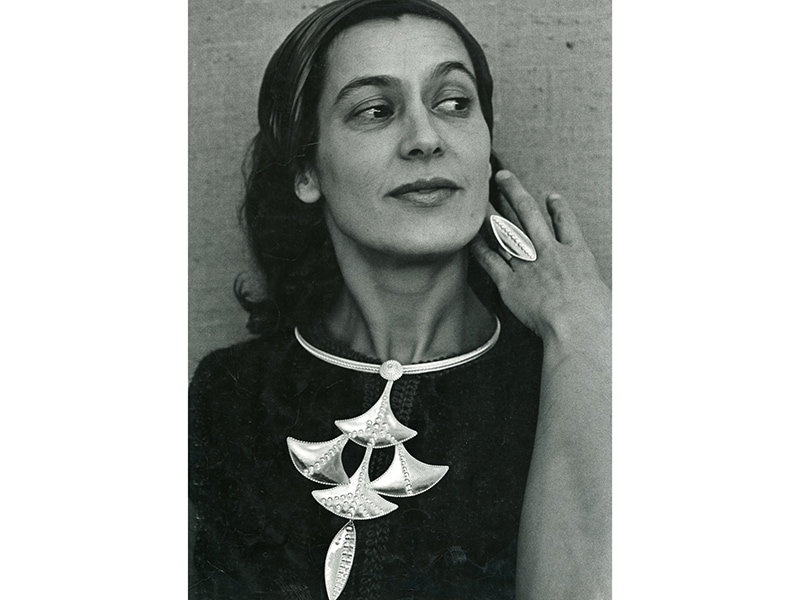

With her Roma background, Taikon was a somewhat unusual Konstfack student. She came from a family of accomplished silversmiths, but none of them had attended any of Sweden’s art academies. In fact, systemic racism had prevented the Roma in Sweden from receiving a formal education there. Silversmithing was only practiced by male members of the family, and while Taikon was inspired by their work, she was also heavily influenced by modern jewelry art.This innovative combination is evident already in the work from her student days. Her graduation project included a belt she created for her sister, Katarina Taikon, is composed of richly decorated silver roundels strung together on a leather strap. Taikon also created a breast piece whose focal point is a richly decorated roundel, the design of which the artist has elaborated into an expressive necklace, amply demonstrating contemporary notions of jewelry as subjective and expressive objects, and successfully merging two essentially different practices into a well-functioning whole.

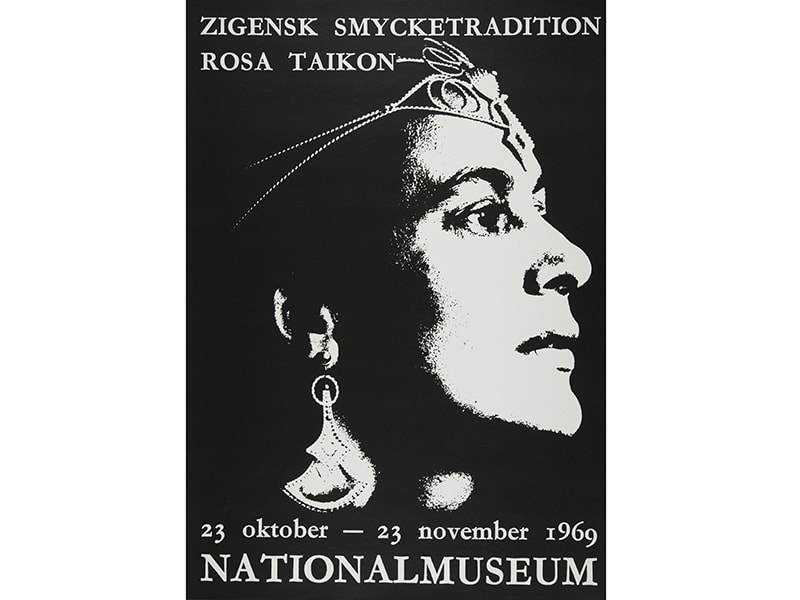

In 1969, two years after graduating from Konstfack, Taikon was given the opportunity to exhibit at Nationalmuseum, in Stockholm. Giving a recently graduated artist a solo exhibition at Nationalmuseum was something very unusual. This must be viewed in light of the political engagement of the time, which followed the so-called counterculture. It influenced the practices and exhibition programs of major institutions and led the museum to offer Taikon a show. The resulting exhibition, Zigensk Smycketradition. Rosa Taikon (Roma Jewellery Tradition. Rosa Taikon) opened at Nationalmuseum on October 23, 1969.

Taikon chose not to occupy the space alone. Instead, in a manner typical of the time, she staged a collective act. The exhibition was created together with her then partner, the architect Bernd Janusch; her sister, Katarina Taikon; and Katarina’s husband, photographer Björn Langhammar. In addition to presenting her own work and Janusch’s, the exhibition included jewelry that had belonged to her family and images showing Roma history and the current social situation of the Roma.

The exhibition would also serve as a platform for the civil rights campaign Rosa and Katarina Taikon were actively involved in. At the time of the opening, the two were engaged in preventing a group of Roma from being deported from Sweden. The campaign was visible in the exhibition, the catalog, and the poster. Visitors to the exhibition encountered satirical political drawings and signs featuring critical statements about the Swedish Migration Agency.

This was a very active period in the struggle for Roma civil rights, and both sisters were deeply involved in it. In 1963, Katarina Taikon published the autobiographical book Zigenerska (Roma Woman), which received much attention. The Taikon sisters were committed to attaining equal rights for Roma. In 1965, they co-founded Zigenarsamfundet (The Roma Association) and the following year contributed to the foundation of the association’s journal, Amé Beschás (We Live), which described contemporary Sweden and its history from a Roma perspective.

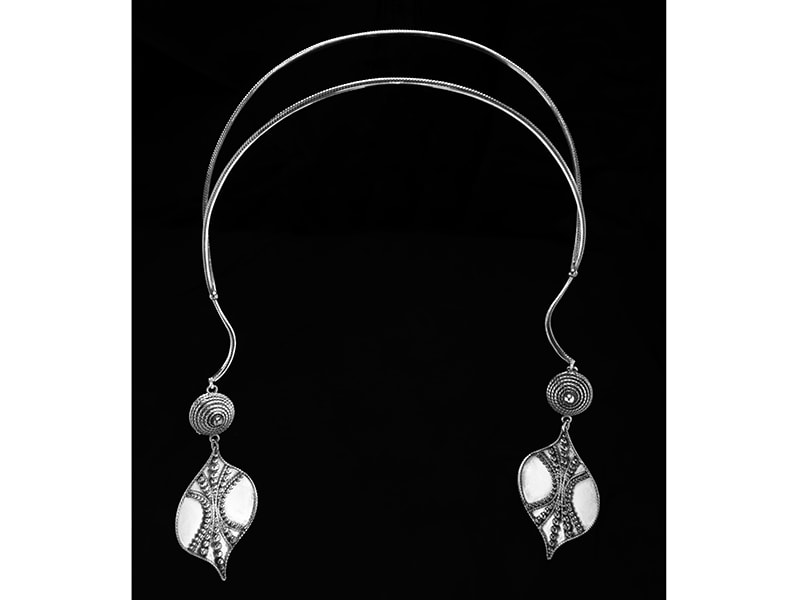

Zigensk Smycketradition differed in terms of its content from other politically engaged exhibitions of the time in Stockholm. This is perhaps most evident in the fact that the basis of the exhibition was Taikon’s precious silver jewelry. At the time, many Swedish makers distanced themselves from precious materials and sought cheaper alternatives. There is no denying that Taikon was radical, perhaps even more so than her peers, albeit in a different manner and on her own terms. Taikon’s design and use of precious materials must be understood as site-specific. That is, they must be read in relation to a specific time and place. Taikon’s meticulous making stands in relation to a craft tradition—from the Roma—that hardly existed in the 1960s and was not at all represented in Nationalmuseum’s history writing. At the same time, her work fulfills the role of expressive adornment.

Until her death in 2017, Taikon remained an important advocate for Roma civil rights. Yet, as we will see, she would somewhat alter how she used her jewelry as part her activism. Her worked changed somewhat when she and Janusch relocated in 1973 to a former school in Flor, a small town in the north of Sweden. For many years they collaborated closely, almost in symbiosis, creating jewelry together and participating in joint exhibitions. An example of their collaborative efforts is the 1983 exhibition Rosa Taikon, Bernd Janusch, Smycken, Corpus, Silver (Rosa Taikon, Bernd Janusch, Jewellery, Holloware, Silver), at Röhsska Museum of Design and Craft, in Gothenburg. It is evident in the exhibition that Taikon’s curiosity in form and craft never stopped.

In the accompanying catalog, Taikon writes about her background as a dancer and musician, describing corporeal experiences that she brought to her making. In the text, Janusch asked her: “Why do we work with silver, what do we want to say?” Taikon answers, “in creativity, in the design, in the feeling and its rhythm.” Now, in the beginning of the 1980s, she described her artistic practice as wordless. She wrote that if the answer could be expressed in words, she would have been a writer. For her, jewelry was a sensuous design. In the catalog text she also expressed her admiration for the “sensualism” and “sensuality of rhythm” of the figures in the Indian Sun Temple at Konarak and in the temple in Bhubaneswar. Although Taikon opened up to manifold references, she always coalesced them into a coherent whole.

Compared to the late 1960s, the beginning of the 1980s was a very different time. Postmodernism made its breakthrough in design. In Sweden, it meant that the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s, with its political activism and social interest, gave way to a greater interest in form. In the piece Solens Strålar (The Rays of the Sun), 1980, the silver is accompanied by gold details that have been given a stricter placement than that usually afforded to silver filigree. It is a piece of jewelry that demonstrates how the artist had changed, a development that always occurred with the same, strong integrity. She continued to create her own, utterly unique idiom.

Already as a student at Konstfack, Taikon had displayed a mature jewelry expression that early on generated much interest. She created work through variations of the same fundamental techniques: filigree and granulation, a motif to which she continuously returned and performed variations on. For her degree project, she primarily created flat surfaces, but soon she would work with more sculptural relief designs. She continually developed new combinations, new motifs, varying the placement of the techniques and the design of the silver. Taikon never stopped. She never ceased being curious and creating new variations, while constantly returning to and reworking old motifs. The exhibition Rosa Taikon: Art and Struggle gives us the opportunity to immerse ourselves in her design world and her indomitable creative energy.

Presenting Taikon’s artistic development may seem obvious. That is how we often talk about artists—we describe their artistic choices and how they change over time. However, this does not necessarily apply to Taikon. Readings of her work tend to emphasize her Roma identity and not pay attention to her whole complex artistic practice. Furthermore, within the mainstream institutions of the majority society, there has been a great deal of ignorance about the Roma tradition she refers to. This deficiency makes it difficult to appreciate how she contributed to renewing this tradition. A telling example can be found at the Nationalmuseum. From her 1969 exhibition, the museum acquired one of her works, Bara Ihlo. This remains the only piece by Taikon in the Nationalmuseum collection, compared to 35 works by her contemporary colleague Torun Bülow-Hübe. Having acquired works from different periods throughout Bülow-Hübe’s career, Nationalmuseum illustrates how her art practice has developed over time. Taikon is only represented by one single work there, and as a result time stands still.

This fact is essential background information in understanding the important work carried out by Hälsingland Museum in creating the Rosa Taikon archive and mounting a permanent exhibition of her artistic practice and her activism. Thanks to the careful work of the museum in creating the archive, researchers will be able to gain knowledge of this significant art practice, and jewelry artists can be inspired by her work. The exhibition will provide the public with the opportunity to learn about this exquisite, expressive jewelry art by a prominent artist and about her life-long struggle for human rights. For those interested in jewelry, the exhibition Rosa Taikon: Art and Struggle is a must.