Susan Cummins: How did you discover you wanted to make jewelry?

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna: I am not sure if I discovered that I wanted to be a jeweler, or if jewelry discovered me. Growing up in an environment of artifact, object, and art, it seemed normal that I should naturally fall into it. I spent a while in my youth travelling throughout New Zealand and dabbling in art and craft, but I avoided taking it seriously due to a lack of confidence and courage. It wasn’t until my mother passed away that I had the epiphany that I had to go to art school and make it happen and that life was too short to have regrets or avoid things. It was also a creative outlet for my emotions at the time. Jewelry was my silent ambassador. It was always there for me and taught me new things. Then, I started to see potential in myself and the others around me. I could use the language of jewelry to relate to others, and not only did it help me, but I could use it to help heal others.

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna: One difference between my technique with stone and those of the past is the technology. In our modern day, we use diamond-impregnated tools, such as sanding disks, drill pieces, and grinding wheels. As the majority of these are machine operated, the motion and movement is faster and easier than the hand carving process.

Traditional stone was carved using an abrasion technique of cutting and grinding. Grooves were made by sawing with hard sandstone or greywacke saws and rubbing abrasive quartz mica schist into this cavity. This enabled the breaking and snapping off of fragments of jade from the block with a wooden hammer. The stone was smoothed by rubbing it against a sandstone, and sand/water hand drills were used to create holes in the piece for flax cords. This was a long process, and often pieces took weeks to carve. When we have an understanding of this, we can appreciate those objects of the past and understand another reason why Pounamu was so precious and valuable to Maori.

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna: My objects relate to traditional objects through the choice of materials and the context behind them, by using traditional and native stones, having a Maori philosophy, cultural narrative, and sharing those stories. I want the audience to make their own connections. If they make a cultural connection to Maori Tikanga through my work, then I achieved in building a connection. If they just enjoy the work for the craftsmanship and aesthetics, then that is great, too. They are made for everyone. I am a new, emerging artist that wants to share contemporary jewelry, my uniqueness, and identity.

How would you describe Maori contemporary jewelry? Is it different to contemporary jewelry made by non-Maori people?

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna: I am a jeweler who just so happens to be a Maori, or am I a jeweler who uses Maori taha in her work? I am who I am, and my identity and experience would naturally follow through into my work. As an emerging artist, I do not think that I have the experience for defining Maori contemporary jewelry when Maori culture is still thriving and developing. Everywhere innovations are being made, internationally and locally. I guess if there would be a difference, it would be in the context of the work, but one does not want to inhibit young indigenous contemporary artists by saying that unless they are making work within their cultural context they are less of a jeweler or artist. Object and jewelry is a vehicle through which people can share something. It just so happens I choose to share myself and my Maori identity.

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna: Maori objects, whether they are of stone, wood, or bone, usually carry a name. The names are determined by the design or the maker. Giving the object a name can explain the object’s whakapapa (genealogy) and narrate different stories or the historical significance of the piece.

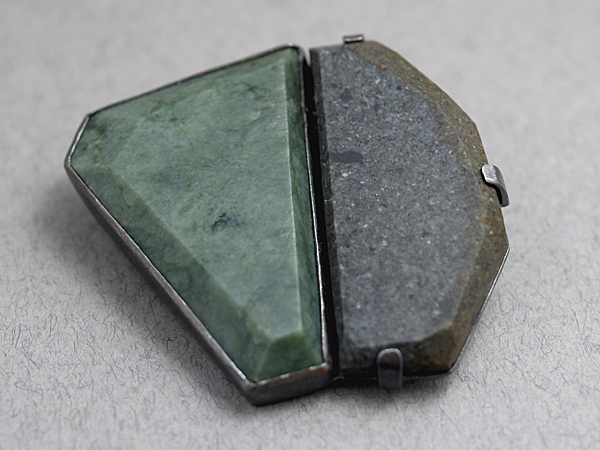

For Kohatu, each name has a meaning relevant to the object and the narrative that runs throughout this particular show. Deciding the names came after the work had been created. Each piece, therefore, determined its own identity. I let the wairua (life force) of the object and my intuitions guide me. Before physically stepping into the workshop to start creating, discussions within my community and researching Maori philosophy took place. I had a general idea of what I wanted to achieve for this show, but it wasn’t until much later in the creative process that it subconsciously manifested into Kohatu (hops). It was a natural and spiritual process.

Your work includes necklaces and brooches. Are these common types of jewelry found in Māori culture?

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna: Neckwear is common within traditional Maori culture and is often passed down through generations. Ear pendants are also a common traditional form of Maori adornment. Brooches, however, are not a traditional form of Maori adornment, although there are cloak pins often crafted from bone to clasp and pin cloaks together.

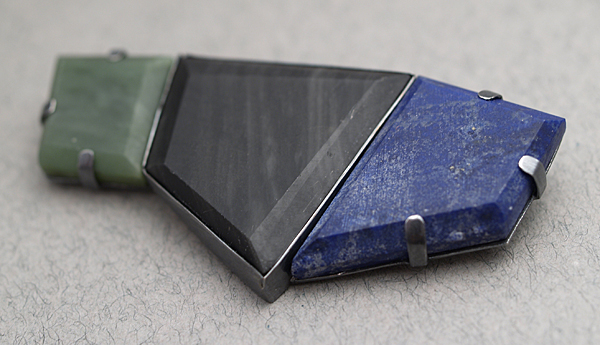

I choose to make brooch pieces as I feel that within their function I am able to more widely share the work to a diverse audience, therefore combining two cultures through function and form. Brooches are also a great way to show the different qualities of the materials and narrative. These brooches are intended to be worn, but they also function as a framed art piece where they can be viewed and enjoyed like a painting.

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna: Most of the stones in my jewelry are native with the exception of lapis lazuli, which I have used to acknowledge the Native American people whose cultural connection to their whenua (land) is similar to the Maori. It has been said that lapis lazuli has spiritual qualities in bringing harmony to relationships.

Stones used by Maori consisted of obsidian, greywacke, serpentine, argillite and sandstone, and they were used for practical means as well as ornamentation. For example, obsidian was used as flints or to cut, and greywacke was heated and used to cook food or boil water. Pounamu or “New Zealand jade,” however, does hold a more significant meaning. It is beautiful, cherished, and sacred. Pounamu pieces are often gifted to those with high status or significance within a community. I present here a famous whakatauki (Maori proverb) showing the great admiration for pounamu and its significance: “Ahakoa he iti he pounamu.” This translates to “Although it is small, it is greenstone,” using the word Pounamu as a metaphor for something precious.

Keri-Mei Zagrobelna: I feel that by using European techniques, I can connect with cultures other than my own, in a visual and technical sense drawing them into my work. I feel that I can help enhance and grow my culture by applying the use of different techniques and aesthetics and appeal to a broader audience. At the moment, I see a gap in the contemporary jewelry field for Maori jewelers, despite the presence of some notable jewelers who use and reference taha Maori. This offers an opportunity for a Maori jeweler to contribute to the field. I hope that through my actions as a new emerging artist, I can create a new way and another means of understanding cultural uniqueness and diversity. I seek to build cross-cultural communications and interpersonal relationships through the language of object and jewelry art.

Thank you.