There are so many kinds of collectors in the arts—this is also the case with art jewelry, and Claartje Keur was a special kind. She wasn’t known internationally, but she was loved and appreciated in the Dutch jewelry community. Her passion for jewelry went beyond the private—she really wanted to stimulate makers by offering them opportunities to make and sell new work.

The beginnings

Keur studied at a technical university where she became acquainted with photography. For many years she worked as a professional photographer, often working in series of photographs that formed a collection of images. The passing of time, and the idea of proving you had been somewhere, played a role in these photographs. In the late 1970s she came in contact with art jewelry by chance and was immediately attracted by its quirky character. Yet she only started collecting about 10 years later, when Dutch jewelry was liberated from the formal and material taboos that had been imposed on it since the late 1960s. In the 80s, a new generation of jewelry artists entered the scene, young people who were not afraid to distance themselves from the Dutch formalism of the pioneers of contemporary jewelry and who were interested in other ideas, including working with precious materials, stones, and old craft techniques. Keur started visiting the Dutch jewelry galleries regularly and would come to exhibition openings with her camera always in tow to make photos of the artists and visitors.

Keur’s first acquisition was four pieces at once, by the Dutch jewelry artists Annelies Planteijdt, Jacomijn van der Donk, Peggy Bannenberg, and Laura Bakker. These pieces were all made of metals: gold, silver, and copper. At this stage Keur made the important decision to collect only necklaces. She wanted to wear her jewelry and she liked the position of the necklace on the body, close to the head. Besides that, she was fascinated with the circle, an infinite form in which elements repeat themselves. So it is understandable that pendants are less common in her collection.[1]

Soon she also became interested in conceptual jewelry by artists such as Gijs Bakker, Dinie Besems, and Marcel Wanders. The Chalk Chain (1993), by Besems, for instance, actually consists of two parts, a double string necklace of chalk beads and a silver chain with a silver chalk pendant. When worn, the white chalk beads leave traces on your clothes. Keur made a self-portrait wearing this chain; it shows a black dress with clear traces of the white chalk.

A multifaceted approach to collecting

In the Netherlands at the end of the 1990s, there was an interest in fine artists making jewelry, and Keur enthusiastically participated by approaching well-known fine artists, whom she commissioned to make a necklace for her. Her collection contains unique jewelry pieces by famous Dutch fine artists such as Maria Roosen (a big blue glass eye on a black string), Helen Frik (a simple thick pink woolen thread with six small gold, silver, Perspex, and coral pendants attached to it), and Carel Visser (a necklace consisting of eight cow horns joined by hinges).

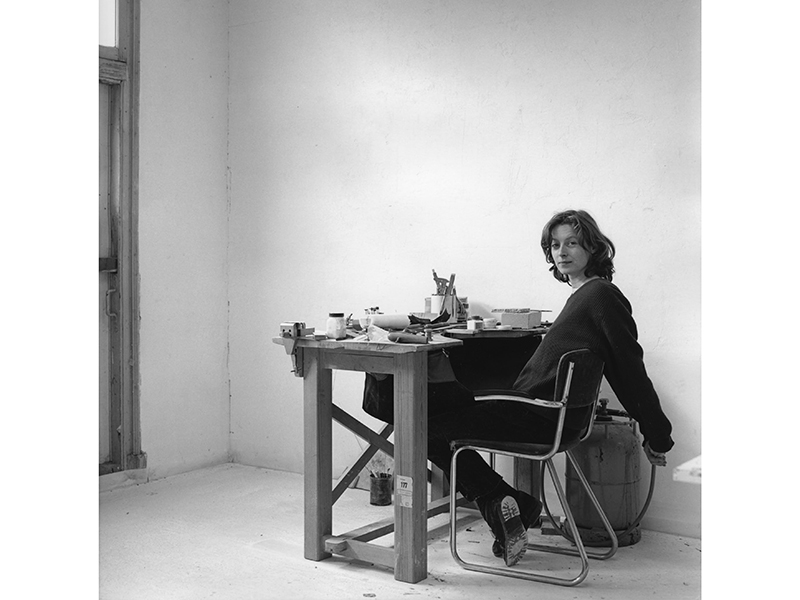

Other considerations also played a role in Keur’s approach to collecting: she was interested in having as many different materials as possible, and as many artists as possible, although she kept her purchases to only Dutch artists, or artists who had studied at a Dutch academy and lived in the Netherlands. Because she was curious and wanted to know everything about the jewelry, she made appointments with the artists, took her camera, and made daylight portraits of them in their studios. These sessions gave her the opportunity to talk with the artists and hear more about their reasons and ideas, material choices, and other stories. In 1998, Keur organized an exhibition of her collection of necklaces, combined with studio portraits. These were exhibited in the domed hall of the Arnhem Museum—in a circle. In 2014 Chain Reactions, a second exhibition of her collection that also included portraits, followed, held at CODA Museum Apeldoorn.

Greetings from jewelryland

The interaction with artists was vital for Keur. Collecting was not just about adding more pieces to her collection and wearing them; rather, she wanted to give something back to the artists. Making postcards of self-portraits wearing a necklace in an urban environment was a way to connect with artists. She sent these to the artists to show she was actually wearing the piece, and as a sign of appreciation. These cards with the text “groeten uit sieradenland” (greetings from jewelryland) were funny, if not to say deliberately clumsy. Passersby walk through the frame, sometimes right behind her.

Her torn umbrella has just been caught by the wind. A bicycle handlebar fills the foreground of the photo.

Her hair is tangled by the wind, she carries a coat on her arm, or holds an open backpack in front of her. Keur made the photos with a camera with a self-timer, which obviously influenced her position, the position of the camera (usually placed on a piece of street furniture), and the time she had to snap the photo. And yet this is the story she wanted to tell: that jewelry was part of her daily life.

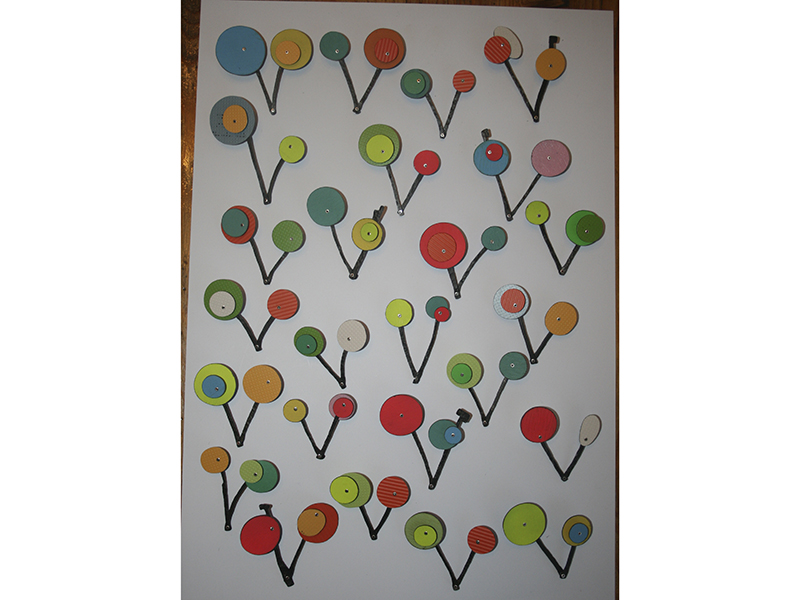

Another way of stimulating artists was by taking patronage seriously. Between 2000 and 2010 she organized a yearly Sieraden Salon (Jewelry Salon) at her place. For these occasions, she invited an established artist to make a necklace for her; this artist was asked to propose a young colleague, who was also commissioned to make a necklace. Besides this, both artists were asked to design a smaller object, in an edition of 10, to sell to the guests invited to the Salon.

Subsequently, in the period 2005–2014, Keur organized a similar project called Jewelry with a Story, for CODA. As always, she had clearly defined ideas about the project and the course it should take. The museum allowed her to make her own choices and trusted that each project would lead to an interesting and unique result. One artist per year was invited to design a necklace for a historical, contemporary, or fictional person. The resulting pieces were intended for the museum collection. Each artist also produced a series of multiples of 25 brooches to sell in the museum shop. Keur supervised the project and visited the artists regularly to discuss the work in progress. Jewelry artists such as Stephanie Jendis, Liesbet Bussche, Ineke Heerkens, and Réka Fekete were invited for this project. Fekete’s 2013 proposal was to make a necklace for the squatted house Langgewagt (in English: Long awaited), in the center of Amsterdam, where she lived and had her first studio. Although Langgewagt was not a person, Keur didn’t see a problem. After all, the way Fekete talked about the house, with its different shifted layers, and the gratitude she showed to the place was not far different from the love and dedication one can have for a person.

Claartje Keur has left her mark on the Dutch jewelry landscape. She was a special collector—a collector with a story. Unfortunately, once again the Dutch jewelry scene has to say goodbye to a striking and beloved person.

[1] See: Liesbeth den Besten, “Enkele gedachten bij een verzameling colliers,” in ‘k Zou zo graag een ketting rijgen—Claartje Keur’s collectie colliers & haar portretten van de makers, Museum voor Moderne Kunst Arnhem, 1998.