Tereza Seabra, the owner of Tereza Seabra Gallery, has had a long and unique role within the contemporary jewelry field, from her time in New York to her role in heading the jewelry department at Ar.Co (Center for Art and Visual Communication), in Lisbon. This interview examines the evolution of her career and her expertise.

Melis Agabigum: Please begin by telling AJF’s readers a little bit about yourself.

Tereza Seabra: Since I was a little girl, I’ve had an attraction for jewelry—I loved to collect small objects, little stones, seeds, pieces of everything that, in my imagination, I would turn into “jewels.” I remember one day I was at the table playing with a small box filled with these wonders and my father scolded me severely.

In 1962 I attended the painting course at the Fine Art School, always maintaining my desire to learn jewelry. At the time, Portugal was a gray and backward country locked inside a dictatorship, without any opportunity for schooling in this area. The only alternative was to be accepted in a traditional workshop and learn from a master, but the fact that these workshops were at the time small family nuclei, where mastery was passed through the generations, made it impossible to get in.

Not ready to give up on my dream, with the little means I had, I dedicated myself to enameling work in a small shared studio.

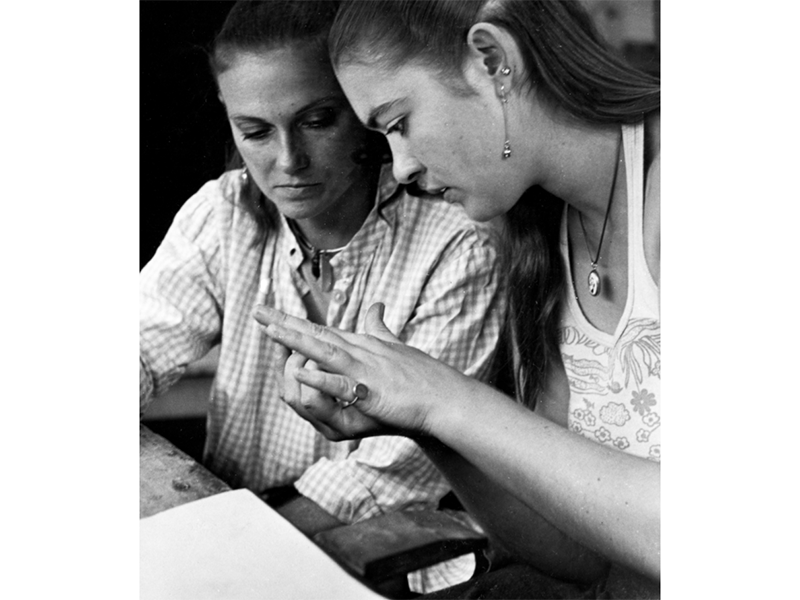

For personal reasons, in 1969 I was living in New York, where the opportunity to study jewelry was vast. By mere chance I chose a course at the Art Institute of America, led by Thomas Gentille, and later, when he went to the 92nd Street Y, I followed him and became his assistant, in 1975.

Can you share more about your time studying at the Art Institute of America in New York? How do you compare your experiences in New York to those in Lisbon, in terms of the contemporary jewelry scene?

Tereza Seabra: When I studied jewelry in New York, under Gentille, the United States already had much experience in this area—art academies where contemporary jewelry was a regular practice, museums with collections, galleries, and a vast body of reference literature. Contemporary jewelry in America in the 60s and 70s, with various trends and marked characteristics, was different from the European. Closer to these aesthetics, with an uncluttered approach, a group of artists from various nationalities stood out. They lived in New York and were associated to Gentille—John Iverson, Lisa Spiros, Eva Eisler, and Pavel Opočenský. I was very close to these artists, so their influence was decisive in my work during that period. When I returned to Portugal, in 1978, where the education and knowledge in this area were non-existent, the invitation to found a jewelry department at Ar.Co was a challenge I took without hesitation.

I’d love to hear more about the evolution from being a student to establishing a jewelry program. What kind of invitation did you receive to start up a jewelry department at Ar.Co?

Tereza Seabra: In 1978, I was invited by the then-director and founder of Ar.Co (Center for Art and Visual Communication), Manuel Costa Cabral, to start a jewelry department. Ar.Co, an independent art school, was an alternative project founded in 1973, in opposition to the formal, conservative, and old-fashioned Fine Arts School.

The teaching of jewelry within the context of fine arts appeared for the first time in Portugal under my supervision. I remained the head of the jewelry department at Ar.Co until 2004. Teaching was grounded on a demanding technical training associated to metal and to projects of great creative freedom, but still bound to a formal approach to the jewel. With the great influx of students, the department grew and enriched its curriculum with new areas of study—drawing, art history, jewelry history, in parallel with conferences on these subjects.

There was also the beginning of the student exchange programs and the first workshops with foreign artists and professors from other renowned international academies. Gentille was one of the first guests, in 1983, and at the same time he showed his work in the first art jewelry solo exhibition at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation.

The exchange of experiences, together with the vocabularies of other forms of creative expression, influenced the restructuring of the department, giving priority to the analysis of the working process and to personal experience, and not so much to the jewel as a final product. The jewel gradually lost its ornamental and merely decorative perspective, and became more experimental and conceptual. Boundaries with the fine arts became increasingly thin once the teaching became interdisciplinary.

Precious metals went from a representation of social status to a simple means of communicating the ideas and concepts that the artist wishes to transmit, together with new materials used without hierarchical distinction with the same purpose. The technical virtuosity inherent to the so-called noble metals gradually took second stage. New materials challenged the research of new technologies, giving the jewel new visual and contextual aspects, letting go of its formal side.

“All materials are precious if we know how to reveal their soul, one should never use one material when you can use another one. Because only one will work.” This saying by Thomas Gentille stayed with me, both in my teaching experience and in my work as an artist.

Maker, academic, curator, gallerist, etc.—do you feel that any of these titles, as applied to you, has taken precedence over the others?

Tereza Seabra: None of these definitions takes precedence over the others as far as I’m concerned. They’re all interconnected and complementary. I would add another one, as relevant as the others—that of collector.

It’s interesting that you add “collector” to these designations because gallerists are definitely collectors of a sort, whether it be collecting work to display for a specific exhibition or as a means of representation, among other things. Has there been a piece of jewelry in your collection that you are, or were, most excited about acquiring for your collection? If so, can you tell me a little more about it?

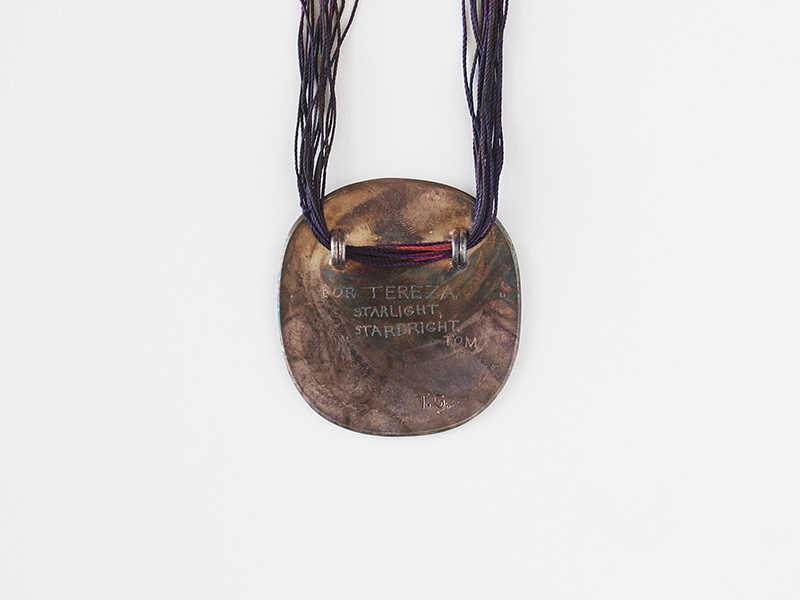

Tereza Seabra: I began to collect jewelry when I was still a student in the 70s. I have no words to describe the emotion I felt when Thomas Gentille offered me one of his pieces. Later, when I left New York, he gave me other works. Among them was one of the first brooches made with his famous eggshell technique, which he had begun to explore and which he still kept secret.

At first, my collection grew without a defined method. Choices depended solely on the wish to wear certain jewels from this or that artist. A jewel exchanged with a colleague, another from a renowned artist, and sometimes works made by my students that they gave to me when I praised them. We could call it the “collection of affections.”

As the collection started to grow, other criteria emerged and I felt the need to fill spaces that defined trajectories, either through the evolution of the same artist’s career, or by the transformation of the jewel in itself throughout time. At present the collection has 170 pieces.

For sentimental reasons I would highlight A Corrente para Tereza (Chain for Tereza), a project by Cristina Filipe. The chain is a tribute that was paid to me in 2004 when I left the position of director of the jewelry department at Ar.Co. It’s made up of 63 individual pieces, in a circle, produced by national and international jewelers, students and ex-students, professors and ex-professors, colleagues, friends, and admirers.[1] This work was publicly shown in the Ponto de Encontro/Meeting Point(s): 25 Years of Interventions at the Jewelry Department of Ar.Co exhibition, which was held at the Modern Art Center of the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in 2004.

My intention is to show the collection to the public at an institution, together with the publication of a catalog. Unfortunately, in spite of various attempts I still haven’t been able to find a sponsor. Meanwhile, I will certainly continue to enrich the collection with new pieces.

What led you to own a gallery? And can you tell us about the gallery itself?

Tereza Seabra: A few years after the founding of the jewelry department at Ar.Co, and in spite of the fact that contemporary jewelry in Portugal was timidly taking its first steps, it seemed inevitable to me to create a space for its dissemination. That’s how Artefacto3 came about. Founded in 1983, it was a pioneer in Portugal. In 1993, it became Tereza Seabra Gallery – Studio Jewelry, exclusively under my management.

From the beginning, the main purpose of the gallery/workshop was to give to the first generation of Portuguese jewelers, trained at Arco, the opportunity to show their work. It was intended to help spread this new form of artistic expression, to let it be known in Portugal, where contemporary jewelry was virtually unknown. The intention was also to create a discourse among them, with the general public and with internationally renowned artists who were also represented by the gallery, thanks to a vast contact list that had been created over the years, many of whom became and remain dear friends, as is the case with Marzee.

Now the gallery represents approximately 50 national and international artists in a 100-square-meter exhibition space that is shared with the studio. It’s located in Bairro Alto, a historical neighborhood in the heart of Lisbon that formerly had various arts and crafts workshops.

The gallery normally organizes four main group or solo shows every year, which may be thematic or not, depending on the exhibition project; there is no established rule. Besides the main shows, the gallery invites a young artist to the “panel project,” or creates partnerships between a jeweler and a fine-arts person, generating a dialogue between them.

You clearly have a very diverse programming and representation of artists in your gallery. Can you further describe your creative process when curating an exhibition?

Tereza Seabra: Successfully curating a show relies on an interesting, appealing, and innovative exhibition project. It’s essential to choose the right title and write an informative text that conveys the show’s concept and awakens the public’s curiosity. A judicious selection of the artists requires research on the works that will best fit the show, trying to bring together a balanced and cohesive group of works that function as a whole and enable a dialogue between the objects on display, which can be seen as the same vision of a concept or, by contrast, invites other interpretations and questions.

The same objectives remain from three decades ago. Besides internationally renowned artists, with whom strong ties of friendship have been established, I try to represent new promising talents (who are almost invariably later confirmed), whose work arouses my curiosity for their innovation and their use of new technologies. It’s often an intuitive choice, but I’m rarely wrong.

Intuition is so important when it comes to making, collecting, and curating. How do you know you’ve found “it” when you’re deciding to represent an artist’s work?

Tereza Seabra: Representing a new artist is always a challenge. However, I try to keep up to date through the multiple venues that today’s contemporary jewelry offers—the Schmuck and Talent events in Munich, new-graduate awards at various academies, articles by specialized critics, and so many other sources. Equally important in choosing an artist is the acceptance by the gallery’s public, although I don’t let that prevail over my choice. If I recognize talent in an artist, even if I consider the work to be less commercial, I try to explain in the best way the value of the work to a less informed public. The main prerequisite that leads to my decision, besides personal taste, is getting the feeling that this artist is adding something new to the universe of contemporary jewelry.

Are there any artists whose work you find especially inspiring or unique, and why?

Tereza Seabra: Although my work has no direct connection to any of these artists, there are three masters I cherish above all:

Thomas Gentille, my dear master, who, beyond any kind of contamination remains exceedingly original, free from a pattern of trends which are sometimes contagious in the area of jewelry, and who continues to surprise with his works.

Otto Künzli, who needs no introduction or comment and who, throughout his career, has produced iconic works filled with social criticism.

Last, but not least, Bernhard Schobinger. The multiple aspects of his vast oeuvre, closely linked to other art forms—writing, performance, sculpture, music—sometimes poetic, other times acute, bring forth in me countless deep-seated emotions.

In what ways do you see the contemporary jewelry scene in Lisbon evolving in the next five to 10 years?

Tereza Seabra: Contemporary jewelry was a latecomer to Portugal and its journey is still very short, a mere 50 years. Even though its evolution and visibility were slow in the first decades, its path, evolution, and dissemination have been clearly changing in the past 16 years, more specifically since the Ars Ornata Europeana Symposium held in Lisbon in 2004.

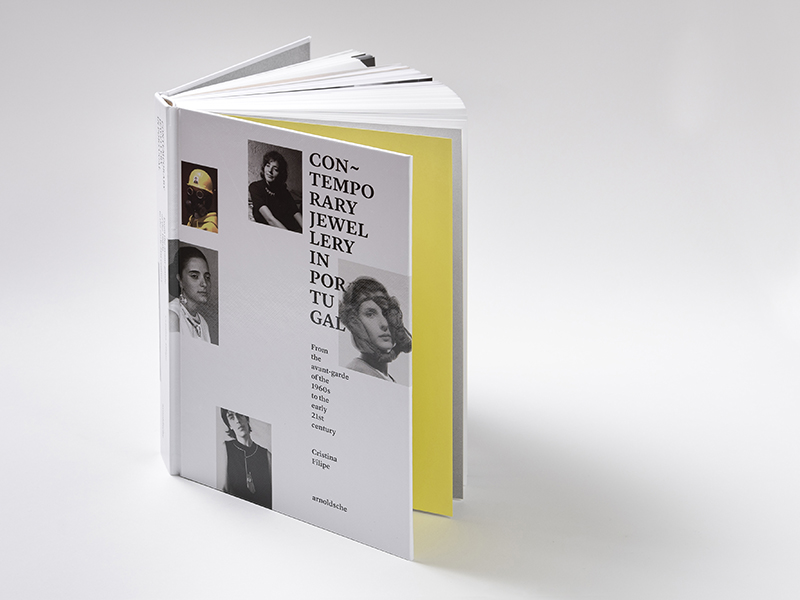

Recently, various significant events contributed to a stronger dynamic—the visit by AJF, in 2019, marked an important moment, together with the simultaneous show Summer Guests, at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation. Here, the first book on Portuguese contemporary jewelry, by Cristina Filipe, was launched, as a result of her doctoral thesis—Contemporary Jewelry Trajectories. It was published because the author received the Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant from Art Jewelry Forum in 2017.

The contemporary jewelry collection that MUDE—Museum of Design and Fashion started recently, and which has been growing, will certainly provide a strong and visible impulse to Portuguese Contemporary Jewelry. It’s the first in Portugal at a public institution.

Are there any upcoming exhibitions or events that you’re excited about?

Tereza Seabra: Every exhibition at my gallery is always a source of excitement! There are two solo shows in this year’s programing: Alena Willroth (from Germany) in September, and Lisa Walker (New Zealand) in November.

For 2021, a trio with the artists Carla Castiajo (Portugal), Marie Masson (France), and Lore Langendries (Belgium) in April; and a partnership with artists Märta Mattsson (Sweden) and Carina Shoshtary (Ireland) in June.

Still more exciting will be the Contemporary Jewelry International Biennale, organized by PIN (Portuguese Association for Contemporary Jewelry), which will be held in September 2021. In the program there are various exhibitions in galleries and museums, with the participation of national and international jewelry artists as well as students from various foreign academies. Various events are also scheduled—conferences, debates, and workshops.

Last question! If you could go back in time, what’s one piece of advice you would give yourself?

Tereza Seabra: I would say, “Do it all over again, like you did before.”

[1] See all the components at https://www.arcoabecedario.pt/entries/124?locale=pt.