A great show was expected. A major exhibition, held since 1959, with nothing to compare. By the second week of March, a total of 120 jewelry events were supposed to take place in Munich. Nothing predicted the “poetics” of an all-European pandemic, although more sensitive noses could smell gunpowder even in the United States. Then flight after flight was canceled. Galleries, too. Force majeure will remain characteristic of this year’s Schmuck.

Why do people come/go to Schmuck? For vanity, interest, greed, or any other noble purpose? The stress is on the context, on the psychological background of the period as well as personality, as much as we can comprehend it, based on the interpretation of available data.

Absolutism, claiming schemes, imperative instructions, and other similar revisionist enthusiasm are phenomena that are no longer accepted in art. People with different world views have come together, contact is made across the border of the system, seemingly unfitting things are combined, paradoxes come into being, and a paradox always has a magical nature.

The fair hall, with an expected audience of approximately 30,000 people, was the first to be canceled from the list. In addition to the main exhibitions, Schmuck and Talente, it would also have included 11 renowned galleries from all over the world—including Marzee, from the Netherlands; Platina, from Sweden; and others—a representative sales counter of specialty books, and the platform for speeches, lectures, and awards. The fair hall is always packed with attendees.

All this was canceled. This caused much frustration. Estonia had managed rather well in the preliminary round to the main expo this year. The curator, Prof. Chequita Nahar, the rector of Maastricht Academy of Fine Arts and Design, had selected 63 participants for the main exhibition, Schmuck—four of them from Estonia, more than ever before. The selected Estonian artists were Ketli Tiitsar, Nils Hint, and fresh master’s degree holders Merlin Meremaa and Erinn Michelle Cox. Of course, the number of applicants had been much higher, over 800 of them. Parallel to that success, several Estonians had searched for and found an alternative exhibition location for the week—this had been a tough task, as all the good places had been booked long ago, and spaces were expensive. However, the efforts had been worth it. This time, everything was suddenly different.

Only four book presentations took place, in the galleries in the city, one by Cristina Filipe (Portugal), another by myself (Estonia), one by Ruudt Peters (Netherlands), and one more by Ramón Puig Cuyas (Spain). This has also been a tough time for the excellent art books publishing house, Arnoldsche, which releases about 30 books a year, and published the first three on the list (Puig Cuyas’s book was put out by Sd Edicions).

The number of events changed constantly. Any possible and impossible spaces were taken for use: metro entrances, backyards, fire engines, basements, bars, embassy lobbies, not to mention available gallery spaces, showrooms, and shop or office corners—at a remarkable cost, of course. A guerilla attitude has always provided good results for drawing attention, but this time it was more restrained than in the past. Moreover, visitors never knew whether the show was open, or if the organizers had closed the space down, fearing lack of audience or the virus. Everything took place quietly.

The Pinakothek der Moderne, the museum of contemporary art and the art temple of Munich, changes its jewelry exhibit in the Rotunde every five years. After the one a decade ago by the famous artists Hermann Jünger and Otto Künzli, five years ago the exhibition was compiled by Karl Fritsch. This year it was newly curated by Hans Stofer, Mikiko Minewaki, and Alexander Blank. But the exhibition remained inaccessible to the public, with only the press allowed to visit. However, as the permanent exposition, this new curation will remain on show for five years, so it will eventually be seen.

With the closure of the Pinakothek, we also lost the opportunity to see the major reprospective show of Prof. Emeritus Robert Baines, from Melbourne. Almost everything in his jewelry leads to something else—a path to a path—and this abundance of connection is itself a kind of offering up or giving away. But we could see a few of his works at Galerie Biró/Jordanow, in the show called The Highly Honored, together with work by Lisa Walker and myself.

Although the Pinakothek der Moderne and the main exhibition in the fair hall, Schmuck, where the selection had passed a tight screening, remained closed, I did not notice any sign of fatigue or impotence in the smaller shows. The young are strong and they offer excellent and fresh creation. They’re not yet as provocative as the old badgers, but are gutsy, quirky, and funky. And intelligent conceptual jewelry is back.

Current Obsession, the fierce aficionados of jewelry from Amsterdam, had published relevant printed materials, and again, as before, called Schmuck “Munich Jewellery Week,” but the week shortened with every day and the formerly completed publications could no longer be trusted. Again—force majeure. But they were not stopped: Current Obsession has already launched a new event—Gem Z—for young jewelry artists that will span 2020–2021.

One modification was the fact that in order to simplify the choice in such a vast jewelry vortex, a separate selection of exhibitions had previously been marked in a booklet for collectors and gourmet circles, who consitute the crème de la crème in the field of jewelry art. This meant that they never attended the smaller (although good) exhibitions. And the sales crashed, as even the curators of renowned galleries complained about.

An increasing tendency is worth noticing. More and more schools are holding their own expositions. This time, the highlights were an exhibit from Seoul’s Kookmin University (planned, but eventually canceled); the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, Antwerp; PXL-MAD School of Arts, in Hasselt; and naturally the pride of the home city, Akademie der Bildenden Künste (where jewelry is under the umbrella of the fine arts). Others were dispersed among smaller exhibitions, including Shenkar college, from Tel Aviv, and Central Saint Martins, from London.

An achievement was the joint exhibition of blacksmiths from four schools, Sharing Is Caring, in an exceptionally beautiful garden—the Englischer Garten, actually a wild park in the middle of the city where local people like to spend their weekends—and there was no lack of audience there. The German Prof. Zimmermann, head of the blacksmithing course at Gothenburg Steneby College, who has also lectured at the Estonian Academy of Arts, arranged for the exhibition to take place in the Orangerie in the Englischer Garten; it isn’t normally used for contemporary art. Also included in the exhibition were the teaching staff from Southern Illinois University, in Carbondale (US), and Hereford College of Arts (UK). The simple, tall building with small windows provided space for large iron installations as well as small forged jewelry and objects. Although the exhibition had a slight underlying taste of experiment or handicraft, it fascinated many people. Iron is powerful on any level. Let us not forget the 19th-century fashion for “iron against gold” jewelry, the refined iron lace jewelry that became so popular across Europe but started in Berlin as ladies sacrificed their gold pieces in a selfless, patriotic war effort against Napoleon.

The clear ideology was also visible in the exhibition Stones—The Final Cut, at Bayerische Kunstgewerbeverein’s Kunst und Handwerk gallery, with excellent organization and design. (The curators were Elke-Helene Hügel and Wolfgang Lösche.) Stone has not always been a coherent part of a jewelry piece. There have been times when it has been a status symbol, and times—like during the middle of the last century—when it has been disregarded, used as a complementary part of the work. The other aspect has been the ethical approach. We all have heard about blood diamonds that were mined under severe conditions to finance criminality in the mining states. This is true, but also dissimulative—unless the belief is that first we win the war and then we take a look at how the battles were run…

The rise of the use of precious stones has been remarkable in contemporary jewelry during recent years. The new generation gives them a completely new face and feeling. And the organizers were brave enough to include among the 55 invited artists quite a lot of young blood—many of them from Idar-Oberstein but also from Finland and Estonia, where stone-cutting is taught on a broader level—and we do see that, as Wolfgang Lösche stated, stone alone is able to express new messages. Invited artists from Estonia were Julia Maria Künnap, Tanel Veenre, and myself. The two-story gallery was constantly crowded and there was much to see—the highest class of stone cutting art from all over the world: 321 works from 19 countries, but most of them from Idar-Oberstein, in Germany, the mecca of stone-work.

Beside renowned masters, it was interesting to also see newcomers. Catalina Brenes, with origins in Costa Rica but currently working in Italy, uses stone with disarming freedom and elegance. Luminous pieces of Carrara marmor, together with dark resin with graphite, reflecting the unique implicit emotional resonance of our time, and charged with a great empathy to the stone and its wearer, profoundly moved me. Engraved wristwatches by Reneé Pearson (born 1991), made of dark gray sandstone, will never stop—because they never tick. Pearson, who lives in New Zealand and studied in Wellington, uses local sandstone. Sihui Li tries to retain as much basalt stone as possible. She studied in Idar-Oberstein, as did the young rising star Patrícia Domingues, from Portugal, who also spent a year at the Estonian Academy of Arts and concentrates on the soul world of reconstructed stones. Her work adds something fresh to the new generation of stone cutting. Silent rock ’n’ roll? Reconstructed rock is a homogenous mass pressed together from mineral dust and binder, which enables the cutting of any configuration without any resistance from the stone. And Domingues knows how to pass on the message of vulnerability.

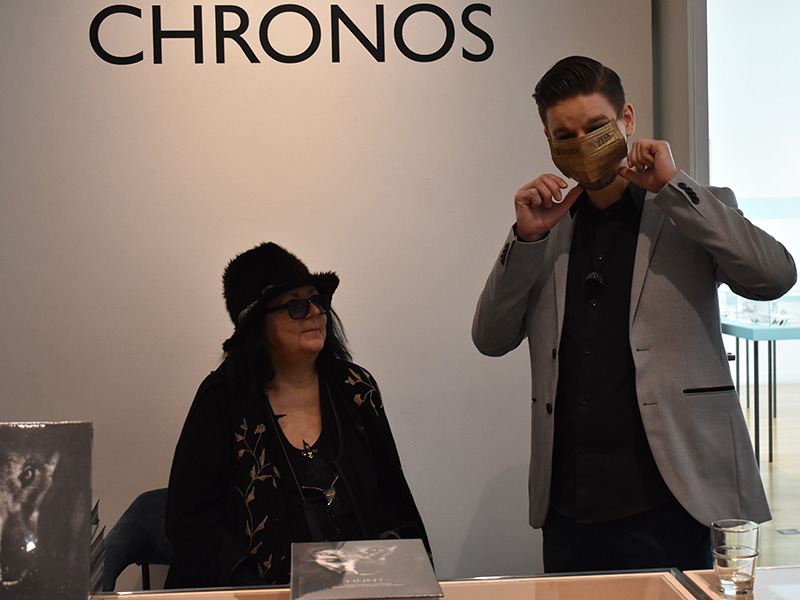

Chronos was the other crown jewel of the galleries in the city. Curated by experienced gallerist Jürgen Eickhoff/Galerie Spektrum, and displayed at Kunst and Handwerk gallery, it showed only the highest rank of masters. Seven men—Ruudt Peters, Herman Hermsen, Ramón Puig Cuyas, Graziano Vizintin, Georg Dobler, Winfried Krüger, and Jürgen Eickhoff himself—only all-stars could fulfill the well-designed space of the gallery. They were few, but there were a lot of pieces from every one of them, from different creative periods. This gave the impression, while walking through, of viewing the artists’ lives and timelines as a voyeur. These artists master the exceptional power to transform, to heal, and the potential to act upon the recipient to the highest degree of emotions. It rang with what in German is called Sehnsucht, a yearning or a wistful longing for the unknown or the mysterious.

It’s true that impact comes later, after a delay. Art enlarges our repertoire for being, but it needs time. The gifts of time and attention are the highest we can give to our colleagues and fellow travelers. The gift of giving your time is also noticed in style, profusely tendrilled as it is with trope and allusion. Once the imagination is awakened, it is procreative—through that we can give more than we were given, say more than we had to say, imagine more than we could expect.

However, as noteworthy as the objective changes in social functions of art are their consequences in the self-consciousness of the creators—in determination of their role and selection of methods. The need for self-expression and sense of mission is not different in contemporary creators than in the past, in former periods; these are the eternal qualities of the breed. But methods for perpetuating themselves are different. Artists “struggle” much more than before. They stand frantically in front of cannons, visit craters of volcanos, haunt “no-go areas” of slums—anywhere where society is bleeding—in order to erect their pole with a flag: “I was here.” However, the satisfaction of the hunger for cognitive search is probably not the main reason for the trend of showing off. On a large scale, it is fear, the characteristic impatience of the era in which art is forgotten together with its author. This year, the fear was amplified to an extent never seen before.

And the result is here. A new era has begun, namely of virtual show and sale of jewelry. Some of the exhibitions that were forced to close, like Stones, will be uploaded online later.

Still, I am convinced that it should be possible to hold a piece of jewelry, look at it closely, turn it, smell it with eyes and heart and hands, too. To touch, to try. To feel the tactility.

But jewelry is always accompanied by a certain irrationality. Roland Barthes said that jewelry is “next to nothing.” It is. Especially in wartime. Still, it was interesting to play Russian roulette in Munich this year. Although also scary, indeed. Rise—no rise. Takes place—does not take place. Flight—no flight. Etc.

I have participated in Schmuck since the last century, though not for some years. In the meanwhile, the event grew to a colossal scale and was no longer feasible for human abilities anymore. Just a buzz and rage. I share the words of a colleague: Now the good old Schmuck is back, warm and hearty, plenty of time for everything. If only the quarantine would end…

At the same time, an extremely talented Dutch-French artist, Philip Sajet, who was scheduled to come, whose works were already displayed, but who had canceled the trip due to a high workload (he has taught our students in Tallinn as well as in France), said that he has been in voluntary quarantine in his mountain village for 12 years already and is feeling very well. He travels a lot, as a visiting teacher, and masters both aspects: the general pattern of jewelry and special fragments in it. And these are constantly increasing. There is never enough time to heat the stove, do the laundry, or complete the jewelry…

This is a heavily revised version of Kadri Mälk’s original essay, published in the Estonian weekly cultural paper SIRP, on March 27, 2020. Translation by Kalle Klein and Kadri Mälk.