Christine Clark, a force of nature in the metal arts field, is known for her voluminous sculptures constructed from steel wire. Currently the head of the metals department at Oregon College of Art and Craft, Clark is also a member of Nine Gallery, an artist-run cooperative based in Portland, Oregon. She recently received the Individual Artists Fellowship Grant and the Career Opportunity Development Grant from the Oregon Arts Commision.

Olivia Shih: Not only are you a professor and the chair of the metals department at Oregon College of Art and Craft, you’re also a prolific artist whose work ranges from intricate gallery installations to large-scale public art. Talk about your background and how you found yourself here today.

Christine Clark: Actually, as of the 2018-2019 academic school year, I’ll no longer be chair of the metals department at OCAC, and will be teaching part time for the next two years. This is my gradual retirement from teaching. I’ve been teaching for the past 34 years, which is a large majority of my background. While teaching, I’ve been continually active in my studio practice. I’ve managed to secure solo shows since 1987, showing primarily sculpture. Then about 10 years ago, I began my focus on installation art.

There came a point in my career where I wanted to get into larger public works. As I began this path, I knew something had to change because it was beginning to be too difficult to teach, apply for and work on public art projects, and continue the installation work. Since I’ve been teaching for so long, the most logical thing to do was to retire from that so I can fully pursue the other two creative efforts.

Congratulations on the planned retirement from teaching! How do you currently manage to juggle all your roles? Describe what a day in your life is like.

Christine Clark: I’m a great list maker. My sketchbook is filled with words more than sketches—ideas of how, when, and why to make new things. I use my sketchbook as a guide to my goals and map out the things I need to do next. Most every moment that I’m not teaching or doing something related to OCAC, I’m in the studio. I love working so much that hours and hours can go by and I’m still enthralled in what I’m doing. It was even more difficult when I was raising my daughter; during the early years of her development, I wasn’t producing as much as I wanted. But I knew that time would be short. And now that she’s off on her own, I’m more free to work.

A day in my life in the studio begins with an early-morning yoga class (I’ve been doing yoga regularly for nearly 20 years), then I change into my holey jeans and shirts, look at my list, and get down to it. I rarely take breaks, except to stretch, drink water, eat a little, and take the dogs for a walk. Then I’m back to it. If I need to do errands, I combine as many trips as possible, including grocery shopping for dinner food. I usually quit working around 7:30 p.m. and eat a late dinner. I listen to a lot of audio books, podcasts, and music. I love working in the studio; it’s my favorite thing to do in life. Because I’m an organized person, I can squeeze in a lot in a small amount of time. Sometimes it becomes a burden, always being efficient. I try to slow down when I start feeling anxious while in the studio. It’s a great exercise in compromise and management.

During your 2014 John Michael Kohler Arts/Industry Artist Residency, you experimented with physical, emotional, and intellectual weight. Did the industrial environment of the Kohler Co. factory inspire this exploration into weight?

Christine Clark: I came up with the concept of weight before I went to Kohler. I knew I needed to find an idea that worked with the material I would be using. Cast iron is obviously heavy—so what better subject than that? I had done some experimentation with this subject before, and I wanted to challenge myself technically by making the work hollow with the appearance of solidity. The industrial environment really contributed to this concept, including on an emotional level. The workers there are some of the most genuine, hardworking, and generous people. I thought about the weight they carry, both emotionally and physically, and it inspired me to continue this path while I was there. It’s still something I think about regularly, and I’m glad I was able to create a body of work using this concept.

In your other work, you often create and play with volume through the use of linear steel wire. What inspired you to bring these two disparate elements together?

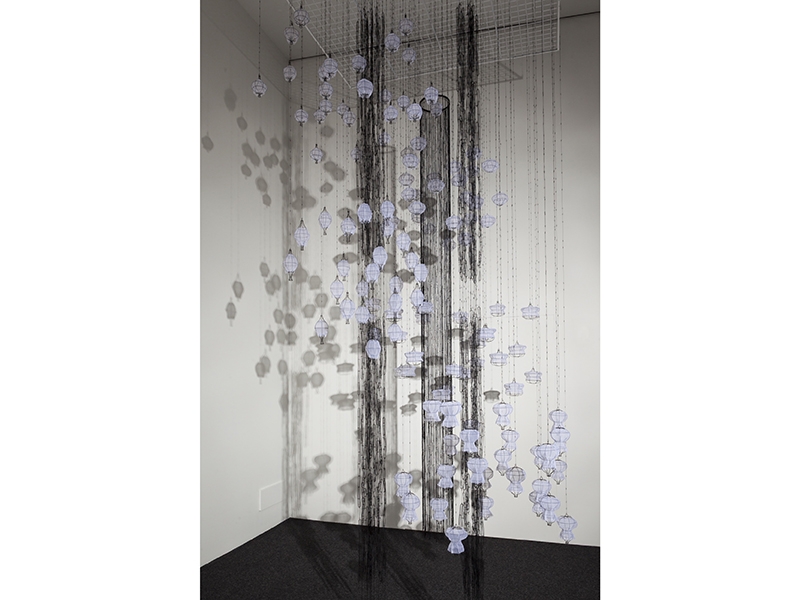

Christine Clark: I was first inspired to work with wire by the very talented Ellen Wieske. She introduced wire weaving techniques to me, and I became fascinated by it. I couldn’t help thinking about how a singular linear thing could create volume so easily. The more I played with it, the more I saw its endless potential. Then I taught myself micro torch welding, and that expanded the possibilities even more. The wire weaving techniques create volume but also an airiness that allows for lightness even within a large piece. Working with multiples of these wire forms further solidifies volume with lightness, and I can fill a space without the heaviness of something solid. Although I’ve been working with this technique for more than 15 years, I’m still not finished with it.

For you, what’s the most significant difference between creating intricate installation components and creating large-scale public art?

Christine Clark: There are a lot of similarities, including planning, looking at the space and how it fits with an idea, considering quantity and what will fill a space appropriately, reflecting on how certain materials will work in a space; and determining whether or not the project is financially feasible.

The differences are that, with my installation art, I don’t worry about whether the public will accept it or not. I do what I want, to say what I want. I’m free to experiment and explore possibilities that I wouldn’t necessarily be able to in, say, a commercial venue. I also don’t have to worry about the longevity of installation art. With public art, I need to be very aware of what the public will see and how they’ll interpret it. In thinking of concepts, I consider many things, such as the history of the site, how people used the site in the past, and who currently uses the site and how they use it, among other things. I’m extremely concerned with the longevity of materials and how they can be easily maintained. If it’s a piece that will be touched or used, I must consider how that will affect the work in the future. I have a lot less freedom but I enjoy the challenge and the notion that the work will be there for a very long time.

They are really two different approaches to making art, even though there are some similarities. I’ve been working hard on learning how to use Rhino (a 3D drawing program) and how to apply it to both my installation art and the public art. This technology has helped me immensely; I’m not sure what I did without it in the past.

Describe the thought process and labor involved in your public art project, Tribute Baskets.

Christine Clark: The first thing I did was research the history of Bainbridge Island. The first known people to inhabit the island were the Suquamish Indians. I visited a lovely Suquamish museum just off the island, and I was astounded by their skill in basket-making. The baskets were beautifully crafted, very tightly woven, some of them so tight they could hold water. The patterns were simple and elegant. These were my inspiration for the whole project. A positive concept, the baskets represent all the wonderful and necessary elements about living and life.

At first I wanted to honor these people, but after more research I realized there were other cultures that lived on the island and still do. So to honor the four major groups of people who helped found the island, I created patterns inspired by elements such as ancient runes, symbols, and patterns. The four basket patterns represent the Suquamish Indians, the Scandinavians, the Japanese, and the Filipino people.

The main structures of the sculptures were done by Jim Schmidt, a fabricator in Portland. I welded all the horizontal elements and the patterns. It was a juggling act because there are inner and outer baskets on each sculpture. Once the structure for the inner basket was delivered, I’d weld all the horizontal wires and the patterns. This was picked up and another was delivered. Then the inner baskets were welded to the structure of the outer basket. The whole thing was delivered back to me, and I welded the horizontals on the outer baskets. This back and forth happened eight times before the project was finished.

Your 2017 project, Give, is comprised of thick-walled concrete vessels suspended from the ceiling by skeletal chains. Each vessel corresponds to the varying degrees of human ability to give. Why does the concept of “giving” captivate you?

Christine Clark: I was thinking about our society, with regard to division between the classes—rich and poor. The divide seems to get larger and larger, not solely monetarily, but also in attitude. It boggles my mind that there are people who have so much—so much more than they ever need or can use. And there are so many people who are in such dire need, work so hard, or are in a situation that will always prevent them from getting ahead. The unfairness of it is so grand and so overwhelming to me that it warrants attention. I don’t usually work so politically but felt that it was time to express myself through my art. Still abstractly represented, which is my style, I said a little something that means a lot. To me, giving seems like such an easy thing to do. Why isn’t everyone giving?

Do you have any advice for emerging artists on how to cultivate a thriving art practice?

Christine Clark: Keep working. Work as hard as you can, all the time, whenever you can. Find a corner in your apartment, use your dining room table, take over your bedroom. Do what you can to make it work, but keep working, experimenting, and never stop yourself from doing something bold because you’re afraid to fail. Be resourceful and find funding. This takes time away from the studio, but it’s necessary. Apply for everything to keep yourself working and fulfilling deadlines. Find something you’re passionate about and exploit that until your ideas take you on to another new impassioned path.

What’s in store for you in the near future?

Christine Clark: I’m currently working on three projects. One is a public art project at the Everett Public Library in Everett, Washington, just north of Seattle. This will be a very large piece consisting of hundreds of elements hung in clearstory spaces along the main spine of the library. I have another project in Portland, at a park, where I’ll make sculptural seating. And the third project is a solo show at Front of House Gallery, in Portland. This will be a large installation using cast resin, fabric, handmade chain, and steel.

Have you heard or read anything stimulating recently? Can you share your finds with our readers?

Christine Clark: The graduate students I’ve worked with at OCAC were required to read The Poetics of Space, by Gaston Bachelard. Written in France in 1958, it contains some wonderfully poetic notions about space both large and small, our sense of place, nature, and a host of other concepts that wouldn’t commonly be thought of in terms of space. I’m also reading Adam Phillips’s book, One Way and Another. It’s a selection of essays that address a myriad of subjects in his very poetic, charming, and paradoxical way. I’m also reading The Places In Between, by Rory Stewart, about his walk across Afghanistan. But mostly I prefer to read books about artists—one of my all-time favorite artists to read about is Ai Wei Wei. I was lucky enough to purchase the gigantic Taschen book about him from the SFMOMA Museum Store for a song (it was the display copy), and I promptly read nearly 600 pages cover to cover. Another favorite artist is Richard Deacon and his book The Missing Part. But I read a lot of silly things, too, to get out of my head.

Thank you for your time!