Olivia Shih: You’re a contemporary jeweler, designer, writer, and curator. Where do you find the time to juggle all these roles?

Su san Cohn: I struggle with juggling all the time, often dropping a ball. Perhaps I should take circus juggling lessons, it might help keep my eye on the ball! Or simply try to say NO more often.

While I try to maintain making as my key practice, one way of working will take priority at different times. It all depends on what project I’m doing at the time. The challenge is how to bring the different perspectives together; each feeds the other.

I’m curious, is there a reason why you now spell your name Su san instead of Susan?

Su san Cohn: This is a relatively new change to my name. Su san was introduced by my two young grandchildren, a suggestion based on the fact my grandmother was Japanese, and that the gap gave my name a Japanese sensibility by highlighting the honorific “san” used in the Japanese language. I like their idea, and they’re delighted I now use their suggestion.

Your exhibition, Boring, Very Boring, recently opened on August 12 at the Anna Schwartz Gallery in Melbourne. What was your inspiration behind this body of work?

Su san Cohn: Boring is a word I have overheard so many times recently. Boring is used to describe experiences, exhibitions, objects, even people. This is boring, that work is boring, doing chores is boring, and so on. I overheard one teenager say her whole life is boring.

Boring seems to suggest people don’t want to look, while very boring suggests that someone has looked at the work/exhibition/task and chosen not to engage. I became intrigued with what people mean when they describe work as boring, what makes it boring. And I started to wonder if you could deliberately make a boring work.

This the room text for the exhibition:

“You can make with passion, you can break rules along the way, you can be inventive … but what if what you make is boring, or even worse, very boring? How can you know? What is boring? Predictable, spiritless, repetitive, trendy, bland? There is no clear code, no guideline. No matter what may be your intention, the viewer or the wearer will decide for you. And what one person may find inspiring another may think boring.

After a very long time how do you make work that is fresh? Perhaps the only way to unravel ‘boring’ is to make a body of work back to front. The starting point becomes ‘this work is boring’.”

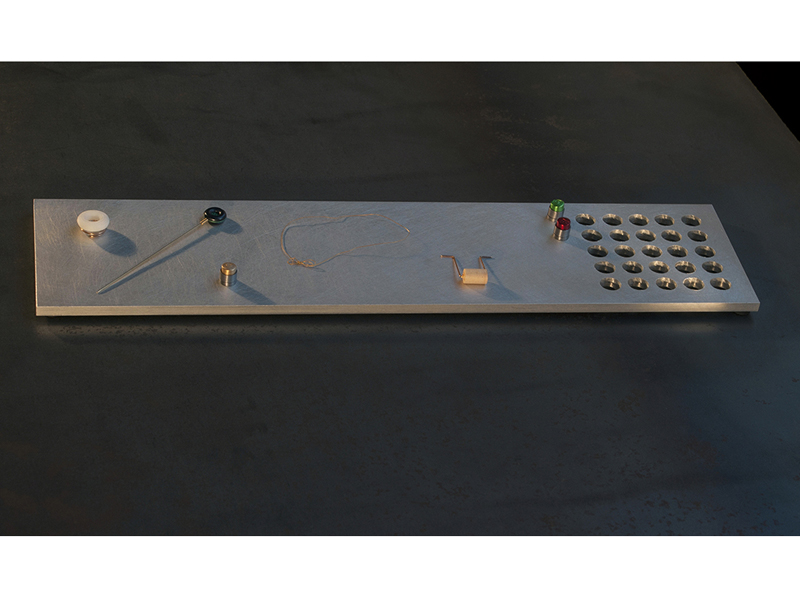

One work in the exhibition was called My Boring Collection, where I presented a group of works from other makers given to me in response to the question, “What’s your most boring work?” The result was intriguing. Once the work was removed from the intention of its maker and their workshop environment and placed in conversation with other works in a gallery context, it no longer seemed to be boring. Boring is simply subjective.

This exhibition has been the most fun exhibition I’ve done to date. People felt free to discuss the idea and the work with me openly as never before.

This summer, you helped organize a national jewelry conference in Australia to coincide with Radiant Pavilion, the Melbourne contemporary jewelry biennial. Could you tell our readers more about this conference and Radiant Pavilion?

Su san Cohn: It was winter for us in Melbourne, windy, wet, and cold!

The conference was called Making OUT. Through a program of conversations, relay interviews, diverse discussions, standard presentations, and breakout sessions, Making OUT gave us the opportunity to talk about different aspects and diverse approaches in making practices, and to engage with ways of making outside of the common discourse of contemporary jewelry and metalsmithing.

We were interested in exploring how practices of making are evolving in our ever-changing culture. We set out to explore all facets of making … unmaking, remaking, making of, making with, making for, making do, even making up. It also included a making out party on Saturday night, which, it could be said, led to an interesting shift in social dynamics in the Sunday sessions.

We attempted to mix serious with playful, informative with lighthearted, known with unknown. It was hard work to organize but worked out (made out) in the end.

Radiant Pavilion was a wild week full of over 80 exhibitions, openings, and events. I didn’t get to see all of them, almost impossible! It was a great opportunity to see the activity of contemporary jewelry and object making, to meet many different makers, to host visitors from interstate and overseas and showcase the vibrant activity of the city of Melbourne.

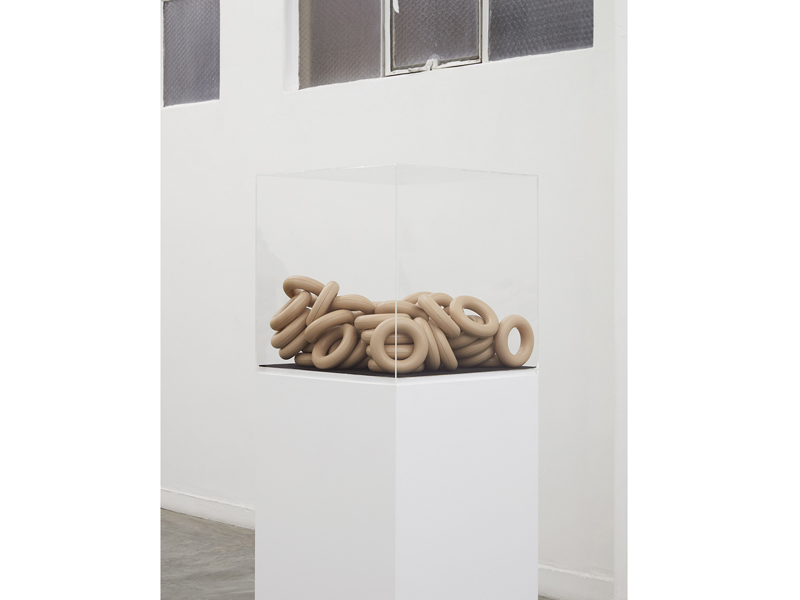

In my workshop, three of us participated with our own projects and collaborated together on one project. Needless to say, it was intensely busy, but we’re still talking to each other! Liv Boyle presented a project called New Colony, where a swarm of unidentified insects take up residence on the façade of Workshop 3000. These crafty anthropods fashion brightly colored body armor from marine micro plastics and grow pin-like stingers. Sam Mertens, in his project called Different Tastes, made a series of sake cups in stainless steel and titanium and offered them for sake tasting in a Japanese bar. My own contribution was the exhibition Boring, Very Boring.

And finally, our collaborative project, called Over and Over and Over: A Making Performance, involved programing a very good-looking, small robotic arm (Robi) to do a Scotchbrite hand-finish on earring discs. Robi was installed in our workshop street display window for the week. He kept doing it until he got bored, then he would throw away the Scotchbrite, and we would have to talk to him, re-program him, and promise him it was only for a week.

This is the second time Radiant Pavilion has been presented. Chloe Powell and Claire McArdle did an amazing job of staging the festival. It’s refreshing to see another generation take the lead in growing our contemporary jewelry and metalsmithing scene.

As a juror for the AJF Artist Award, you have the challenging task of selecting one emerging artist who encompasses potential, innovation, and individuality. What criteria will you use when sifting through applications?

Su san Cohn: I will look for fresh ideas with attention to unlying thinking, the ways of making, and what is offered to contemporary jewelry. I’ll look beyond form and materials to the reasons why something is made.

Have you noticed any recent trends among emerging contemporary jewelers?

Su san Cohn: Recycling of ideas with no knowledge of, or reference to, their precursors.

As a jeweler who incorporates new technologies into her own work, do you see an increase in the integration of technology and contemporary jewelry?

Su san Cohn: Jewelers like to play with making. There has always been a fascination with emerging technologies and new advanced materials in contemporary jewelry since the instigation of the contemporary jewelry movement in the 1960s. This follows a historical tradition in jewelry to take advantage of materials and making processes which are readily available.

Why do you think this is?

Su san Cohn: Often these preoccupations are driven by the competitiveness between universities. Object-making departments will buy the latest state-of-the-art equipment to attract students to their courses, and consequently then try to be leaders in how the technology is used.

This leads to many outcomes. Sometimes exciting work is made, but often the driving force is use of the technology rather than why the object or jewelry is being made. In addition, I’ve seen instances where the technology is so sophisticated that due to OH&S, students aren’t given direct access to the equipment, so they need to rely on technicians to make their work. Sadly, this results in a loss of making skills.

In a commentary you wrote for AJF, you mention that unlike Bernhard Schobinger, with his Holiday in Cambodia cuff, most contemporary jewelers shy away from political statements. Do you think this is still true?

Su san Cohn: I have often had intense discussion with other jewelers about whether jewelry is the place for political comment. It will be considered that jewelry should be joyful adornment. I agree with this thought. However, jewelry can become political even if it isn’t directly designed as such. It’s a worn object speaking for its wearer, and it will be the context in which it’s worn that will make jewelry political.

Can you think of a few jewelry artists who tackle political themes with panache?

Su san Cohn: Bernard Schobinger (of course), Benjamin Lignel, Roseanne Bartley, Mah Rana, Attai Chen, Shari Peters.

Finally, have you heard or read anything thought-provoking recently?

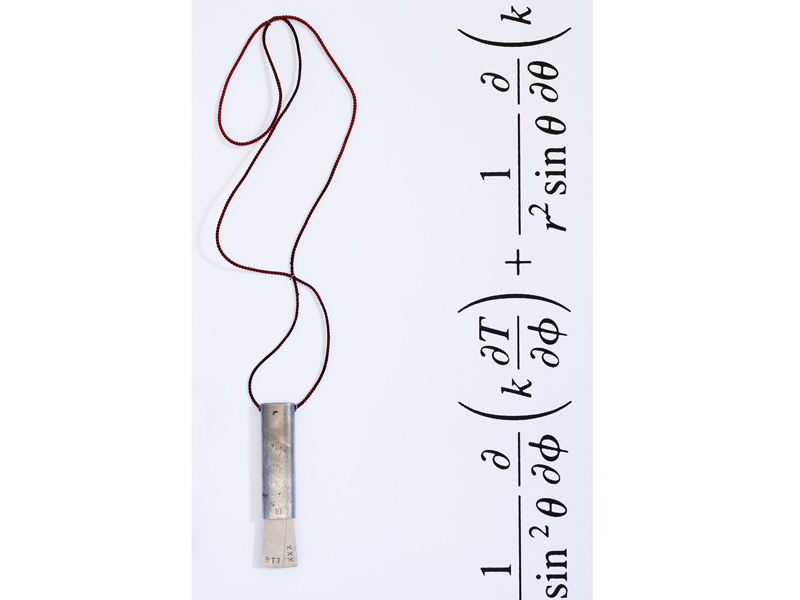

Su san Cohn: I’m currently working on a project called Meaninglessness, a performance talk with film and installation which discusses the importance of jewelry in our lives. It was instigated by the controversial jewelry law, passed by the Danish government in January 2016, which states that any assets over €2,000, including jewelry, would be confiscated from incoming asylum seekers to contribute to the cost of their upkeep.

This approach horrified me, as it did Danish citizens. Jewelry is an essential part of our lives, it speaks for us, about us. In my research in Denmark, I learned that the border guards refused to carry out searches, a discovery that has restored my faith in human beings.

On a much lighter note, I’m exploring how robotic exoskeletons could help with repetitive making—what fun!

It sounds like you have fascinating days ahead of you! Thank you!