Anya Kirvakis works with appropriated source images, from Baroque sketches to modern photographs. Her jewelry captures, deconstructs and re-creates glamour pieces as representations of representations, with all their invocation of yearning social projection. Anya’s project proposal for the Susan Beech Mid-Career Grant pushes her work into new territory: an almost subversive way of performing art jewelry where pieces sourced from film stills are recast as the main protagonists.

Adriana G. Radulescu: Congratulations on being one of the eight finalists for the newly founded 2017 Susan Beech Mid-Career Artist Grant! As the recipient of fellowships and grants in recent years, how do you see the impact of nonprofit organizations and private art patronage in supporting artists, and how has it affected your work and life?

Anya Kivarkis: Thank you! I’m happy to be in this group of finalists.

The impact of support for the arts is something that isn’t acknowledged enough. Both nonprofit organizations and private art patronage have literally been the driving mechanism of my studio practice. Having an art practice is expensive, and without the support of grants and the acquisition of work, artists’ research and ambitions would be nearly impossible to achieve.

Susan Beech has been particularly supportive. She has initiated this grant, always has kind and supportive words, is curious and engages in conversation related to work, has lent work for exhibitions, is patient, and understands the reality of balancing a studio practice with having a job and a family. It’s refreshing, and I’m grateful for all of these ways that she extends her support.

I have an immense gratitude for organizations and individuals who provide major grants for artists to take on significant projects. Last year, I received a Hallie Ford Foundation Fellowship for artists in Oregon, and its impact was truly unbelievable because I could take on ambitious projects that would otherwise have been impossible to independently fund. Those who support the arts realize that to uphold a certain quality of cultural, social, and intellectual life, they must support the time and space that artists need to make creative work.

Your grant project proposal focuses on representation of jewelry in film for your upcoming solo exhibition at Sienna Patti gallery. In 2008 you re-created jewelry objects from paparazzi images of celebrities wearing jewelry on the red carpet at the Academy Awards for the solo exhibition Vanishing Point, at Galerie Rob Koudijs. How did you become interested in re-creating/reinventing jewelry objects from source images?

Anya Kivarkis: My practice can be framed by what the art critic and historian Hal Foster characterizes as an “archival impulse” in contemporary practices. He suggests that archival artists seek to make historical information, often lost or displaced, physically present. He proposes that these artists elaborate on the found object, image, and text, and retrieve them in a gesture of alternative knowledge or counter-memory.

In my work, I have reproduced objects from many sources: historical prints by jewelry designers of the Baroque era, representations of jewelry in Baroque portrait paintings, photographs of Victorian jewelry, paparazzi photographs of celebrities wearing jewelry, contemporary fashion photography, and images from video and film stills. I look at how these representations have become surrogates for distant and recent history. For example, prints and sketches are much of what document historical Baroque jewelry because fashion shifted so quickly that pieces were continually melted down and recycled for their jewels. Due to a loss of these objects, a comprehensive documentation of the history of 17th-century jewelry isn’t possible. Because the historical originals have vanished, I’m curious about looking at the remaining traces of history, and considering what might be lost or renegotiated in our knowledge of objects as they’re increasingly understood through reproduction and the image.

In my 2007 exhibition, Blind Spot, I re-created jewelry from Dutch Baroque paintings and made those objects as fragments of what I could see, reconstructing them in perspective and cropping them where the body would intersect the object. For Vanishing Point, I moved to re-creating jewelry objects from paparazzi images of celebrities wearing jewelry on the red carpet. This was interesting to me as a different type of portrait than historical Dutch portraiture, and I loved that both sources record the desire, or the perceived accomplishment, or the progress of a certain era. Sourcing them from paparazzi photographs, I was curious about the aura of the celebrity and how these jewelry objects might achieve an arbitrary significance through their connections to famous figures. For objects from Baroque painting, the object’s affiliations are with the painter who painted them. For the Vanishing Point work, titles such as Carey Mulligan, Red Carpet 2010, View 1 reveal their brushes with significance. My jewelry from film is often from stills, and with all of my work, I reconstruct the objects as they are mediated by their source images. I re-create the film-derived objects with the crop of the frame, sequential motion, blurriness, focus, and glare built into the objects themselves. Despite being sourced from archives that reflect the height of our desires, these new jewelry objects are recoded as interrupted, backwards, or mediated versions of their original sources.

Two films you refer to in your grant proposal are Last Year at Marienbad, by Alain Resnais (1961), and To Catch a Thief, by Alfred Hitchcock (1955). Having seen them both in the past, I’m really intrigued by your selections. Why these two films, and what do they mean to you?

Anya Kivarkis: I’m interested in how both films are about points of view, and the articulation of so many perspectives. In Last Year at Marienbad, Alain Resnais constantly and deliberately shifts the point of view throughout the film to destabilize the clarity or accuracy of the narrator’s perspective. The film is constructed of many long takes with extremely slow pans of the camera across objects, characters, and spaces. The dialogue is so minimal that in some ways the film operates as both a still and moving picture. While Resnais deconstructs the cinematic image, he also in many ways fetishizes the object as the long takes enable our prolonged gaze. While the film focuses on a distant and convoluted narrative, for me it operates as a study of objects in space and motion.

Are there other films or other sources you’re considering for the exhibition?

Anya Kivarkis: There are other films that will become part of this body of work, but for now I’m focusing on just these two films for my fall exhibition with Sienna Patti.

Do you think people will need to see, or re-see, these films in order to better understand your work?

Anya Kivarkis: Not necessarily. If a viewer is interested in understanding the source and context of the work, they might be interested in accessing the appropriated origin of this work, but the work can be accessed at face value as objects.

By definition, films are moving images. Pieces of jewelry, when displayed in an exhibition, are a frame, static unless a wearer moves with them. Your Intervals of Time project, in collaboration with Mike Bray, seems a reconciliation of the two. What are you trying to convey with this project, and how did it start?

Anya Kivarkis: Mike and I work in strategically similar ways, but with different subjects, as his is film and mine is jewelry. We have always thought through one another’s projects together, and at some point the ideas felt so entangled that we decided it was time to truly collaborate.

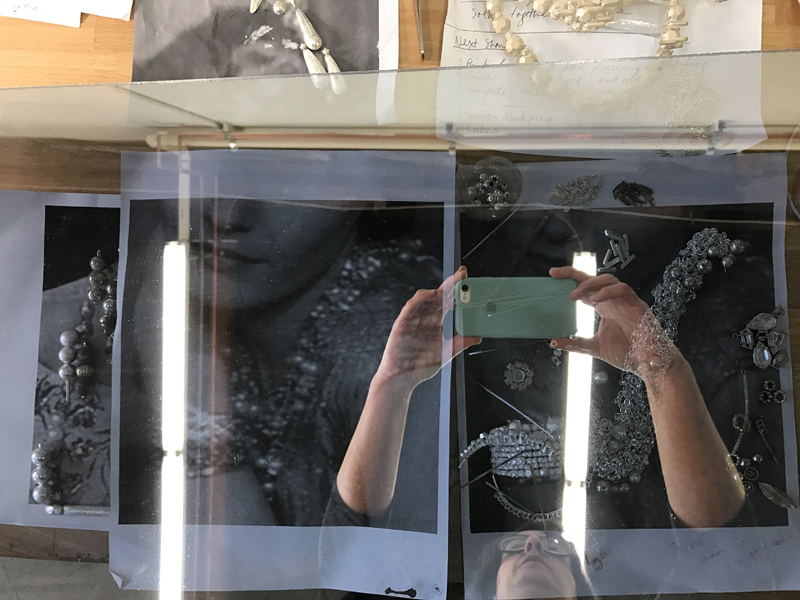

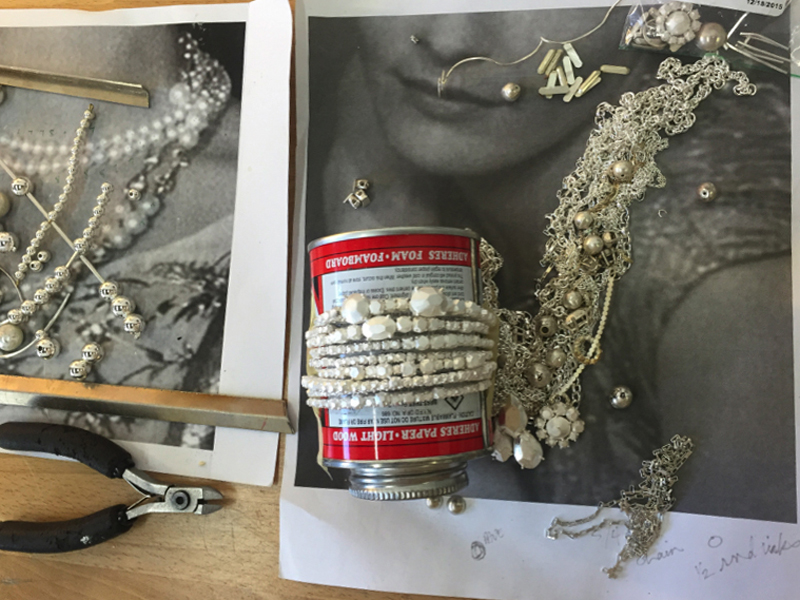

For Marble, Mirrors, Pictures, and Darkness, Mike and I wanted to examine representations of jewelry, luxury, and glamour as depicted in cinema. Since film is so absorptive for the spectator, we reconstructed jewelry objects and their partial settings from these narratives to deconstruct and perhaps neutralize the immersive nature of this media format. We often removed the character who was affiliated with the object and scene.

One scene in the film To Catch A Thief is a staged procession of characters wearing elaborate jewelry. In Intervals of Time, we installed work sourced from that scene. We re-created the time sequence of jewelry worn on the characters, based on several progressive views advancing in space, from the distanced (minute object) to the advanced (magnified object) that fills, and is cropped by, the frame of the film. We installed these objects in a procession through space, with the space between the objects approximating the succession of the jewelry in the scene. The jewelry was then mounted to two-way mirror and light stands to complicate their procession, and recession, into actual space.

Your work in the past looked at jewelry from historical moments of intense luxury consumption that ended up linked to economic crisis. How does your current work relate to your previous work and to the current times?

Anya Kivarkis: This is an interesting question that I’ve written a little bit about related to my exhibition, September Issue, in a previous AJF interview. I’ve been thinking about this a lot and researching a few images that have emerged of our current “ruling class”—images of Mar-a-Lago; Melania Trump on the cover of Vanity Fair Mexico, posing with a bowl of jewelry that she’s eating like spaghetti, for a readership in a country where almost half of the population lives in poverty; and Trump on the cover of Time magazine as “person of the year.” There’s an image in Melania Trump’s twitter feed labeled “breakfast time,” showing a bowl of intensely ripe strawberries in a highly ornamental gold bowl. I can’t help but compare this to the grotesque quality of Baroque still-life paintings that are so ripe and saturated that they’re on the brink of collapse. At the same time, a large part of me doesn’t want to inherit them as a subject, or if I take on the subject, it feels that my response would have to be extreme subversion.

There’s a significant amount of thoughtful research as a preamble to your work. What role does research play in your creative process? What do you wish you could do research on?

Anya Kivarkis: Sometimes I have an inkling of an idea, and research often helps me deepen and solidify my thoughts. Sometimes I’m seeking an answer that’s too clear and predetermined, but in reality research opens up a more speculative path.

Reading and searching in archives of history almost always triggers possibilities for my studio work. My proposal for the Susan Beech grant included research at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. I want the opportunity to delve into their archives and think about the historical decorative objects and deep storage/archiving methods of these collections. I’ve always wanted the opportunity to study decorative art collections and archives within a museum context and use that research as the subject of a body of new work.

For example, it became clear to me in watching Last Year at Marienbad that the photographed images that I sourced for my prior exhibition, September Issue, were related. Vogue’s photographer, Steven Meisel, seemed to be thoroughly informed by the film Last Year at Marienbad for his Paris Je T’Aime photo shoot. I’m interested in researching these stylistic connections and resurgences throughout history, and mapping their connections through archival museum research. Coco Chanel created the costuming for the film Last Year at Marienbad, and I’m interested in specifically researching archives of her work at MoMA.

Your work is mostly monochromatic. Why, and what does that mean in your work?

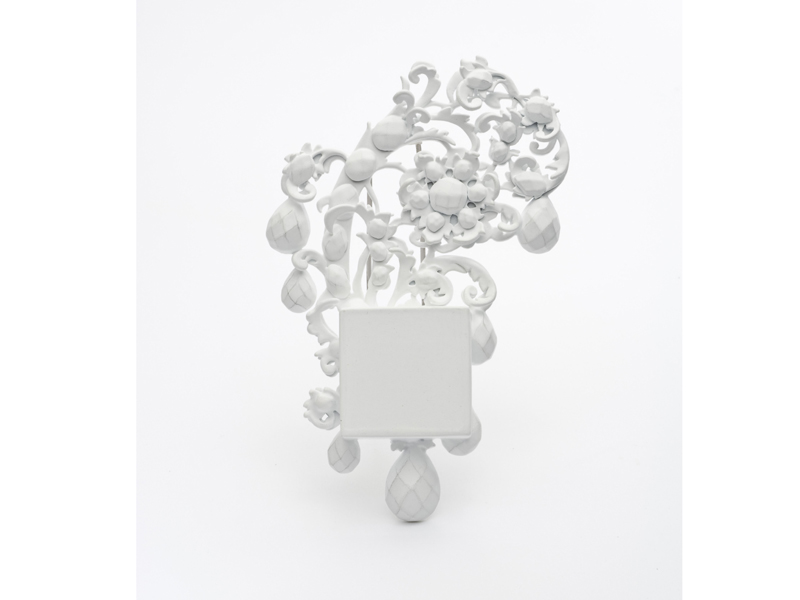

Anya Kivarkis: Initially, laminating ornamental forms with whiteness was a way for me to cancel ornamentation with blankness. The reproductions I made were sourced from prints/drawings of Baroque jewelry, and the physical objects were mediated by the reality of the images I was sourcing. In translating these sketches into objects, I painted their surfaces matte and paper-white, with steel-gray burnished marks to articulate the drawn lines of their sources.

In all of my reproductions, I carve and fabricate each jewel out of metal, because I want the copy to have the imperfection of the hand and for the piece to be “crafted,” a presumed authentic and adoring act. In later work, I gave the surfaces a sandblasted, industrial surface to make the forms blank and conflicted, almost to camouflage the care taken to produce them, as if they had been industrially made. I’m interested in how these constructed replicas can become dead objects, with homogeneous and featureless surfaces that are incapable of achieving the convincing depth that real things possess. I’m drawn to the agency of crafting approximations of objects that allows me to question “realness,” by fabricating things that look and feel hyper-real, or simultaneously alive and dead.

Sienna Patti, in Lennox, Massachusetts, and Galerie Rob Koudijs, in Amsterdam, represent your work. How did you develop your relationship with these two galleries? Having had solo exhibitions at both galleries, do you see any differences in how the public reacts to your work?

Anya Kivarkis: As a preface to any of these associations, Jamie Bennett and Myra Mimlitsch-Gray at my alma mater, SUNY New Paltz, were incredibly challenging, rigorous, supportive, and connective professors. With Sienna Patti, I sent her a postcard from my MFA thesis exhibition at SUNY New Paltz in 2004 and applied to her Emerging Artists Award. She curated me into an Emerging Jewelers exhibition and awarded me the Emerging Artist Award in 2006, which then gave me a solo exhibition titled Blind Spot in 2007. After that, Sienna represented my work.

Rob Koudijs became aware of my work when I was in Schmuck in 2007. He asked me to send him a box of work, and then invited me to mount a solo exhibition titled Vanishing Point in 2008. After that, he also began representing my work.

Both of these galleries have been tremendously supportive, and I’m entirely grateful that these two galleries have been the ones to represent my work. I’m not sure that I can accurately characterize the reaction of the public.

Besides being a working artist, you’ve been teaching at the University of Oregon in Eugene, Oregon, where you’re currently an associate professor and the area head of jewelry and metalsmithing. And you lecture, curate, critique, and moderate. How do you balance your time? What keeps you determined to do it all?

Anya Kivarkis: This is a good question, and I’m glad you ask because as an artist, educator, and mother, I’m in a unique position to address it. I’m the kind of person who thrives while being engaged in a wide range of ways. At the same time, a major source of joy for me is when I’m connected to my studio practice and research. Finding a good balance of output or external engagements like lecturing and moderating, and input like research for studio practice and research, is critically important. I almost always want to say yes to invitations, but now my time is exceedingly divided. My teaching position at the University of Oregon splits me between three areas of expected activity: teaching, my creative research, and service. As a mother balancing these expectations with the responsibilities of raising a child, I’m overwhelmed and at the same time determined. I’m absolutely committed to teaching and service, yet my creative practice is what originally brought me to a teaching position. I love that I have the opportunity to deeply engage in conversations with students about their studio practices. I wholly believe in the service of supporting my students, university, and peers, because bolstering the community and advancing the field is central to my concerns as an artist and educator. At the same time, my service burdens and the distractions from my studio practice are extreme. I thrive on delving into my studio research, so I’m finding ways to say yes to what is dearest to me.

Going back to films and research—any films, music, lectures, books, articles, exhibitions, news, travels, etc., that have inspired you, are relevant to your work, or have triggered your interest recently?

Anya Kivarkis: I recently read an interview with Helen Molesworth and Miwon Kwon about Documents magazine in the Vancouver-based magazine Fillip. When Molesworth and Kwon completed school and moved to New York, they created Documents, which was an interdisciplinary, thematic art publication that ran for only 23 issues, produced from 1992 to 2004. It’s a difficult publication to find because it’s rarely in library archives or accessible online, but I discovered that the University of Oregon here in Eugene has all of its archives! I want to dig into this because I’m so drawn to the thinking of both Molesworth and Kwon.

Thank you!