It is universally acknowledged that contemporary jewelry subverted completely the “hierarchy of materials”[1] giving voice to a new form of narrativity from paper, plastic, aluminum, and countless elements of everyday use. It is precisely from elements of everyday use like dishware and aged tins and boxes (both mass-products forms of collective patrimony) that Anna Talbot and Caroline Slotte give life to their artistic practice by transforming them into multilayered, precious landscapes.

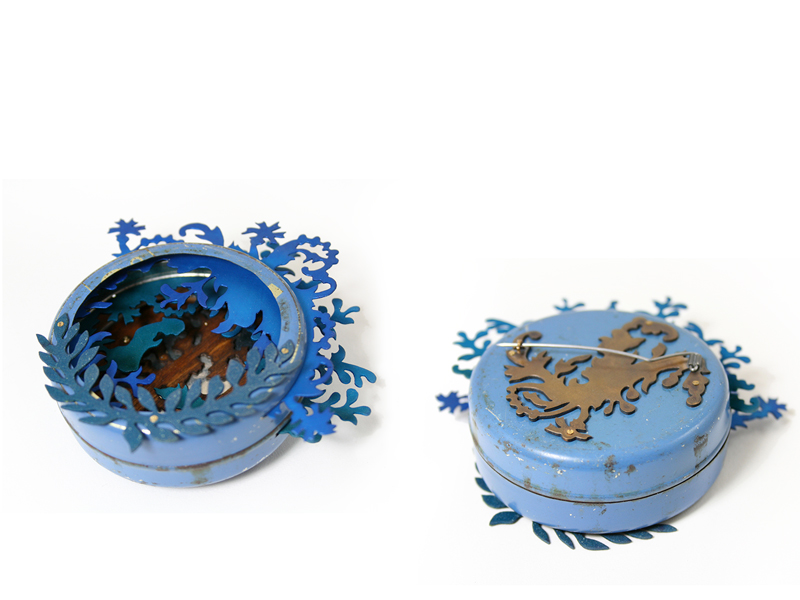

Caroline Slotte’s work consists of a series of china blue decorated plates that are cut, carved, and layered one into another in order to “reveal a multi-layered image faintly reminiscent of certain kinds of theatrical scenery.”[2] Anna Talbot’s Blue Wolf brooch is a built-up scene set in a whimsical blue forest.

“My jewellery is inspired by fairy tales, nursery rhymes, songs and stories. Wolves, deer, trees, forests and Little Red Riding Hood are all central elements in my universe, but they don’t necessarily stick to their traditional places. I want to tell a story through characters, colours and materials, and I want people to keep inventing new tales inspired by my jewellery,” says Anna Talbot about her work. “The size makes you aware of wearing the pieces at all times; they demand both space and attention. My jewellery can be hung on a wall or worn on a body. The piece becomes a picture you can carry with you.”[3]

Talbot’s Blue Wolf brooch reminds me of fairy tales by both the Brothers Grimm and Charles Perrault, yet it also weaves another kind of story. Once worn, the brooch, raised up from a common ground of fantastic tales, becomes charged with private values by acquiring a new layer of memory—that of the wearer. In this new landscape, reconfigured from explicit fairy tale references and implicit personal (hi)stories, memory is put on a theatrical stage.

In contrast to Talbot’s work, Slotte’s Multiple Landscapes have a more appropriative, and indirect, relationship to the vernacular lore of the oral and written common heritage of fairy tales. They are made from the Finnish dinner service Maisema (Landscape) manufactured by the Finnish company Arabia from 1882–1975. The floral, pastoral motifs, derived directly from popular Chinese landscapes used in English dinnerware during the 19th and 20th centuries, suddenly became a mass product in Finland, to the point of being considered typically Finnish during the 60s.[4]

The ceramic and stoneware production that started in England at the end of the 18th century as a longing for exoticism and a challenge to Chinese porcelain thus became a mass product. And the fantastic imagery soon appeared on everyday plates in most European countries. With Slotte, the “typical” Finnish blue landscape is now stacked, cut in the middle section, carved, and sharpened, and the result is another, magical landscape.

I would like to conclude by highlighting a fundamental aspect of these artworks: They both reference the landscape, one of the most common Western pictural genres. Considered for centuries only as background material, landscapes became a worthy stand-alone subject for painters during the 17th century, especially in the Netherlands.[5]

Landscape plays a leading role in the scenes of both Slotte and Talbot’s works. Whether we choose to wear Anna Talbot’s brooch or to hang it on the wall, whether we look carefully to a Landscape Multiple by Caroline Slotte, these layers of marvels and memories convey both a pictorial fascination and an intimate charm, as a landscape always does, activated here by the depth of field created by the stacked elements.

That simple device is what it takes to usher a common patrimony of collective memories onto a stage where they take on blurred cultural coordinates, and meet with your, my, our personal projections.

[1] Jorunn Veitberg, “Statement” in Schmuck 2014, exhibition catalogue (Munich: GHM-Gesellschaft für Handwerksmessen, 2014), 7.

[2] Amanda Fielding, “Caroline Slotte: Going Blank Again—A Review,” in Ceramics: Art and Perception, No. 84, 2011, http://carolineslotte.com/texts/.

[3] Christine Wilvers, Anna Talbot: Jewellery from Fairy Tales, interview in TLmag Norwegian Crafts, http://tlmagazine.com/anna-talbot-jewellery-from-fairy-tales/.

[4] Caroline Slotte, Second Hand Stories. Reflections on the Project, dissertation text research, February 2011. See her website, http://carolineslotte.com/.

[5] Jakob Rosenberg, Seymour Slive, and E. Ter Kuile, Dutch Art and Architecture 1600–1800 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1993), 239-284.