Susan Cummins: Can you tell us your family story? Where did you grow up and what was your childhood like? What did your parents do?

Annelies Planteijdt: I was born in Rotterdam in the Netherlands, and I grew up in Middelburg, in the southwest, not far from the sea; the sea was everywhere around. I was the firstborn of six girls. The best friends of my parents had four girls, so when we had dinner at their house or ours, there were 10 little girls, quite a feminine household.

My father was a pathologist and my mother did all kind of things, besides keeping an eye on us all. They were very much socially interested. We were a very close family and my childhood was very happy. I had my own room where I could play and “make things.”

When did you first discover you were interested in jewelry?

Annelies Planteijdt: Ever since I can remember, I have always been “making” things. At home, when I didn’t know what to do sometimes after school, my mother would say to me, “Go, make something.” I was always fascinated by jewelry, the jewelry boxes of my mother and grandmother. My other grandmother traveled a lot and always brought back, as souvenirs, jewelry of all kinds from all over the world. Then, at age 12 I started to make jewelry of silver wire and beads, and at age 15 I went to jewelry class after school. It was my mother again who discovered this course for me with Cees and Anne Mulder. At that time I wanted to study “languages” at the university, but after one year or so in the jewelry class I changed my mind and decided on jewelry. I remember my father telling me the difference between a translator and an artist. As a translator you are working with other people’s thoughts. As an artist you have to work with your own thinking. I was more attracted to the last and to the freedom it seemed to offer.

Did you study in a university program? Where did you learn to make jewelry?

Annelies Planteijdt: When I was 18 I went to the technical school for goldsmiths in Schoonhoven. After four years, one of them being a practical year at Jan Tempelman’s studio in Zutphen and Cees Mulder’s in Middelburg again, I continued at the Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. I had been longing to go there for a long time, but first wanted to learn some technical skills. To live in Amsterdam was like a dream to me. During the five years at the academy, with Onno Boekhoudt as head of the department, I met Giampaolo Babetto, who was one of the guest lecturers, and he offered me the opportunity to work in his studio for seven months. I was really happy to go to another country by myself and learn a lot from a great artist and teacher. And also to learn the language, which was still one of my fascinations. It was a great time, surrounded by art history and beautiful cities like Padua and Venice, where I went almost every week, as well as Vicenza, Milan, Turin, Bologna, Ferrara, Florence, etc. My stay in Padua is a jewel in my life.

Do you ever teach?

Annelies Planteijdt: I do not teach. I sometimes have talks with students about their work, but not as a regular teacher. I never developed it. From the beginning I was able to make a living from my work, with the help of grants from the BKVB foundation in Amsterdam, and I always preferred to put all my energy in my work, in order to keep it going. Really I just love being at home in my workshop and having all that time.

Where did your obsession with floor plans come from?

Annelies Planteijdt: I’d rather call my obsession with floor plans a fascination. Ever since I started to make my “own” work, I have been drawing in gold, or other materials. One moment I realized that the drawings were a projection of my thinking. Thinking is multidimensional. The projection of my thinking is two-dimensional (flat on a sheet of paper or a table), hanging is three-dimensional (gravity), and moving through time is four-dimensional.

Although thinking is multidimensional, my imagination of my work is two-dimensional. It only becomes three- or more dimensional on the body, in reality.

So the floor plans are in fact a reflection of my thinking, they are not the thinking itself, and they behave differently in real life. I see this everywhere around me in natural processes. Everything is built up of elementary particles, although you don’t notice the particles themselves. And their behavior is different in various circumstances or at another scale.

Your Beautiful City series has now added a Crystals investigation. Can you describe how you developed this new idea and what you are thinking about in the new series?

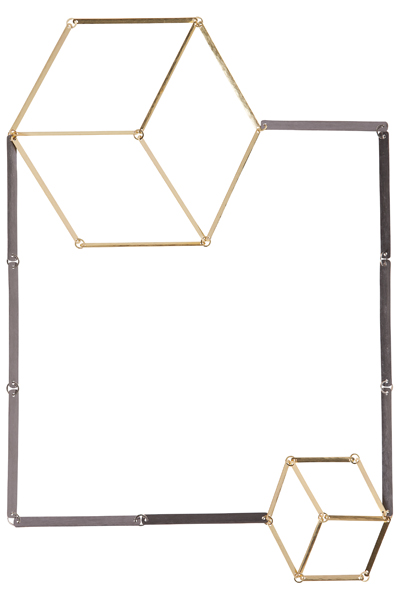

Annelies Planteijdt: The Crystals investigation emerged from earlier work. I wanted to expand, to go beyond the squares, to move out. The Crystals are not a fixed form, although you could think so. They are formed by the square they are in. The square is fixed and the Crystals adapt to the square. So the Crystals are like liquid crystals: They have the structure of a crystal, but are also liquid at the same time and circumstances. Because of this, these pieces are hard to put in their floor plan: They can move in all directions. I made relatively complex Crystals, but when they hang they fall completely in line with the squares. They appear when you put them in the floor plan, they disappear when you pick up the piece and wear it, and you can make them reappear when you put them back into the floor plan.

You can only see where the Crystals are when you look at the layers: Instead of surface there is stratification, density. Instead of being spread out they become compact in one line.

The Crystals are in a necklace what a diamond is in a ring. The square is the setting of the Crystals. They are being held by it. The Crystals are made of the same material as the floor plan—it’s just a small change in size, or color, that defines the Crystals.

You tend to use various colors on the different sections of your necklaces. How do you decide what section should be which color? Is there any significance to the choices?

Annelies Planteijdt: The choice of the colors in my pieces is made very slowly. The colored part is mostly the part that is held by the squares. There is no significance, as in symbolic meaning, in the colors. They don’t stand for anything. I choose them according to my preference and my imagination of the piece. I am looking for colors that are strong together, so they don’t lose strength or clarity opposite or next to each other. I use the pigments pure. I don’t mix them.

What do you do for fun?

Annelies Planteijdt: What I love doing for fun is having dinner with friends, or riding my bike along the river Schelde near my house (there is a beautiful bicycle path where the sea meets the river). And I am learning the Chinese language once a week, but I am not learning to speak it. I am interested in languages and challenge myself to learn about them.

There is a small place (only a few houses) on the north coast of Brittany in France where we have gone for holidays for a long time now. I always go west to the sea.

I am always dreaming about going to Amsterdam more often to visit friends, see exhibitions, and walk in town, but time flies all the time. So I find myself most of the time here at home in a very small village having time and making contacts through my work in a lot of places in the world. That is fun for me, and gives me the feeling that I am playing.

Can you recommend a book, movie, play, some music, or anything else that has struck you as worth recommending?

Annelies Planteijdt: I love reading, although I am a slow reader. What I have recently read is The Stranger by Albert Camus, Open City by Teju Cole, All That Is by James Salter, Selected Stories by Alice Munro, Monte Carlo by Peter Terrin, IJstijd (Ice Age) by Maartje Wortel, and Dagen van gras (Days of Grass) by Philip Huff.

Thank you.