Meanwhile AJF, being of the WTF persuasion, believes that the intensity of intellectual stimulation we provide should be directly proportional to the quantity of sand you are sitting on. And so I have asked some of the fiercest book consumers I know—namely, the very smart people who contribute to this website—to tell us about one book that has made a particular impression on them. Quite a superlative cast of people has kindly accepted my invitation, and I am delighted to announce the 2015 summer book tour. This is its first installment.

Book Tour: publication dates and cities of provenance

Montreuil, July 2 Benjamin Lignel Little Rock, August 2 Marion Fulk

Zürich, July 10 Monica Gaspar Oslo, August 10 André Gali

Liverpool, July 17 Stephen Knott Melbourne, August 17 Kevin Murray

Lahore, July 22 Amina Rizwan Portland, August 22 Namita Wiggers

Amstelveen, July 28 Liesbeth den Besten Seattle, August 28 Jennifer Navva Milliken

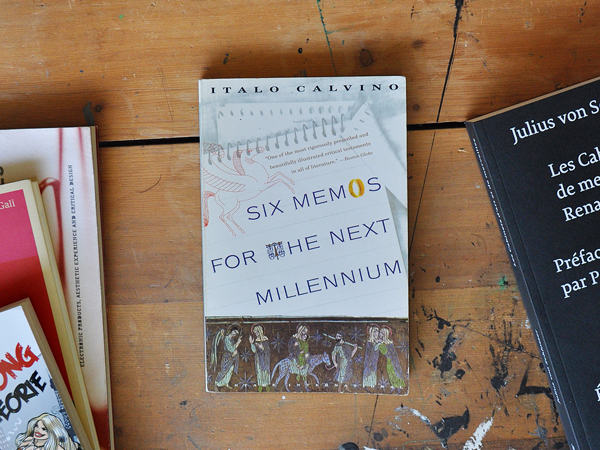

I have probably read this book seven times. I own several copies of it, in its English and Italian versions, annotated with the various pens I partnered with in the course of my reading life, before committing in 2004 to a stable, (re)productive relationship with a thin-tipped, four-color ballpoint pen of the brand Bic. (Everything from that point on is annotated in green only; go figure.)

In 1984, Italo Calvino—a lauded Italian writer, social and political commentator, editor, and translator—was invited to deliver the prestigious Charles Eliot Norton Lectures for the following year, at Harvard University. He started writing them in January 1985, and finished five of the customary six lectures by the time he was due to fly out to Harvard in September.

Those lectures focus on qualities of literature that are particularly close to Calvino’s heart: lightness, quickness, exactitude, multiplicity, and visibility. Each quality (and its antonym) is examined, and examples compared that are plucked from near and distant shores of literature. Aware of his highly educated audience, Calvino saunters back and forth through the ages, quotes in the original and gushes precisely about the use of words as a “perpetual pursuit of things, as a perpetual adjustment to their infinite variety” (lightness). He waxes lyrical about the “excitement of two simultaneous ideas” (quickness) or, case in point, about Leopardi’s “minute definition of details, in order to attain the desired degree of vagueness” (exactitude). Calvino turns reading into an adventure: he accelerates, doubles back, and digs deep for hidden syntaxic gems. He likes to tease drama out of a writer’s choice of adjectives, in a prose both exceedingly precise and digressive.

Fiction is where he goes for intense pleasure, and he means to tell us about it.

He died in September 1985, and never went to Harvard. His wife, Esther Calvino, found the five completed manuscripts on his desk “all in perfect order, in the Italian original, ready to be put in his suitcase.” This element of drama adds an exclamation point to a sense of legacy that did not escape Calvino at the time of preparing for Harvard. He conceived the memos as erudite love letters to literature that was yet to come, extolling the many ways in which he had loved the writing of the past: “My confidence in the future of literature consists in the knowledge that there are things that only literature can give us, by means specific to it.”

You, clever reader, will recognize here a claim that we have often made about our field. The Six Memos provide a lesson by example: They encourage us to acknowledge what is singular about our practice(s), and the infinite range of what our limited toolbox can produce.

In paperback.