March 19–April 16, 2015

Anna Miles Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand

Progressing from the gentle arrow beckoning me away from the cacophony of Upper Queen Street to the hidden entrance of 10/30 and the Anna Miles Gallery, I am quietly curious. Welcomed by a praying mantis with smiling eyes and forelimbs folded, green against gray, perched atop a garage door of parallel lines next to my rather randomly chosen parking space, I arrive. My goal is Symmetry Is the Work of the Devil, an emotive exhibition with an equally emotive title.

Curator Kristin D’Agostino’s journey is an interesting one. Inspired by works of kapeu/kuru[1] exhibited as part of the Wunderruma exhibition and by a visit to Fingers’s anniversary show, where a number of single earrings were on display, her contemplation began. “Have you ever stopped to wonder why you wear matching earrings but not matching bracelets? How is it that the earring was a status symbol relating to breastfeeding in one cultural context, but in another it provides tags for sexual preference? What is the origin of the earring pair?”[2]

Proceeding further, my eyes digress toward a rectangular glass cabinet marked Octavia Cook, before looking up to four steps, a peach printout, and the stairway exhibition unfolding above.

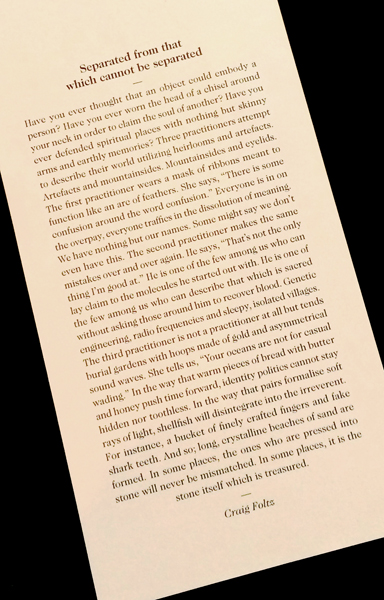

There, a narrow corridor, and a continuous flow; here, a flight of stairs and broken fragments. There, the accompanying text was placed on the wall at the end of the corridor. Here, on a postcard, it is more like an intimate introduction or an opening line. The switch from punch line to prologue gives Folz’s text an explanatory role it did not have in Opening Night; I find the decision well advised, since tonight’s vistors may not be as jewelry-versed as the previous crowd but I wish they could have experienced it as I did the first time, like a poetic quasi-epitaph.

A quick glance to the stairway exhibition unfolding above. One step at a time. Literally.

My progression from now on will be made of starts and stops. The placement of each earring behind staggered, randomly sized “modesty” panels encourages both my contemplation and a mounting desire to view the next hidden piece attached to the stairway wall.

So stepping forward, I ascend. My first: A fabulous fluffy ostrich feather work from Ilse-Marie Erl gently caresses the wooden paneled wall.

Take time. With a subtle head movement or shift of weight, left to right, the viewer can experience this evocative three-dimensional book unfolding ahead, with pieces slipping from view as they fall “behind.” They are accompanied at times by intimate and evocative captioning, provided by the makers themselves. (Neke Moa’s title: Tangi Tangi—Everyone Is Their Own Musician.)

All the pieces from the Opening Night show, bar one, are featured in this version at Anna Miles Gallery: five single earrings selected by the curator from existing work and 11 works created by jewelers responding to her invitation. There are a lot of different practices at play here, but as the story unfolds they seem to fall into place. The deft placement of certain earrings next to one another, such as Jane Dodd’s Tail and Raewyn Walsh’s Earthworm, and the conversation that ensues from managing relative scale, material, and weight on this vertical score all contribute to this exhibition’s strength. The changing light is more successful than in D’Agostino’s first show. Perhaps the tighter wall space is a contributing factor. The crisscrossing shadows and architectural shapes of the dividing boards falling across displayed works literally seem to add a third dimension to the unfolding story.

Approaching now the final step, a moment to reflect. Stairways are notoriously difficult spaces in which to exhibit. Plagued with issues of public access, (potential) conflicting eye-line dilemmas, and shifting environments, they are not an easy space to “make work.” D’Agostino’s panel system gave her an advantage (restricting sight), which she and Miles adapted with success to the stairwell environment. The show’s impact also resides in not fluffing up its simple intent—to recontextualize the earring as a solitary ornament, and leverage the absence of a “missing half”— thereby allowing a suprising amount of hidden complexity, made of layered memories, images, and words.

Then, as if by magic the final piece—Drop by Karl Fritsch—viewed in shadowless clarity, completes my ascent of the stairs. And with Foltz’s opening words drifting to mind—“Have you ever thought that an object could embody a person”[4]—I reach the final step. I will be wearing a single earring tomorrow.

INDEX IMAGE: Exhibition view, Symmetry Is the Work of the Devil, curated by Kristin d’Agostino, Anna Miles Gallery, Auckland, New Zealand, photo: courtesy of artsdiary.co.nz

[1] In Maori culture, single ear pendants known as kuru when made of pounamu (or green stone) “were highly prized and often worn by people of chiefly status. Often a kuru pounamu would be used in oratory to refer to a deceased person held in great affection. ‘Taku kuru pounamu ka makers’ (my kuru pounamu that has fallen).” Story: Pounamu—jade or greenstone, Te ara/The Encyclopia of New Zealand, http://www.teara.govt.nz/en/object/7682/kuru-ear-pendant).

The kapeu, a single ear pendant with a slight bend at the bottom, is also highly prized. It is a sign of high rank in Maori society.

[2] From Kristin d’Agostino’s curatorial pitch, as sent to Anna Miles.

[3] Kristin d’Agostino, from project abstract sent to artists, December 2014

[4] Craig Folz, Separated from that which cannot be separated, exhibition text printed on card.