Ruudt Peters, who took over the department of metals in 2004, chose the name Ädellab, which means “precious laboratory.” This is a funny name for a program whose students aren’t as concerned with using precious materials as they are with executing ideas through jewelry and bodily ornament. Karen Pontoppidan, who became professor in 2008, replaced Peters.

The Ädellab program consists of a three-year BA course and a two-year MA course. Pontoppidan has split the undergraduate program into three different categories she calls “shake,” “awake,” and “make.” During the first year, students shake up their preconceptions and preconceived ideas about jewelry and are given the tools, physically and metaphorically, to help them succeed over the next three years. In their second year, they awake to the rich and diverse creative world of the discipline by interacting with leading jewelry makers. In their third and final year, they make, creating their first significant collection of jewelry. While the program promotes an international learning environment, the courses are taught mostly in Swedish with occasional instruction in English.

The Konstfack facilities are located in a former Ericsson telephone factory that was renovated in 2004. Students describe it as being really beautiful with high ceilings and large windows. Each student has their own workbench and a table for sketching. According to Spranger:

Ädellab is comprised of several metal and jewelry workshops and a big common area where all students have an individual working desk space , which is the “heart” of the department. To work at this space is most popular because students experiment and explore a lot with different materials: deconstruct, mix, build up, sew, sketch, draw, 3D model, exchange and discard ideas, think, write, chat, contemplate, and fuck up things!

There is also a departmental kitchen. It becomes a gathering place during exams when many students spend their days and nights at the school, sharing meals and ideas.

Pontoppidan, a well-known Danish jewelry artist and former student of Otto Künzli’s, now leads the program and teaches some elective courses. She is also leaving her own mark on the program by shaking up the curriculum. Two of her courses are “Project X” and “Grim Ripper & Co.” Katrin Spranger explains:

For the Grim Ripper course, we made a field trip from Stockholm to Vienna, Austria, to experience the cult of the dead from their perspective. Other units of this course included material exploration, impromptu assignments, subject resourcing (movies, literature, etc. for inspiration), and the development of one’s self-defined “dead piece of work.” Project X was a course about a specific working method connected to problem sharing, problem solving, brain pooling, and brainstorming. Everyone was supposed to develop a body of work with the help of all course participants (with different creative backgrounds). We shared knowledge and hands-on experience. Everyone worked for a specific time for one participant and vice versa.

Workshops and critiques are another instrumental part of the program. Students were encouraged to discuss their work with their fellow students and to open themselves to constructive criticism from their peers—certainly a valuable exercise that makers too rarely have the opportunity to undertake. I was also impressed when Pontoppidan told me that none of the instructors in the program are allowed to teach full time. Rather, they are encouraged to continue making their own work.

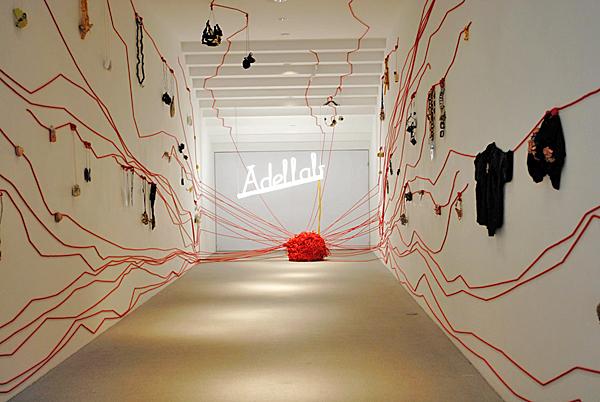

Another activity Karen Pontoppidan and Ädellab promote is participating in exhibitions, and none are more important than The State of Things. Explaining the title of the exhibition, Pontoppidan said that:

The final-year projects undertaken by exam students are not a matter of fulfilling an educational task. Rather, they demonstrate the need for individual expression that spawns creation. The artistic expression and the work of graduates cannot be understood only in terms of intrinsic logic or the desire to understand the existence or the state of things. The work was created because an artist—a human being with experiences, feelings, dreams, and failures—wanted the pieces to be.

I thought the work featured in the exhibition was incredibly conceptual and not all of the pieces were extremely wearable. Even Spranger told me that her work “is simply not commercial enough, nor wearable on a daily basis, nor pretty.” While the definition of “pretty” is culturally contingent, I would agree that most of the work on view is not pretty. However, it is not the goal of Konstfack to promote jewelry that is pretty or commercial. Pontoppidan encourages the students to use jewelry as an expression of feeling and ideas, and they have successfully done that. Most importantly, they have experimented with materials. Judging by the variety of materials on view—horsehair, needles, iron, sweet potato, sea sponge, and crude oil—they have certainly taken that brief to heart. I am also happy to say that the student work is very different from their professors. Frequently, when a professor has a strong voice, as Pontoppidan does, the voice of the students gets lost. However, this is not the case according to the evidence in The State of Things.

One gets the feeling that even after their time at Konstfack is over, the students’ bond, like the rope, is very strong. In fact, Spranger, Larsson, and Hedman all told me that many students share studio space and workshops after graduation. Even in Munich at Schmuck, the Ädellab community of students and teachers was back together. During the opening of his own exhibition at Galerie Spektrum, Ruudt Peters waved good-bye to his guests and crossed the street to join his Konstfack family for the opening in die Neue Sammlung’s lobby.