The museum is a slim black box with three floors of displays, leading up to a temporary gallery at the top with panoramic views of the old city. It was conceived by Lee Kang-Won early in her 30-year period as a diplomat’s wife, during a posting in Ethiopia. Posts in other countries served to expand the collection, which was made available to the public in 2004 at the World Jewellery Museum. Lee Kang-Won’s daughter Elaine Kim now curates the collection and her skills in graphic design contribute to the museum’s feel.

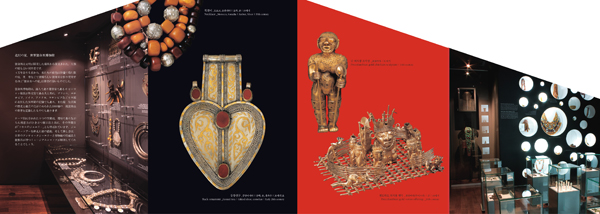

The first generic display is of bracelets and anklets, mounted in circular forms set into the black wall. Next to this is the impressive El Dorado Gallery, which at this point, I felt the museum was offering a rare glimpse into the nature of body ornament. The ‘pre-Columbian’ pieces depict the coronation ceremony at Lake Guatavita in Colombia where the king, layered with gold dust, was set adrift on a raft containing golden treasures that were then cast out into the water. If there were to be a ‘history’ of preciousness, this would be a key scene. As evoked in Voltaire’s Candide, El Dorado appealed to Europeans as a place where gold was considered to be as valueless as mud, thus inviting European adventurers who knew its true value to rescue it from oblivion.

The World Jewellery Museum braids these ethnographic scenes with more ahistorical displays of ornamental forms. After a gallery of necklaces comes the Altar of Crosses from Ethiopia. The ethnographic work continues on the next floor with a Mask Wall, which speaks more to the museum’s interest in primitivism than a history of jewelry. By contrast, the Ring Wall offers a more formal experience of jewelry. Rings are displayed in acrylic sheets hung from the ceiling like frames from a bee hive. This evokes the aestheticized view of jewelry found in institutions such as the Musee des Arts Decoratifs in Paris, where context is minimized in order to enhance the beauty of the object itself.

An immediate question on completing the tour is the nature of ‘world jewelry.’ For a visitor to Seoul, it’s strange to see very little Korean jewellery on display. The sense is that, in this case, interest in the concept of ‘world’ is more about the scene beyond Korea. But it is not contemporary jewelry as would be familiar to AJF readers. The ‘world’ framework is a humanist celebration of the diversity of traditions, rather than a critical discourse subject to its own internal history, as we like to see contemporary jewelry.

But it is certainly not a dull museological exercise. This particular primitivism engages with a quite expansive, poetic approach to jewelry. The intimate displays are complemented by sensuous descriptions of jewelry such as ‘footprints left behind by our hidden desires.’ This intimacy is sexualized: ‘The components of jewellery must view the human anatomy as their lover, freely running their fingers all over the human body from head to toe. Its flexibility and willingness to be physically manipulated is an open invitation to be adorned.’

As Korea begins to assert its own voice on the world stage, this international perspective is becoming more important. South Korea hosts two of the world’s most significant craft events, the Gyeonggi International Ceramic Biennale and the Cheongju International Craft Biennale. Rather than use these international events as a platform for Korean artists, they resolutely take on a global responsibility to reflect the diversity of art from different countries. While modest in size, the World Jewellery Museum reflects this role of Korea as a global cultural hub. It is worldly in a way that is characteristic of a once insular nation.

Because it is outside of the west, the World Jewellery Museum has the capacity to see western culture through this lens. Art nouveau and art deco sit alongside Ethiopian crosses and pre-Columbian artifacts. This ‘world’ offers a space for recombining jewellery cultures, from which something more global can emerge.