Untitled. Thomas Gentille. American Jeweler

February 27–June 5, 2016

Die Neue Sammlung—The Design Museum, Munich, Germany

Untitled. Without a name. This is how American jeweler Thomas Gentille’s retrospective, which coincides with this year’s Munich Jewellery Week, is introduced at Die Neue Sammlung. An expansive collection of his studio jewelry from the 1960s onwards is housed on the second floor of the Rotunda in Pinakothek der Moderne, an ethereal architecture filled with light that, owing to its circularity, has no start or finish: It simply revolves. This vertiginous space, coupled with the detachment of the jewelry pieces from specific dates, or any recognizable context—which, we are told, was the artist’s intention—expresses ambivalence toward art-historical categories, as well as the mechanisms of museum curatorship. Here, it seems, we are on Gentille’s terms. For a studio jeweler who has, arguably, received more recognition in the European context than in his native America, this feels right. Untitled. Unacknowledged? Maybe. Or rather: Unwilling to conform.

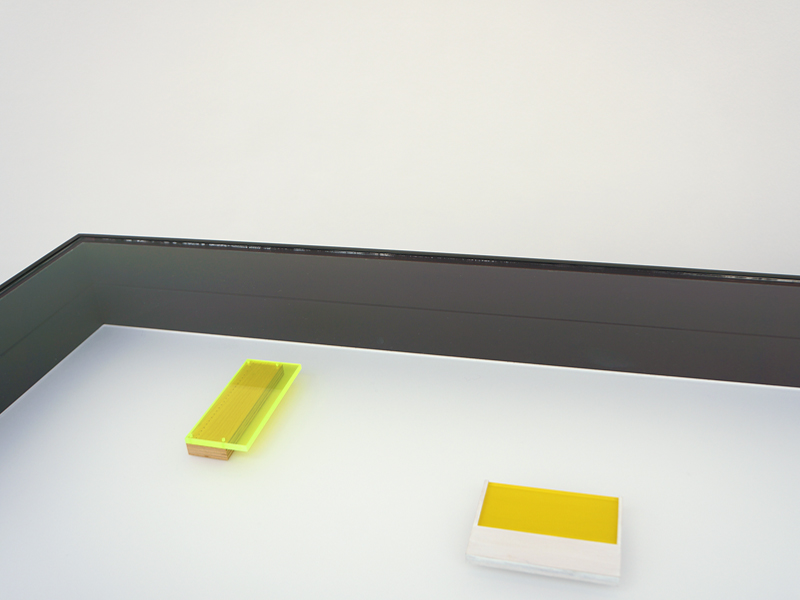

The exhibition is arranged in a relay of black vitrines around the Rotunda. On the walls, at eye level, hangs a sequence of color studies that resemble the color field painting of Abstract Expressionism—like miniature Rothkos. Two monitors positioned on the floor, equidistant from one other, flicker with a grainy continuum of dream-like images: bodies, textures, and architectures. I am reminded of Siegfried Kracauer’s preoccupation with the “fragments” of daily life and “fullness” of visual details recorded by the photograph.[1] Gentille is, in fact, passionate about film.[2] With these flickering vignettes of Munich and New York,[3] their shadowy buildings and metro stations, Gentille thickens the narrative of his “architectural” jewelry. They, too, become vignettes—souvenirs of the sidewalk, glass, bolt, and aluminum—well suited to the brooch form. Which brings me back to their lack of captions. There is something of the anonymity of modern life, here—of the ability to observe, to assimilate, and remain detached. The logic of these pieces is in their superfluity; dates would unnecessarily anchor them to time and place. Gentille wants us to focus instead on their textured surfaces and architectural geometry as fragments of a life spent looking and making.

Gentille’s approach to jewelry is born of his training in a multitude of craft techniques—from painting to ceramics and weaving. His work is nuanced by an awareness of Munsell color theory, of composition in painting, of the precision of woodcuts, and architectural form.[4] His sensitivity toward materials is evident in the correspondence between pieces. A series of brooches fashioned from aircraft plywood, paint, and pumice in muted reds and blacks that read like studies of Bauhaus architecture riffs on the quietude of a selection of maple wood and cherry wood brooches, devoid of color and placed alongside. In another vitrine, Gentille’s innovative method of eggshell inlay in pinks and blues (a technique that took him six years to master),[5] crackles alongside a clear acrylic pendant fastened with plastic pegs and wire. The softer edges of Modernism are evident in the carved-Formica Surell (synthetic resin) forms that resemble sculpted marble, while the synthetic nature of Pop Art can be read in the colored acrylic of Kinetic Armlet. Despite the lack of contextual information, Gentille’s body of work appears to explore the relationship between architecture and sculpture, where the horizontality of Frank Lloyd Wright’s “organic architecture” meets the minimalism of Donald Judd. There is a fizzle of visual dialogue among the works.

More importantly, however, Gentille’s materials feel commonplace, rather than exquisite: There is an ordinariness to them, which is his own protest against the overt preciousness of contemporary jewelry. This rendering of the modernist tenet of “truth to materials”—of the importance of respecting, in his own words, “the soul of the material”—is something that Gentille abides by.[6] It is visible in the soft lunar forms of black Surell and the unashamed fracture of eggshell surfaces. On the other hand, this reverence for materials has the tendency to render the jewelry uninteresting. In some instances there is little perceptible difference between an architect’s material samples, say, in plastic or sheet metal, and Gentille’s compositions. This difference, what Ann-Sophie Lehmann refers to as the “mimetic gap,”[7] needs to be widened for his pieces to be read on their own terms. For example, a vitrine of aluminum brooches is at once precise modernist geometry and a set of ordinary aluminum fastenings. Unwittingly, Gentille’s “truth to materials” quickly becomes derivative; these forms hover somewhere between artistic production and material swatch. It is an ambiguity that, at times, flattens the appeal of his work.

It is also disconcerting to remain so uninformed about the specific cultural context in which these works were made, especially in a retrospective. Throughout the course of his career, Gentille has witnessed the influence of Constructivism on American studio jewelry. He taught at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts and, later, Penland School of Crafts, where he directed the jewelry and metalsmithing program from 1974–1983, as well as publishing his own handbook, Step-by-Step Jewelry (1968). He was the first director of the 92nd Street Y’s Jewelry Center, New York, and the only American to be honored as a Klassiker der Modern in Munich’s International Handwerksmesse in 2006. This, in addition to winning the coveted Herbert Hofmann Prize in 2001, makes Munich his second home. However, all of this contextual richness is omitted, and instead, individual pieces are numbered, with the finer details annexed to a printed pamphlet. This disconnection between looking and knowing is certainly vexing at times. It was, in fact, Gentille’s aim to encourage a more intuitive response to his materials, forms, and techniques, and to create a space in which to think more carefully about his influences and precedents. It is a canny tactic, and one that is reflected in the resoluteness of the exhibition title. Untitled. Now it’s over to you.

Yet Gentille’s efforts to destabilize time are also counter-productive. The lack of contextual information forces you to search for it: to make clumsy connections where, with a simple caption, there would be no doubt. In an effort to read this “web of signs,”[8] of materials and techniques, the viewer finds that the work itself dematerializes. It is, after all, a bold move to distance the critic from his objects, which become things to be puzzled out, rather than engaged with. This purposeful deferral of context, of the ability to attribute this piece to that period, denies the audience the reassurance of situated artistic innovation. The decentering of the viewer’s body and mind is further augmented by the decision not to exhibit the work on mannequins, instead pinning it inside vitrines like mounted specimens, without life. These are not jewelry pieces per se, but objects of study: intellectual, not visceral. And herein lies the paradox of the exhibition: It is organized in such a way as to invite critique, although the lack of textual mediation obscures rather than illuminates. It forces these precise, minimal compositions to fend for themselves, and to deliver their quiet magic without discursive props, bar the immense seal of approval that the museum constitutes.

Depending on where you stand, the decision to deny Gentille’s generous retrospective some “proper” historical pegs is either counterproductive, or fairly progressive. To critics, like myself, the exhibition feels like stumbling, blindfolded, through a vast collection of things. Holding history in check suggests that art can happen regardless: without people keeping track. Others—and there were many “others” at the opening—will applaud the gutsiness of a maker who takes that chance. Whether his jewelry pieces were made yesterday or 30 years ago, Gentille’s work is (still) a few pegs above the cut. And with that, he makes a silent appeal to the audience to concentrate on the jewelry pieces themselves, and to find in them clues about what makes them great.

Perhaps it is because this is the first retrospective of an American studio jeweler that has been programmed as part of Schmuck that Gentille is so ambitious. Or perhaps this is his attempt to condition his critical reception after a lifetime of moderate critique. While it is, at times, difficult to submit to his inscrutable curatorial methods, Gentille is an enigma, and his approach lends this retrospective a certain gravitas. Untitled and Unknowable.

[1] Dagmar Barnouw, Critical Realism: History, Photography, and the Work of Siegfried Kracauer (Baltimore and London: John Hopkins University Press, 1994), 105 and 116.

[2] Oral history interview with Thomas Gentille, August 2–5, 2009, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[3] Untitled. Thomas Gentille. American Jeweler. 2016 (Munich: Die Neue Sammlung—The Design Museum, 2016). Exhibition pamphlet.

[4] Oral history interview with Thomas Gentille, August 2–5, 2009, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[5] Oral history interview with Thomas Gentille, August 2–5, 2009, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[6] Oral history interview with Thomas Gentille, August 2–5, 2009, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

[7] Ann-Sophie Lehmann, “Closing the Mimetic Gap, or the Galalithe Problem,” The Matter of Mimesis, CRASSH, University of Cambridge, December 17–18, 2015.

[8] Jean Baudrillard, ‘The Precession of Simulacra,” in Brian Wallis, ed., Art After Modernism: Rethinking Representation (New York: New Museum, 1984), 267.