The exhibition comes to MAD after being shown at the Oakland Museum of California, where it was curated by Julie M Muñiz in February 2012. The Oakland Museum houses the largest collection of De Patta’s jewelry in the world as well as archival material that includes account ledgers, sketchbooks and personal effects. Most of the objects were donated to the museum by Eugene Bielawski, De Patta’s husband. It is appropriate that the exhibition would take place on the West and East Coasts of the United States, since these were the two main centers for modernist jewelry after the war and into the 1960s. True fans should note that seeing one exhibition is not enough: while the two exhibitions include many of the same pieces, there are also some differences, not just in the display but also in the work on view.

A statement that today’s studio jewelers like to make is that they are artists, not craftsmen and use the medium of jewelry to express their ideas. In that sense, Margaret De Patta should be their role model. De Patta studied painting and sculpture, first at the California School of Fine Arts in San Francisco and later at the Art Students League in New York. She fashioned her first piece of jewelry in 1929 when unable to find just the right wedding band, she decided to make one. De Patta apprenticed at San Francisco’s Art Copper Shop but overall, not unlike many of her contemporaries, she was an autodidact, since jewelry programs were nonexistent. And like many great artists who spent their days wandering around museums learning from their predecessors, De Patta did too. The exhibition includes samples of her work from the 1930s, a pendant and a bracelet that, in its use of turquoise, were influenced by the ethnic jewelry she saw in museums. Two other pieces in particular, a ring and pin, from around 1937-1940, demonstrate her apparent interest in cubism. (As a painter, she was interested in European modernism). The designs, always in sterling silver, are strong and sophisticated resembling the work of Jean Despres, the great art deco jeweler. From this selection of early works we can already see the traits that would later define De Patta as a leading figure in American studio jewelry: primarily interested in the form, she eschewed precious materials, instead crafting her pieces out of sterling silver and accenting them with turquoise or malachite.

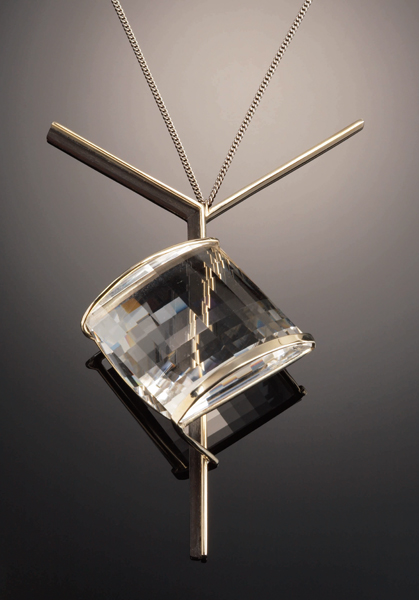

In actuality, De Patta employed several materials that were unorthodox for jewelry, including the aforementioned rutilated quartz (also known as a Venus hair stone for the very fine needle-like or hair-like inclusions that are found in it.) She used several different variations of this stone, some with black inclusions and others with a burnt red. De Patta did not want the mounting to interfere with the design of the piece, the natural beauty of the stone or block the light that would pass though it. Several rings have a shank that is slightly twisted and open in the back. So while the mounting isn’t supposed to detract from the piece, it is also very sculptural. Every design detail is clearly thought through.

Moholy-Nagy, a painter and photographer, was involved with the Bauhaus in Germany but relocated to Chicago in 1937 finding it difficult to remain in Europe with Adolf Hitler’s rise to power. The New Bauhaus, a school based on the principles of the original Bauhaus was only in existence from October 1937- June 1938. At that initial 1939 lecture, Moholy-Nagy talked about the Bauhaus and the School of Design in Chicago, which he recently opened after the New Bauhaus closed. This lecture resonated with De Patta since she visited the school in Chicago. She proceeded to enroll in a summer course that Moholy-Nagy was teaching at Mills College in Oakland following a traveling exhibition, Bauhaus: How it Worked, in Mills College Art Gallery in 1939. From 1940-1941, De Patta studied with Moholy-Nagy. Already a serious jeweler, she proved to be a competent protégé who through her jewelry adhered to his principles of constructivism.

Artist Rupert Deese’s presentation of the jewelry in the main gallery is ethereal; De Patta’s key pieces are exhibited in their own glass domes, floating in space, just the way De Patta intended them to be seen. The unique, one-off pieces of De Patta’s jewelry are placed in individual cases, wall text off to the side, the light hitting each piece at just the right angle so that we see the nuances that De Patta wanted us to. The multiple pieces from De Patta’s Designs Contemporary line are all grouped together in large display cases, although some are exhibited with original drawings or photographs. Most often jewelry in exhibitions is displayed all together in long display cases that line the walls like in a boutique, but with paintings there always needs to be a certain amount of space in between, providing the work with sufficient room so that we can appreciate it properly. With this exhibition, each piece of jewelry is given enough space so that it is raised to the same level of ‘importance’ as a painting or a sculpture. For an artist like De Patta, who said that she made ‘wearable sculpture,’ this is exactly what she deserves.

For the exhibition, Ilse-Neuman brought in Moholy-Nagy’s Light-Space Modulator film (1935) as well as a Plexiglas sculpture, which helps us see the constructivist’s principles of translucency and light in action. But what does this all mean in practical terms? According to Ilse-Neuman, again writing in the catalog, ‘Moholy-Nagy’s most direct contribution to de Patta’s jewelry was probably in the use gemstones of as conveyors of light and motion.’ Glenn Adamson’s essay, ‘Balancing Act: Margaret De Patta and Constructivism’ in the exhibition catalog delves even deeper and is a superb overview not just of the history of constructivism and its key players but an explanation of how De Patta was able to take the complex principles of the constructivist and express them through her jewelry, which as Adamson writes, could not have been easy for her. Moholy-Nagy often told De Patta to ‘catch your stones in air, make them float in space.’ According to Adamson, ‘This was based on the Constructivist ideology of autonomous abstraction, by which a painting or object was created as a self-enclosed world of form. Her ‘opticut’ jewels and chunks of faceted quartz, in which stones were cut so as to produce an elusive, refractory effect, were a particularly ingenious means of achieving an impression of compositional autonomy.’

De Patta was not just influenced by the formal qualities of Moholy-Nagy’s work but also by the socialist principles that he and the Bauhaus promoted: good design should be available to all. In 1946, De Patta and her husband Eugene Bielawski founded Designs Contemporary, whose logo was ‘jewelry for an ever increasing minority.’ The major difference between the Design Contemporary pieces and the unique pieces, was that the former were made of sterling silver, never white gold as sometimes was the case with the one-off pieces and stones were rarely used, or if they were, it was never an opticut but a pearl or a crystal cabochon. The line started with six pieces, increasing a bit each year and by 1955, De Patta had 106 sketches for the series, although no more than the first 61 were ever produced. The jewelry varied in price from $13 to $50. Most importantly, all of the pieces were hand cast by Bielawski.

In the catalogue essay ‘Jewelry for a Never Increasing Minority: Margaret De Patta in the Marketplace,’ Julie M Muñiz, co-curator at the Oakland Museum, philosophizes why this endeavor was a financial failure. To our contemporary rationale it is unthinkable that De Patta’s work, which at the time cost no more than $30, did not find buyers. However, put in perspective and adjusted for inflation, $300 may not have been a sum that middle-class housewives could easily part with. Muñiz points out in those times an Eames dining table cost $34 and a 14-karat gold ring with semi-precious stones was half the price at Sears, Roebuck and Company. According to Muñiz, De Patta did not understand her market well enough. While De Patta and Bielawski were able to get the jewelry into design shops, it was met with great price resistance. The Designs Contemporary pieces are all extremely thought-out, both in the design and execution. The designs are all original and rather sophisticated, not cheap imitations of the good stuff. The only complaint is that they are a bit heavy, missing some of the lightness and airiness that characterizes De Patta’s work. However consumers did not find the jewelry interesting enough or well made enough to garner the high price.

The entire exhibition would delight any collector of De Patta’s work, but especially this section only. This is because it is still possible to find examples of Design Contemporary pieces on the market and the section includes a myriad photos, sketches, pages from brochures and rubber molds that can help identify certain pieces.

Throughout this exhibition there is enough wall text to give the viewer an understanding about De Patta’s techniques, her connection to the Bauhaus and her fascination with the constructivist movement, but anyone who wants to really know more should turn to the superb exhibition catalog which is more than a worthy companion to this exhibition. The three informative essays, written by Ilse-Neuman and Muñiz, the co-curators, as well by Adamson, the craft historian, are joined by beautiful illustrations of all of the jewelry and ephemera from the exhibition, including jewelry sketches, brochures and photographs of De Patta. Especially valuable is a list of all the production pieces, accompanied by photos that De Patta took of them, with original retail values. The book also includes a timeline of De Patta’s career, which is also featured in a separate display case in the exhibition but proves to be more effective here because you have time to read it and do not feel compelled to move on to the jewelry.

Overall this exhibition is a joy. It is beautiful jewelry, presented in a beautiful way. Most importantly De Patta would be proud of the exhibition. Proud that people really understand her work and that proud that, almost fifty years after her death, there is an appreciation for what she achieved.