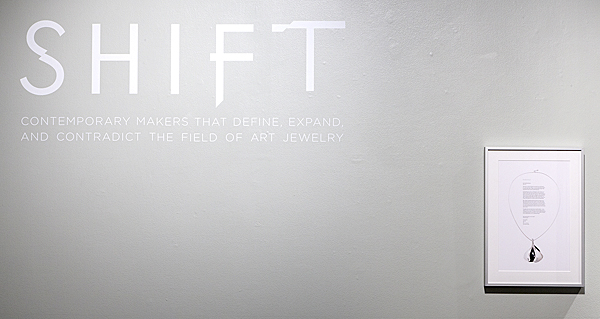

Shift

October 18–November 21, 2013

Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana, USA

Within the American Midwest, it is a rare opportunity to come across exhibitions of contemporary jewelry or galleries with an art-jewelry focus. It is neither Germany nor the Netherlands, and with the yearly exception of SOFA Chicago, a handful of craft center/gallery combined spaces, and perhaps SNAG’s annual conference making its rounds to these parts, the Midwest is longing for more. That being said, it is home to many students and faculty at some of the best institutions for jewelry and metalsmithing: University of Wisconsin-Madison; Cranbrook Academy of Art; my alma mater University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, and Indiana University Bloomington, to name a few. It is the latter that whetted the Midwest’s appetite for contemporary jewelry this past fall with a weekend full of events. The Zoom Symposium was held at Indiana University’s Henry Radford Hope School of Fine Arts on October 18 and 19, 2013. It consisted of a handful of workshops, a lecture series, and nine separate exhibitions, all seeking to “examine the future of craft.”

The Organization

Shift: Contemporary Makers that Define, Expand, and Contradict the Field of Art Jewelry, an exhibition of more than 70 works by 25 national and international artists, was held at the Grunwald Gallery of Art in conjunction with the Zoom Symposium. This exhibition was a collaborative effort organized by the students and faculty, Professors Randy Long and Nicole Jacquard, in the metalsmithing and jewelry design program at Indiana University Bloomington and funded by the 2012 AJF jewelry exhibition award.

A catalogue accompanies Shift, and a copy was given to all registered participants of the symposium. The catalogue includes a full spread for each artist, with a statement and an image of his or her work, as well as two essays that discuss the current shift in the field today: “It’s not this or that. It’s and.” written by Anne Fiala, a recent Indiana University MFA graduate student; and “What would Alma Eikerman say?” written by Australia-based jeweler and scholar Robert Baines. In her essay, Anne Fiala states that the Shift exhibition “seeks to highlight some of the contemporary makers, who through their choice of materials, processes, concepts, and philosophies, are defining, expanding, and contradicting the field of art jewelry today.”

The curatorial process for Shift was collaborative from start to finish. The students and faculty of Indiana University held many brainstorming sessions to determine the nature of the show, its concept and title, and finally, to curate a select group of artists that fit within the idea of defining, contradicting, or expanding the field. The 25 artists represent a variety of backgrounds and experience in the field. From studio jewelers to educators and craft activists, they strike a balance between gender and age and show breadth in technique, process, and material.

The Curatorial Bid

The selection process for the work varied for each artist. Some were asked to send specific work while others sent work they felt fit with the scope of the show. In general, the organizers tried to keep the show as current as possible, and few artists had work that I would classify as “older.”

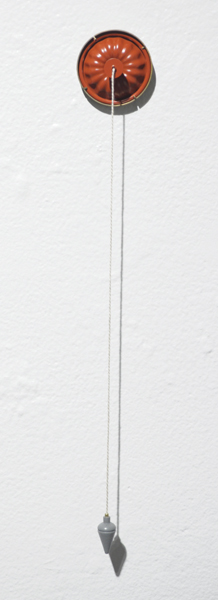

The pieces ranged from jewelry of a traditional, more wearable scale to larger works that function more like sculpture, both on and off the body. I was glad to see jewelry of a larger scale, as well as objects and installations, as this is an accurate representation of the contemporary art jewelry and craft field today. Artists are not only using jewelry as a medium to express their ideas, but they are also expanding their practices to include community engagement, activism, and collaboration, and using the context of jewelry to question ideas of value, preciousness, and interaction with the body. They are doing this hand in hand with, or entirely separate from, traditional craft practice. Artists are employing new technologies, such as CAD/CAM, water-jet cutting, laser etching, and even Arduino programmed electronic objects. They are contradicting historical processes with innovative approaches, and of course, utilizing a multitude of materials to do so.

The term shift implies movement, and unlike the ideas of change or revolution, it still has ties to what came before. It isn’t about a radical difference or a wholly different entity but about repositioning, reworking, modifying, or altering. Shift has roots that are recognizable. They might be celebrated, questioned, countered, or reflected upon, but ultimately they are key to understanding the present state of the evolution.

In my mind, a better suited title and more accurate description of the current state of contemporary jewelry would be Shifting, an active indication that it is in flux, continual, and a part of the present moment. Rather than suggesting that the shift has already occurred, it suggests that it is occurring.

The subtitle of the exhibition—Makers That Define, Expand, and Contradict the Field—gives the viewer an idea of how the curators feel the shift has occurred. It is through this lens that I viewed the exhibition and examined what sort of expansions and contradictions defined the said Shift.

The Exhibition

Upon entering the exhibition, I was greeted by a title wall positioned at an angle and painted a soft green color that matches the catalogue’s color and design. The angle of this wall invited viewers to enter and move through the space. Works were displayed on custom designed and built tables and wall mounts. The tables filled the center of the space, were positioned at the same angle as the title wall, and sat at varying heights. Nicole Jacquard, who designed the display for the show, hoped these simple white tabletops with bare wooden legs would allude to an examination table without being overly scientific, and I think this was achieved. The height of each table, the specific spotlighting, and the lack of vitrines allowed viewers to get up close and personal with the works and to truly examine them in detail. In addition, the wall mounts lined the gallery walls at shifting heights, and the work was attached directly to the boards or positioned on mounted shelving.

[video: http://vimeo.com/35931179]

Work and Mediation

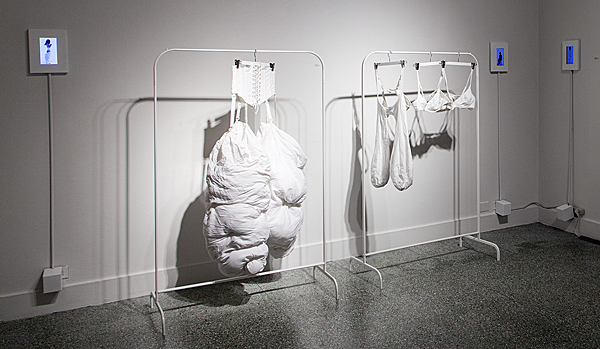

Lauren Kalman’s work was displayed in a small room-like space at the back of gallery and incorporated interactive wearable objects, sculptural garments, and corresponding videos. This succeeded in providing the viewer with an intimate understanding of her work’s relationship to the body, which addresses the private or hidden aspects of the human body. Objects were displayed as artifact of use and performance props, as evidenced in video and wall texts. The physical remains leave a visceral and material connection to the work, bringing it closer to oneself. The garments are made from a white fabric that seemingly grew from or on the body, referencing the disease elephantiasis. The electronic wearables digitally simulate viruses such as syphilis. Kalman’s reference to disease, presented through objects typically associated with beauty, status, or wealth, presents both a contradiction and an expansion of the ideas related to jewelry. In this case, the objects “shift” between the realms of the grotesque and the beautiful or desirable.

Raising Awareness, a collaboration between Gabriel Craig and David Huang, consisted of a display of several traditionally raised copper vessels and a supplementary video. In this video, viewers are shown that the process of making the vessels came out of a craft-based performance that engaged and informed the public about the traditional technique of forming flat sheet metal with hammers and stakes into volumetric form. Through physical demonstration and public interaction, this craft activism and dissemination of knowledge gives the audience (both those at the actual event and those in the gallery space) an intimate understanding of how objects are made. In this case, the video is critical to understanding how the work is expanding the field. This physical expansion of the metalsmith’s studio into the public sphere challenges our perceptions of craft practice, something the objects alone don’t do.

Conversations

An aspect of contemporary jewelry practice that was prevalent in almost all the works in Shift was the use of traditional and new materials. I hesitate to discuss the use of nontraditional or “new” material because I think we know that contemporary jewelers use a variety of materials within their practice. Perhaps the more relevant conversation isn’t about what materials artists are using, but how they are using them and to what end?

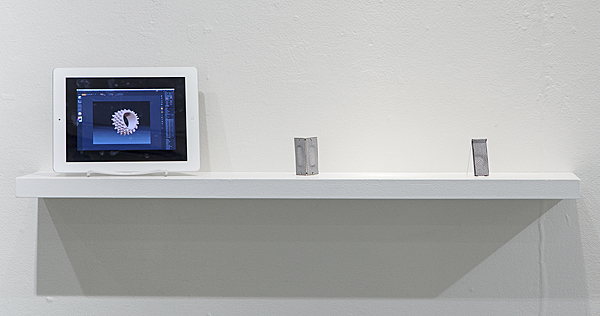

Artists are also utilizing new technologies to manipulate materials for both traditional and more experimental uses. Creating 3D-rendered objects in plastics through CAD/CAM software that can then be cast, laser etching traditionally enameled forms for a precise surface treatment, and programming objects to respond to one another with LEDs and Arduino software, are a few of the processes represented at Shift.

It is interesting to note the way some artists are using technology not as a means to make the entire piece but as just another tool at their bench. Limitations in technology and the distance from the individual artist’s hand and the physical act of making tends to produce work that lacks identity and holds the aesthetic of the machine used to produce it. The more familiar artists become with various technologies, the more they can utilize or manipulate them to bring authorship and individuality to the work.

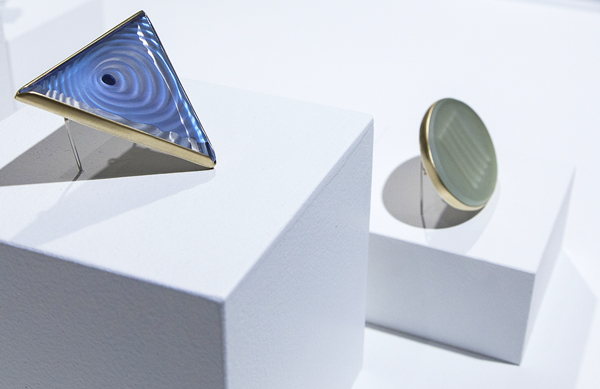

Donald Friedlich’s use of technology in his glass jewelry encompasses exactly this kind of hybrid process. He is modifying not only the visual language of iconic symbols such as Greek columns, but also the methods by which they were produced. For instance, his blue triangle brooch started with a CNC-carved graphite mold, and then hot glass was pressed into the graphite form, utilizing technology as a tool in his craft and creating a work that is uniquely his.

Conclusion

Shift succeeded in bringing together a diverse set of makers whose amalgamation of experience, technique, and the fresh perspectives make up an important facet of this field. However, as I reflect on the exhibition, it is hard to gauge where the shift itself comes from. Or where it is going for that matter. With such a wide range of makers represented, it seems that Shift was more of a snapshot of the current state of contemporary jewelry through the lens of the students and faculty at Indiana University; a select and partial showcase of what is happening, for the most part, now. I’m not sure that the artists chosen for the exhibition consciously attempted to shift the field, and perhaps it is too broad an idea or too difficult a proposition to make sense of a particular shift in a field that is always changing.

Artists have practices that are ongoing and evolving, and due to this I think that the title Shifting would suit this show more accurately. It is because of these artists, and many others, that the field is continuously redefining itself. The active notion of shifting encompasses the ways the redefinition is, and likely will continue to be, taking place through expanding and contradicting our perceptions of contemporary art jewelry.