1984

May 20–July 27, 2024

Galeria Zé dos Bois, Lisbon, Portugal

This summer, the second Lisbon International Biennial of Contemporary Jewellery celebrated 50 years of democracy in Portugal, focusing on freedom, power, and democracy. The official program presented Teresa Milheiro’s solo show, 1984, at the Zé dos Bois (ZDB) gallery. This exhibition served as a rebellion, reflecting on how individuals are defiant of societal pressures.

Milheiro, like many Portuguese jewelry artists, attended Ar.co and taught there. She’s the co-founder of ZDB gallery and ran her own gallery, Articula. Her works have a strong political dimension and are often society-critical. She has been an anarchist (she is uncertain whether she still is) and this rebellion and freedom are evident in her works. The exhibition 1984 presented new works together with works from her 40-year career, all politically charged.

I was struck by the emotions 1984 evoked. Four months later, what I remember most is the feeling I got: uneasy and shaky. I remember a mix of excitement and disturbance. I was impressed with the show’s scale and shocked by some of the materials. The dark and mysterious gallery space, with its arched ceiling, was impressive. The huge wooden doors were open to the streets, letting in the only light in the front room. The exhibition spread across four ground-floor gallery rooms, the first three taking visitors deeper into the building. The dimly lit, cave-like gallery cast a shadowy glow over Milheiro’s somber works telling stories of oppression.

Milheiro’s work explores the tension between the individual and the communal self. While expressing individuality is important, group pressure can make people conform. Where is the line between the societal creature and the individual one? What if someone resists? Is there punishment? Milheiro plays these tensions out on the body.

In capitalism, the body is a canvas for individual expression. It is also a place where societal norms and accepted ways of being are presented. Milheiro’s necklace Desperately looking for a wrinkle highlights the obsession with youth and the vulnerability of aging. Society pressures us to look young and perfect. Abandoning that standard is a bold statement. I recall the scorn I faced for wearing dirty jeans on the streets of Tallinn. I couldn’t endure it for more than a day. I was shamed into dressing “properly.”

The body doesn’t like being judged. Milheiro’s creations show the body’s vulnerability while simultaneously offering it protection and placing it under threat. Some of her works might hurt.

Anti-bite fingerstalls, from 1989, stop anxious individuals from biting their nails. The sharp claws protect the nails from the teeth. Milheiro also plays with the symbolism of body parts. The cut-out tongue symbolizes censorship. The tied eyeballs in The eyes are useless when the mind is blind symbolize not wanting to think nor see. The lined noses symbolize sickness and beauty standards. “Art doesn’t have to be beautiful but should provoke thought,” states Milheiro.

She thinks of political matters in her life and work. Her work One Way System critiques the lack of acceptance for nuances. It shows a missing place for those undefined by regulatory standards. People who don’t fit into categories cause confusion and are misplaced. “You either have to be this or that, left or right, like there is no in between,” says Milheiro. The work is made of two mirrors with a needle pointing to the forehead. The two mirrors act as two eye patches to look in a single direction: at the needle. The work warns the individual not to err from the one and only way. “The official narrative is that there is only one way,” says Milheiro. To find another way, you need courage.

![Teresa Milheiro, One way system I, 2021, leash, glass syringe, steel, brass, chrome-plated brass and mirrored acrylic, 18 ½ x 7 ½ inches (closed) to 13 ⅛ x 9 ⅝ inches (open) (470 x 190 [closed] to 335 x 245 mm [open]), photo: Eduardo Sousa Ribeiro, 2024](https://artjewelryforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Teresa-Milheiro-One-way-system-I-2021-Photo-by-Eduardo-Sousa-Ribeiro-800x600-1.jpg)

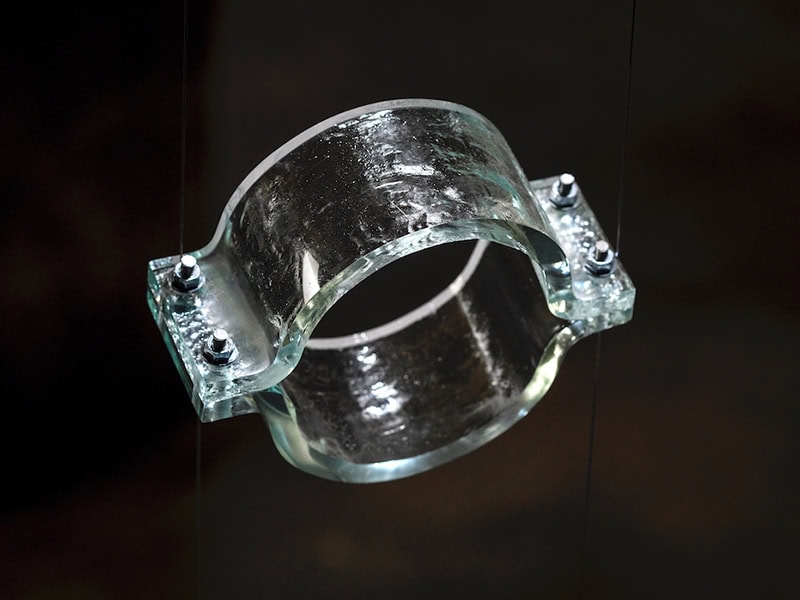

The Pressure series, made in 2023, shows the power of breaking free from societal constraints. The collars and bracelets explore individual strength. Visually, they resemble the collars and cuffs that slaves were forced to wear. “They are made of glass, giving the wearer the power to break them,” Milheiro says. The neckpiece breaks when attached too tightly. It shows how much pressure things/beings can take before they break or break free. Working with glass taught Milheiro self-acceptance.

“Glass is a fragile material that needs to be handled with care; if not, it breaks and is lost,” she says. “I’m starting to accept my fragility; for years I didn’t. I had to be strong and unbreakable. I wanted to pretend I was indestructible,” she continues. Working with glass has taught her about the caring nature of relationships. “Glass has to be taken care of, just like the relations between people and ourselves, otherwise they can break,” Milheiro says.

She started exploring fragility in 2019 when she had a show with Leonor Hipolito called The Power of Fragility. There she looked at fragility through the lens of the history of mental illness. She exhibited lobotomy and gynecology tools.

Egas Moniz, the inventor of the lobotomy, was from Portugal. Milheiro’s research concluded that 85% of lobotomy patients were women. After the procedure, they lived in an apathetic zombie-like state. The female body has been a victim of monstrous power for centuries. This is a source of nightmares. Yet Milheiro is not afraid to roam there and show her discoveries.

The exhibition’s climax was the dimly lit room at the end, featuring the same lobotomy tools. It was my favorite part because it felt like entering a dark bunker. Milheiro intended it as one, where body experiments occurred. Historical material from doctors’ cabinets adorned the walls. The glass bracelets from the Pressure series hung brightly in the dark, confined space. A suitcase filled with unsettling equipment freaked me out but I kept looking. A neurologist’s grandson provided Milheiro with zinc sheets, brains engraved on them. They were used for medical books. She used them for wall installations.

The light focused only on the works. The arched ceilings evoked an underground prison. That room reminded me of a former secret KGB facility in Tartu, near my great-grandmother’s home, in an ordinary-looking apartment building’s basement. 1984 was a sobering reminder that those kinds of “correctional” centers haven’t vanished from this earth.

Milheiro’s commentary on the human tendency to comply and surrender to societal conformity resonated with me. Self-knowledge is a difficult path. It often involves shaming others for not fitting in. People will go to great lengths to be loved and accepted. Who dares to walk their own way, when even dirty jeans can cause scorn? To stand alone and face the pressure of not being liked takes real courage. “Courage is much needed in today’s world and in the art world,” says Milheiro.

1984 demonstrated Milheiro’s courage and artistic vigor. She seemed to say she’s reached individual freedom and isn’t complying to society’s version of normality. Yet her voice contributes to society. She is speaking up and speaking her mind. I would like to see how she would express the state of freedom that lies beyond breaking free from social constraints. Until now she has been focusing on realism, but what would her hope look like?

Milheiro is a political artist, and her show fitted this year’s Lisbon jewelry biennial’s theme of political jewelry. Her 1984 was a rebellious shout, a provocation to think. It was a call for misfits to keep misfitting.

This exhibition was accompanied by a brochure. Visit the website for Galeria Zé dos Bois here.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org