KLIMT02 Gallery, Barcelona, Spain

October 7–November 7, 2015

In 1956, Glenn Gould totally broke the classical music panorama with an astonishing, energetic, passionate execution of Bach’s Goldberg Variations: A new language and a new approach to Bach were definitively on the stage.[1] From that moment, the sound changed, and that release, which launched Gould’s career internationally, is credited for integrating the Variations in the “contemporary” repertoire. Twenty-five years later, in 1981 (one year before his death), Gould recorded another version of the same œuvre, and again a new sound came out. Considered as the testament of the pianist, the 1981 edition is more intimate than the previous one: An autumnal feeling pervades all the Variations and, if passion is still there, it’s more temperate and there’s— I think —a delicate thread that links the entire execution in a unique, subtle canto. An ending and starting point at the same time.

It might be considered unconventional to start this review for the exhibition To Recover—organized by KLIMT02 gallery in Barcelona—by talking about a specific episode in the history of classical music. To me, however, this historical anecdote is connected to the proposal that the two KLIMT02 gallery directors—Leo Caballero and Amador Bertomeu—extended to 13 of their artists: Interested in discussing the notion of time, Caballero and Bartomeu asked the artists to reconsider, re-create and reinterpret one of their works made years before.

“We always consider an artist’s career as a progression, something in continuous change, development,” Bertomeu told me when we talked together about the concept of the exhibition. “Time passes, it is made, interpreted, felt, and suffered, it escapes, drifts away, becomes trapped or stretched, sometimes it is intelligently ignored, and, why not, it is exercised. Reinterpreting a work, a fiction, or precis is a way of addressing time, a way of exploring a landscape in order to try and understand it. And we thought this exercise would provide an interesting opportunity to discuss time.”[2]

It took almost one year to conceive and organize the entire exhibition. All the artists involved—Karl Fritsch, Gésine Hackenberg, Simon Cottrell, Karin Johansson, Jiro Kamata, Sari Liimatta, Stefano Marchetti, Ted Noten, Noon Passama, Annelies Planteijdt, Tore Svensson, Lisa Walker, Manon van Kouswijk—chose a specific piece and reworked it for the exhibition, providing an individual answer to the initial question posed by the gallerists about “revisiting” their own pieces.

Displayed in the cozy interiors of the gallery, the new and recomposed pieces were arranged on the surfaces of the table and of the wall-shelves. Every piece was accompanied by a thoughtful caption that explained—in more or less explicit terms—the relationship between the old piece and the new one, with the statement of the artist.

Displayed in the cozy interiors of the gallery, the new and recomposed pieces were arranged on the surfaces of the table and of the wall-shelves. Every piece was accompanied by a thoughtful caption that explained—in more or less explicit terms—the relationship between the old piece and the new one, with the statement of the artist.

This triangular setup successfully encouraged inquisitive contemplation, and contributed in no small part to putting time at the core of visitors’ experience of the show: the time it took to observe the two pieces, to read the statement, and to understand what was going on.

For this review, I’ll consider only three of the 13 artists involved in the exhibition: Some of them struck my eyes and my sensibility, others made me reflect about the status of an artist and his or her career. The gallery directors asked, “Are there any changes in these artists’ works? Should there be? Is time involved? Without a shadow of a doubt, the answer is yes. But that barely scrapes the surface of what we want to know. We’re more likely to find out what we want to know if the work enables us to answer questions such as: What kind of time is involved? Is there any usefulness? Is there any spirituality? Are there any aesthetics? Is there any abstraction? Is there any progress?”[3] I’ve tried to answer all these queries, but the great question in my mind is: How does it feel for an artist when he/she is asked to stop for a while and rethink the work done years before (it might be just one or the entire career)? This—in my opinion—implies humility, objectivity, honesty … and, of course, time.

A close study of the pieces highlighted the difference of commitment—and of strategy—of each exhibitor. Some artists made a clear comeback to the true essence of the piece; others chose to “amplify” the older piece, both by material and size; several, in the end, seemed not to have had the time to revisit the piece and just made small adjustments (both related to the concept and the piece). A few, finally, offered interesting, intriguing questions of their own.

I had a soft spot for the works of Karin Johansson, Noon Passama, and Tore Svensson, probably because I looked at those pieces not only with the eyes of a simple visitor, but with those of the avid collector.

Karin Johansson reinterpreted a necklace from 2003 by subtracting the oxidized silver elements that formed the bulk of the structure and, in keeping with her ongoing interest in lightness, she focused instead on the delicate rings that joined all the elements together and gave them a sense of rhythm. Thus, a series of gold rings was lying on the surface of the table pulsating with unbearable lightness. In her statement, Johansson pointed out effectively that, “The starting point of my new pieces is a necklace in oxidized silver made in 2003. I always enjoyed the way it moves, the sound it makes and how the parts are connected with a double ring. To point out, and make the playfulness and rhythm in the necklace more visible I lifted out and set the rings free. Two + two + two+ … became 12 golden rings.”[4]

Noon Passama’s Formal Research necklace has a precise starting point in one of the most common types of jewelry: the chain.[5] In her reinterpretation of the chain form last year, the links are not perfectly circular but almost “curl” with thin and rounded parts. For this project, they were reconsidered in isolation from one another, as singular rings, following specific operations, such as dividing/sequencing/sizing.[6] She chose to give voice to each element, setting it free from the whole work, but also stayed focused on the relation between the single elements connected with the others. The result, truly like a musical variation, creates a visual echo chamber: forms that seem mutated from one another, and are best appreciated as a group.

Both Johansson and Passama revisited their works, going back to essence and forms, giving more time to the initial piece—to prolong its existence, one (cut-up) segment at a time. But time, liquid in its true essence, could be both absolute and relative, and if Johansson chose a piece made 12 years before, Passama opted for a necklace made in the same year. Time flows at different speeds for each of us.

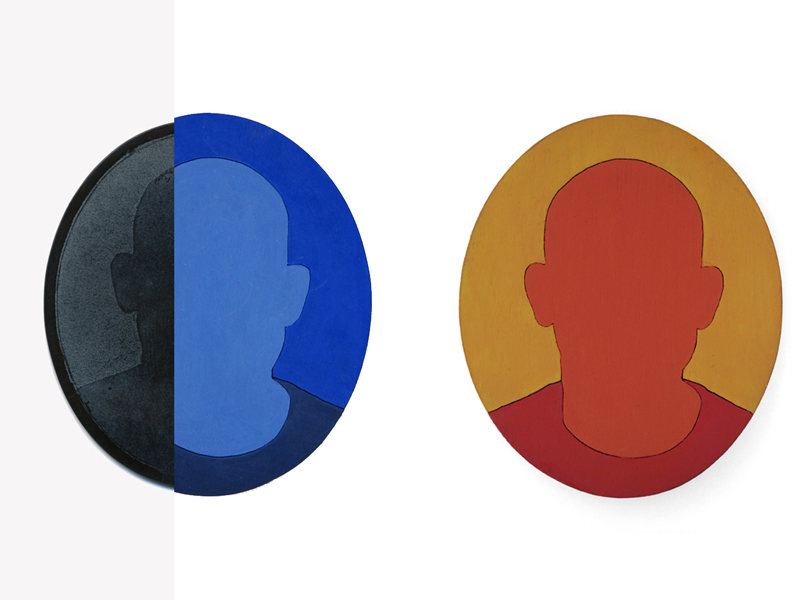

And then Tore Svensson: His portrait brooches, delicately etched silhouettes on steel, are contemporary reinterpretations of ancient and Renaissance engraved cameos. He chose to revisit his piece by changing material—using a wood veneer instead of the usual steel—enlarging the size of his brooch (a self-portrait) and painting it with different colors. Svensson remarked how “the sense of time is emphasized by the bigger size, which is possible by the lightness of the material, and is completely different from the original steel one. While the surface of the steel portrait and other previous work was the key technology for building the image, the colour for some years has been a part of my jewellery.”[7] In this sense and in my opinion, both the introduction of colors and probably the larger size of the brooch indicate the passage of time, and attest to personal artistic growth.

Aria da capo.[8]

Time encouraged the 13 artists to introduce a real change to their work, asking them to show clearly what they felt; it forced the curators to a very strict selection, and it obliged me (the viewer) to look carefully, rather than speed-date my way through the exhibition as one normally does.

For artists and viewers, time implied a stop in which both parties had to reconsider all the works done since that moment, showing not only a real and tangible “before and after,” but also the flowing of a creative time that is extremely personal and peculiar to each of us.

The curators’ aim has been generously fulfilled: Their commitment suggested the need of a reflection, of criticism and knowledge. Nonetheless, this experiment was—as far as I know—the first of its kind. In retrospect, it is surprising that no one has tried it before. It puts reinterpretation—a notion that is central to jewelry and to classical music, but often sidelined in contemporary art—at the center of one’s experience of the show. It also put a different spin on the question of time and craft: What is showcased here are not only long hours of accumulated skills but also the simple ability to backtrack, revisit, leap forward, or stall. This time—the time one needs “to recover”—is the one that implies respect and humility, otherwise, there’s no progression or development, in a word, no culture.

[1] Glenn Gould recorded the Variations in 1955; they were released by Columbia the year after.

For Glenn Gould see Kevin Bazzana, Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould (Toronto: McClelland & Stewart, 2004).

See also The Glenn Gould Archive: http://www.collectionscanada.gc.ca/glenngould/028010-1000-e.html?PHPSESSID=t3htl11hjch0iipaut2tmk0sl1.

The Glenn Gould foundation: http://www.glenngould.ca/.

[2] Amador Bertomeu and Leo Caballero, as quoted on their website, http://klimt02.net/events/exhibitions/recover-klimt02-gallery.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Karin Johansson, as quoted in her statement for the exhibition in http://klimt02.net/events/exhibitions/recover-klimt02-gallery.

[5] Noon Passama, as quoted in her statement for the exhibition in http://klimt02.net/events/exhibitions/recover-klimt02-gallery.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Tore Svensson, as quoted in his statement for the exhibition in http://klimt02.net/events/exhibitions/recover-klimt02-gallery.