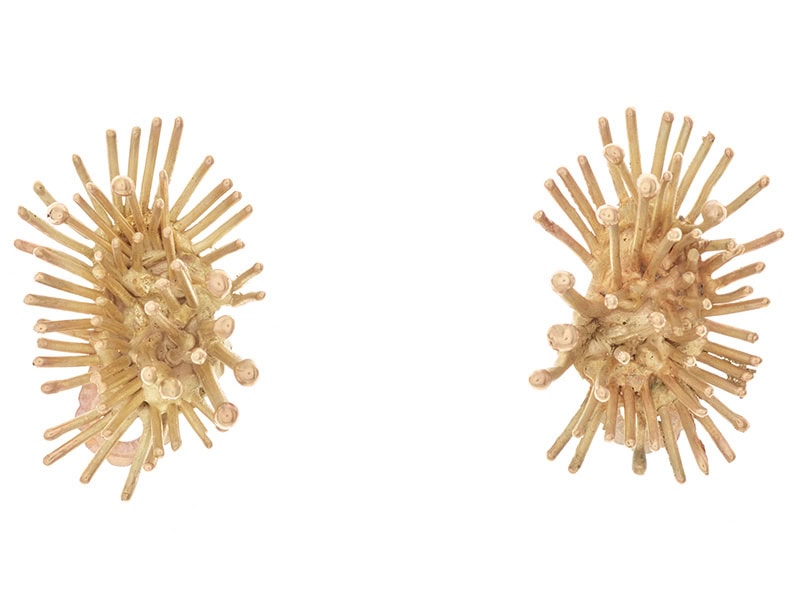

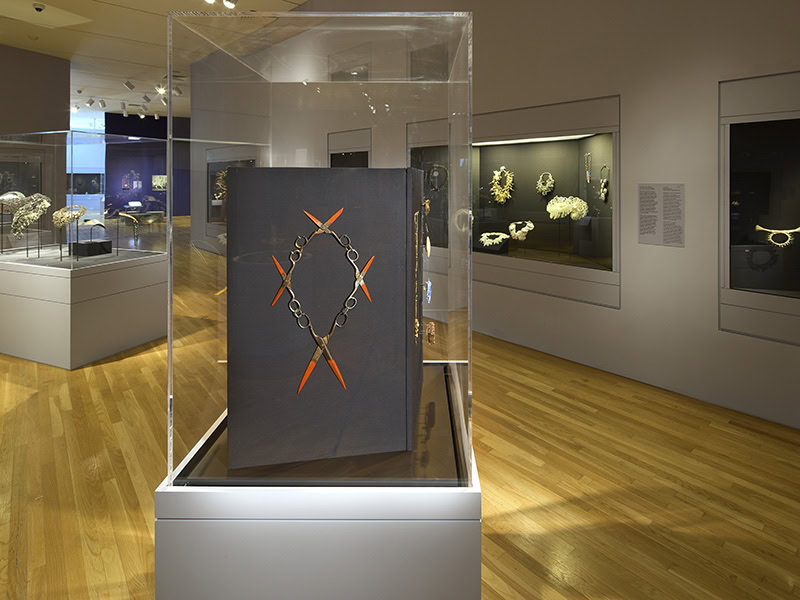

Constellations: Contemporary Jewelry at the Dallas Museum of Art

November 9, 2025–May 3, 2026

Dallas Museum of Art, Dallas, TX, US

What is a review, and what exactly does it judge? Is it the selection of works, the logic that holds them together, or the values a field assigns to itself at a given moment? While writing about Constellations, these questions quickly moved to the foreground for us, and led to a more fundamental inquiry: What is the value of an exhibition, and what makes for a good one?

Closely tied to this question is another, less visible, one: Where does the narrative lie when an exhibition presents a collection formed through years of personal decisions and preferences? Rather than unfolding through a declared curatorial script, the narrative emerges through the silent logic of selection—through what is placed side by side, and through what remains absent.

Is the value of an exhibition defined by the quality of the collected works—by presenting what is considered the “best” of each artist? Or is an exhibition always shaped by the field itself: by its histories, hierarchies, and points of view? Every exhibition is a form of arrangement, and therefore a form of judgment. The question then becomes: What is being evaluated in Constellations? How does contemporary jewelry appear within this framework? And who ultimately determines these terms?

Rather than offering a single, linear narrative, Constellations builds meaning through relationships. Individual works remain distinct, yet together they trace generations of jewelry makers—revealing how ideas circulate, shift, and take new form over time. The exhibition does not seek resolution; it holds difference, allowing multiple voices to exist side by side, at times aligned, at times in friction.

To better understand this context, it is useful to recall how contemporary jewelry emerged in many places as a material revolution. Through materials, jewelry spoke politically—often directly—about international relations, local economies, cultures, and landscapes. In works from the 1960s, 70s, and 80s, material culture can be read almost as a map: gold, steel, plastic, found objects, or nonprecious materials carried the imprint of specific countries, regions, and political realities. Materials were never neutral; they were loaded with meaning, availability, and resistance.

Collections formed before the internet often carried a strong sense of national or regional identity. The origins of the makers were legible in the work itself, and the collection became, in that sense, a portrait of place. One could trace not only aesthetic tendencies, but also cultural and political positions embedded in material choices.

In more recent decades, however, these boundaries have become increasingly blurred. The identity of a country—or even of a place of training—is no longer as clearly readable in the work. What once might have been described as regionalism was shaped by looking outward from one’s own studio toward the world, rather than by working within the studios, references, and images of others. Today, shared visual languages circulate quickly, and the material landscape of jewelry has become less geographically specific and more globally entangled.

Within this context, the act of placing jewelry in a museum carries particular weight. When a work is given space in a museum, that space suggests something has been earned—that a position has been negotiated, claimed, and recognized. Jewelry, without question, has entered what has long been considered a temple of art. Yet this recognition raises further questions: Where exactly is jewelry placed within the museum? What do the neighboring rooms focus on? What other narratives surround it?

An exhibition does not exist in isolation. Its meaning is shaped by proximity—by what comes before and after, by what hangs on adjacent walls, and by the disciplines it is placed alongside or apart from. In this sense, Constellations is not only an exhibition of objects, but also an experiment in positioning: jewelry situated within a broader institutional and cultural framework.

This inevitably leads to questions of audience. Who is the exhibition for? Which viewers does it imagine and welcome? Is its intention primarily educational, mapping a historical timeline for those already familiar with the field? Or does it function as a cultural artifact—a means through which the identity of a field can be read, questioned, and reinterpreted by a wider public?

An exhibition can be both archive and proposition. It can preserve histories while simultaneously opening new readings. Constellations operates within this duality, offering enough structure to orient the viewer while resisting a single, authoritative interpretation.

Here, the role of display becomes central. Pairing works, establishing categories, and defining an order are never neutral acts. The challenge lies in holding a careful balance: offering sufficient information to contextualize the work while preserving the distinct handwriting, voice, and agency of each maker. Too much explanation risks flattening difference; too little can obscure meaning. In Constellations, the installation navigates this tension with restraint, allowing relationships to emerge through visual and spatial dialogue rather than through didactic instruction.

The legitimization offered by the museum inevitably has consequences. It can attract new collectors, but also new spectators—viewers who may not come from within the field of jewelry at all. This shift in audience matters. It suggests a movement away from jewelry speaking primarily to itself, toward jewelry engaging a broader cultural conversation.

Constellations can be read as the end of an era in contemporary jewelry—the era of self-assertion, of material and political positioning as proof of existence. By bringing together works that span decades, the exhibition creates a necessary pause: a moment of collective reflection that allows one chapter to close without ceremony. From this pause, contemporary jewelry appears less as a movement in need of definition and more as a language prepared to begin again, grounded in awareness, complexity, and historical depth, and open to forms and questions that have not yet taken shape.

Note: Constellations: Contemporary Jewelry at the Dallas Museum of Art is accompanied by a catalog of the same name. It’s the first-ever publication dedicated to the DMA’s contemporary jewelry holdings. Authored by exhibition curator and the museum’s Margot B. Perot Senior Curator of Design and Decorative Art, Sarah Schleuning, the publication offers a series of richly illustrated thematic essays that delve into the nonlinear and nontraditional “constellations” at the core of the exhibition. The 456-page work also extensively frames the history of the museum’s contemporary jewelry holdings while serving as a meticulously detailed catalog depicting more than 900 works from the collection.

The opinions stated here do not necessarily express those of AJF.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here. The page on which we publish Letters to the Editor is here.

© 2026 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org