- This substantive, educational, and enjoyable exhibition celebrates an innovative maker renowned for his technical and aesthetic contributions to studio jewelry

- Curated by Rebecca Elliot, it issued from the Mint Museum’s acquisition of a large amount of Ebendorf’s jewelry from the collectors Ron Porter and Joe Price, as well as the Robert W. Ebendorf Archive

- The exhibition reveals the breadth and depth of Ebendorf’s artistic output and influence as an educator and mentor

Objects of Affection: Jewelry by Robert Ebendorf from the Porter • Price Collection

April 27, 2024–February 16, 2025

Mint Museum Randolph, Charlotte, NC, US

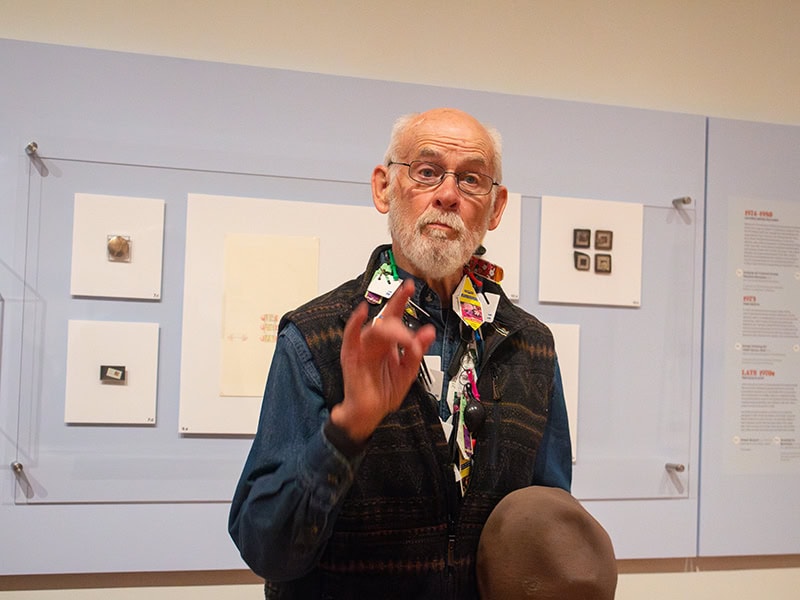

The legendary American artist Robert Ebendorf is renowned equally for his technical and aesthetic contributions to the field of studio jewelry. An innovative thinker with a passion for materials, he has mentored legions of American jewelry artists during a long and respected university teaching career that spanned 1964–2016.[1] Ebendorf has participated in countless exhibitions and had a notable traveling retrospective show in 2003–2004. Yet only the current exhibition, at the Mint Museum, in Charlotte, NC, has shown the breadth and depth of his artistic output and influence as a mentor.

The genesis of the exhibition, thoughtfully curated by Rebecca Elliot, lies in the Mint’s 2019 acquisition of an extraordinary trove of Ebendorf’s jewelry from the collectors Ron Porter and Joe Price—work mostly made while he was teaching at East Carolina University—as well as the Robert W. Ebendorf Archive. The exhibition is augmented by pieces from the Mint’s own previous holdings of Ebendorf’s jewelry, thereby demonstrating the full nature of the museum’s commitment to the artist. Given these close relationships, the show highlights interpersonal and institutional connections, drawing the visitor into Ebendorf’s private and professional worlds.

Over his 60-year career, Ebendorf has not adhered to one style or influence. On the contrary, his continued openness to exploring new ideas and pathways sets him apart from other jewelry artists of his generation. While there is no one defining aspect of an Ebendorf jewel, his approach consistently favors strong visual patterns and juxtapositions of color and texture. These characteristics are achieved through the use of diverse materials including precious metals, gemstones, alternative materials, found objects, and drawings. Many of the objects that Ebendorf creates have personal associations and meaning. Throughout the exhibition his wry sense of humor also comes through. All of these aspects of Ebendorf’s oeuvre are presented through pieces that encompass Scandinavian influences, pop culture, narrative imagery, and text elements, as well as themes ranging from religion to memory.

Objects of Affection is organized chronologically over two galleries. This is a smart choice. Given his diverse production, a thematic installation would be confusing and not nearly as illustrative. The first gallery covers the 1950s to 1990s. Casework design and placement, as well as framing wall colors, ensures that the jewelry is easily seen and can be examined at a close range. Large-scale photo murals picture the artist in his youth. They inject warmth and personality into the gallery, and provide an additional layer of information about the artist. Generous amounts of text accompany individual pieces as well as the decade-spanning sections.

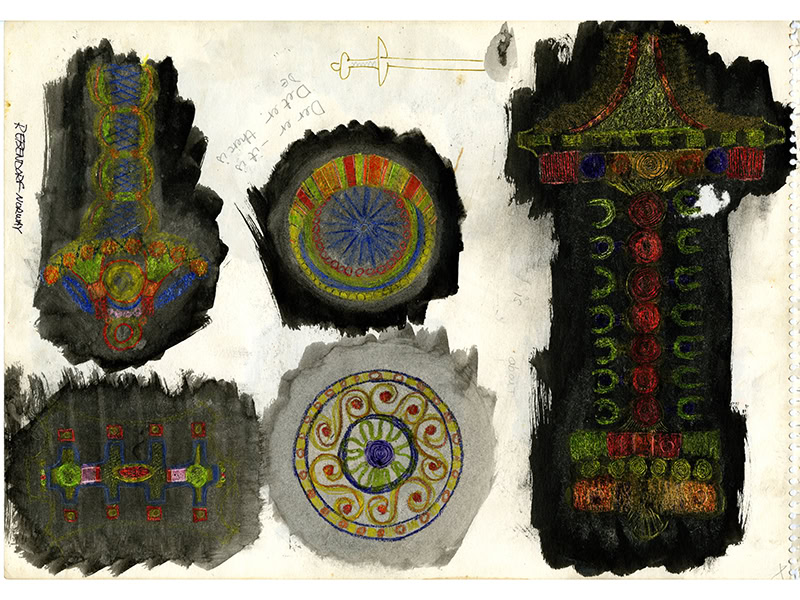

Visitors are first presented with the rare treat of a number of Ebendorf’s earliest works—jewelry and accessories that he made in high school and college in the 1950s and early 1960s. These pieces demonstrate his facility with metals and adherence to the reigning Scandinavian style of the time. His Fulbright Fellowship to Norway, in 1963–1964, and his Tiffany Foundation Grant, in 1966–1967, allowed him to study the Nordic style first-hand. The drawings included from this period offer insight into his design sense and use of color.

As the exhibition progresses, pieces representing significant bodies of work dating through the 1990s are displayed, often with accompanying drawings. The terrific drawings provide insight into another aspect of his practice and creative process. The selections make apparent that Ebendorf worked with alternative materials and mixed media to explore their potential for aesthetic juxtapositions rather than just for their ability to present specific narratives. However, narrative intent is sometimes present or alluded to through Ebendorf’s descriptive and often witty titles.

Of particular note in this section are rarely seen brooches from 1969 that include photographs. In their materials, construction, and aesthetic, they echo the type of jewelry the renowned American artist J. Fred Woell was concurrently creating. Ebendorf did not know Woell at that time, and felt alone in his style of making. He later recalled that when he met Woell at the Society of North American Goldsmiths’s inaugural conference, in 1970, he felt a sense of comradery—Woell was “hearing the same music that he [Bob] did.”[2]

plastic laminate, copper, 7 ¾ x ⅝ x ¼ inches (197 x 16 x 6 mm), Collection of

The Mint Museum, Gift of Porter • Price Collection, 2019.93.1, photo courtesy The Mint Museum

In the mid-1980s, many industrial manufacturers of new materials sent samples to artists for experiments. Others hosted competitions or solicited artist proposals for engagement with new products. In 1983, Ebendorf and his then wife, Ivy Ross, were invited by the Formica Corporation to experiment with its new ColorCore® material as part of the “Surface and Ornament” competition. While their brightly colored, geometrically patterned, and large-scale bracelets won a prize and were perfectly attuned to the aesthetics of the era, they are not as simple as they may visually seem. Ebendorf and Ross employed a mosaic technique using grout to create them, thereby including knowledge of historical jewelry and art-making in the designs.[3]

For those who have seen his jewelry before, the newspaper necklaces are often the most remembered forms. A Collar from 1988 stands out amongst the mixed-media work but gives way to the strong group of necklaces from the 1990s that comprise the final pieces in the first gallery. These represent a more spiritual side of the artist and include the touching Lost Soul, Found Spirits series. Made from found animal parts amongst other materials, these necklaces are elegiac and incredibly powerful.

Moving into the second gallery causes a shock to the senses. The clarity of the first gallery gives way to a more crowded installation. Here, Ebendorf’s jewelry from the 2000s–2020s, made during his time teaching in the East Carolina University Metal Design program (ECU), is examined in depth. Rather than clearly presenting the continuing arc of Ebendorf’s artistic explorations in direct context with the objects shown in the previous gallery, his more recent work is overtaken by the inclusion—though it is ultimately appreciated—of jewelry by Ebendorf’s colleagues and students. The emphasis on this era makes sense since Porter and Price began collecting his jewelry at this time, but this part of the exhibition suffers from trying to do too much in one space.

Nonetheless, there are some outstanding pieces in this section, especially those which reference the artist’s travel experiences. Other works find him returning to earlier themes of religion or incorporating materials such as animal body parts. While these newer jewels are the result of Ebendorf pushing himself forward and they brim with energy, color, and dynamic form, they do not possess the sense of discovery and quiet elegance of the older works.

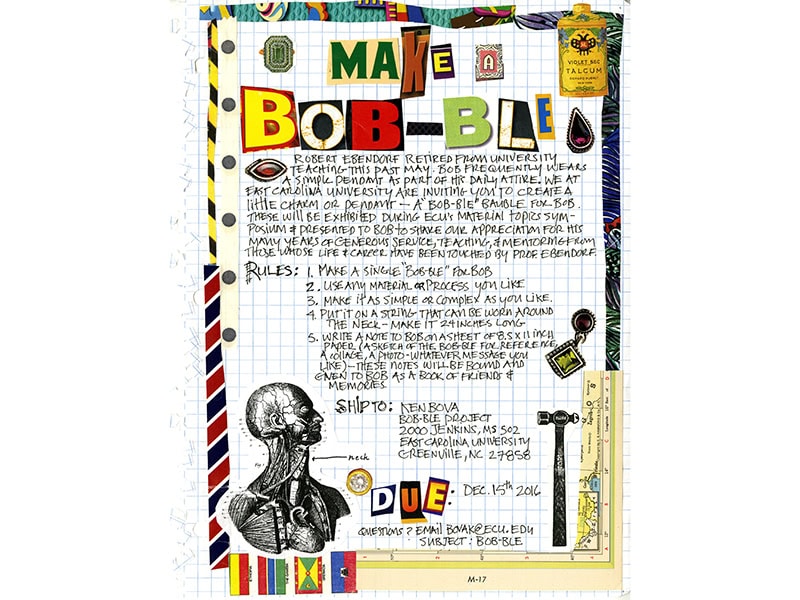

The collaborative pieces with former ECU students such as Zachery Lechtenberg are outstanding, and a welcome addition to the exhibition. Less so is the space given over to pieces from the “BOB-BLE” project, a call to ECU metals alumni, faculty, and students to make a simple pendant for Ebendorf on the occasion of his retirement. While the project demonstrates the ECU jewelry community’s strong feelings of love and gratitude, the pieces are uneven artistically. Including only one in the show, along with the album of the full project, would have sufficed. Ultimately, the jewelry by many of Ebendorf’s former students that is installed in two cases makes a stronger statement about the benefits of his teaching and mentorship.

The final gallery of the exhibition contains collaged postcards sent between Ebendorf and the collector Joe Price, as well as between the artist and Louis Bailey, the preschool-aged son of a colleague at East Carolina. These postcards are another important aspect of Ebendorf’s creativity. Only those lucky enough to be his friends or colleagues have the privilege of experiencing their richness and spirit. The display opens a revealing and thoroughly enjoyable window into a side of Ebendorf’s practice. This unexpected but very welcome addition to the exhibition clearly demonstrates the benefits of having access to an archive.

Objects of Affection is a substantive, educational, and enjoyable exhibition celebrating an important artist who has done so much for the field. The Mint is fortunate to have this treasure of a collection, and I can imagine many of the works finding their way into subsequent museum projects on jewelry or other aspects of art history. Therein lies the beauty of an Ebendorf jewel. Whether on its own or in a variety of contexts, it will always add to the dialogue between art forms.

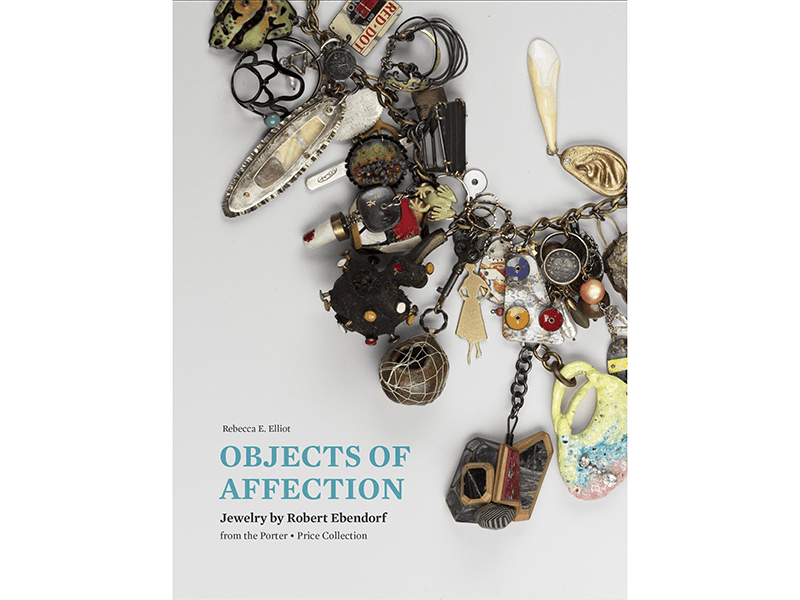

A richly illustrated catalog, with essays by Rebecca Elliot and Toni Greenbaum and interviews with the artist and collectors Ron Porter and Joe Price, accompanies the show. Visit the exhibition page here.

RELATED: Works from the Porter • Price Collection also serve as the base for another current exhibition, OUT of the Jewelry Box. Beryl Perron-Feller reviewed it here.

Reviews are the opinions of the author alone, and do not necessarily express those of AJF.

We welcome your comments on our publishing, and we will publish letters that engage with our articles in a thoughtful and polite manner. Please submit letters to the editor electronically; do so here.

© 2024 Art Jewelry Forum. All rights reserved. Content may not be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. For reprint permission, contact info (at) artjewelryforum (dot) org

[1] Ebendorf taught at Stetson University (1964–1966), the University of Georgia (1967–1971), the State University of New York, New Paltz (1971–1989), and East Carolina University, in Greenville, NC (1997–2016).

[2] Robert Ebendorf, interview with the author, November 13, 2018.

[3] Rebecca Elliot, exhibition wall text in Objects of Affection: Jewelry by Robert Ebendorf from the Porter • Price Collection, Mint Museum Randolph, 2024–2025.