After Wearing: A History of Gestures, Actions, and Jewelry

September 25–November 14, 2015

Pratt Manhattan Gallery, New York, New York, USA

Curated by Mònica Gaspar and Damian Skinner

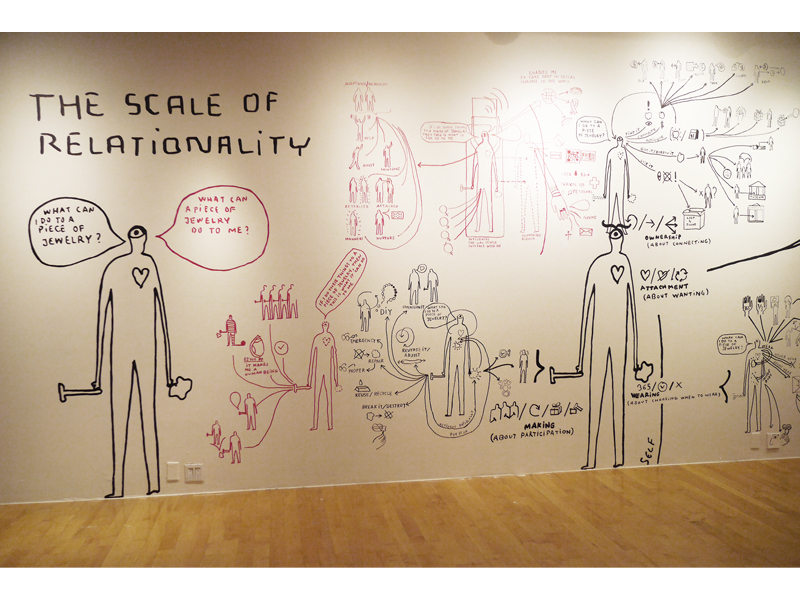

Visitors to After Wearing: A History of Gestures, Actions, and Jewelry, were greeted with an intriguing, if perplexing, display that included … no jewelry, at least in the traditional sense. Instead, show-goers encountered jewelry dematerialized into words and images that purported to expand the very definition of jewelry while examining how it inspires, per the catalogue essay, words, gestures, and actions through making, wearing, attachment, or ownership.[1] Helpfully, the curators—Gaspar, a design historian and researcher at the Institute of Theory at the Zurich University of Arts, and Skinner, an art historian and curator of Applied Art and Design at the Auckland War Memorial Museum Tamaki Paenga Hira, New Zealand—also provided a 47-foot wall installation called Scale of Relationality. It functioned as a kind of mind map to a conversation they had two years ago that evolved into this challenging, if at times opaque, show. In the catalogue, a recap of their dialogue reveals that their aim was to “relocate typical discussions about contemporary jewelry within a context of participation[2] and use through the format of an exhibition.”[3] They agreed that there was a need for research regarding “those jewelers whose work has become increasingly participatory, requiring action from, or interaction with, the audience in order to exist.”[4] This “wearer/owner/use” perspective, they felt, would be a valid basis for collaboration.

Gaspar, observing that “these projects seemed to belong to the kind of post-studio practices that had emerged since the 1970s,”[5] determined with Skinner that their approach should be post-studio as well, an insight that led them to “dump the jewelry”[6] and thus “activate the audience’s social imagination.”[7] Without this visual aid—created as a graffiti wall by Martí Guixé—the show may well have floundered, lacking a graphic thread connecting such diverse works as a wall of fake (non-realistic) beards; giant paper animal heads; ironically titled, closely cropped photographs of wealthy, but blemished, women wearing expensive conventional jewelry; video clips from Hollywood swashbucklers showing necklaces being torn off the necks of various heroines; a plywood sandwich board covered with 23-karat gold leaf; several flickering digital “brooches”; and a jeweler’s workbench minus the jeweler. Among these assorted installations, the most accessible was Mah Rana’s Meanings and Attachments (2002–present), photos of a global assortment of jewelry wearers paired with their comments on the nature of their emotional attachments to their pieces.

Some of these works, sorted into two sections—Gestures, and Participatory Projects—made their points effectively, but others were obscure in their relationship to the concept of jewelry and the show’s central aim. In a few instances, for example, the works on view seemed less concerned with elucidating the concept of jewelry—indirectly addressed via the disparate examples on view—than with the notion of “wearing” per se, or even more arcane issues. In the Gestures section, Joanne Wardrop’s Matrimonial Rituals, Gender Studies and False Facial Hair (2013) presented a fake-beard installation—items made of paper strips, tinsel, pompoms, straw, etc.—that was inspired by a four-day Angolan marriage ritual in which brides don straw beards and eyebrows and become “bridal boys” for a brief time at the end of the ceremony. This ritual was depicted in an accompanying video using stock footage[8] from the 1930s, and it was certainly fascinating to learn of an ethnographic example of transgender role reversal. Also featured in the video were a group of contemporary women wearing the wall beards and examining their responses to this affront/challenge to their gender. While interesting as an academic exercise in queer studies, this work’s relevance to jewelry remained obscure, especially as it lacked a curatorial statement. Instead, the viewer was left to wonder if the fun-fake beards on view are meant to be taken as jewelry simply because they are wearable.

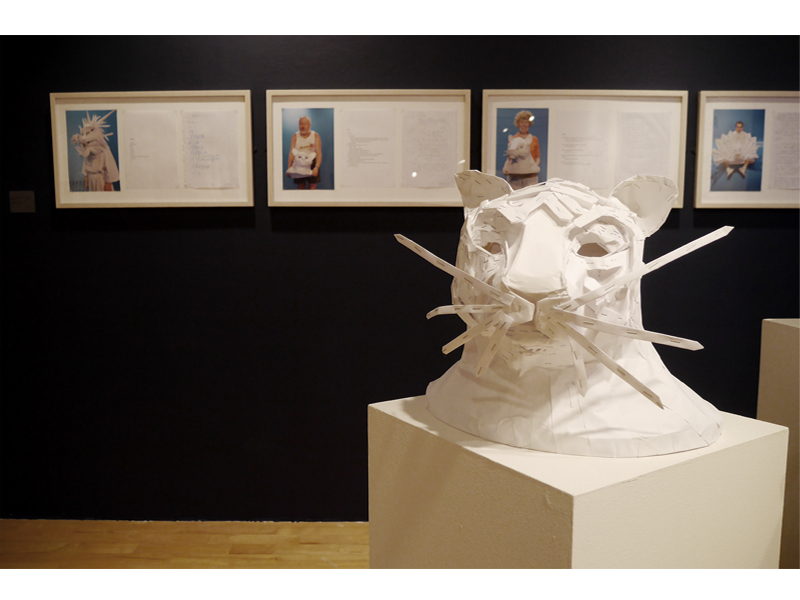

Likewise, Yuka Oyama’s enormous paper animal heads (mythical and otherwise; one 2010 dragon is titled Metamorphic Spirit), which in her words represented “expanded concepts of jewelry,” though delightful and a highlight of the show, provided less of a jewelry experience than an opportunity for highly theatrical cross-species transformation. Oyama is a trained jeweler whose website, tellingly, does not have a “jewelry” category and who is perhaps better known for her comically incisive performance art, e.g. actor/dancers costumed as cleaning utensils who perform karate katas. For this participatory work, Oyama had asked subjects to name their “inner animal,” then made the appropriate head and photographed the subject in question wearing it. These photos were displayed with the wearers’ comments about how it made them feel; “stronger, less shy,” stated a woman who donned a jaguar’s head.

Likewise, Yuka Oyama’s enormous paper animal heads (mythical and otherwise; one 2010 dragon is titled Metamorphic Spirit), which in her words represented “expanded concepts of jewelry,” though delightful and a highlight of the show, provided less of a jewelry experience than an opportunity for highly theatrical cross-species transformation. Oyama is a trained jeweler whose website, tellingly, does not have a “jewelry” category and who is perhaps better known for her comically incisive performance art, e.g. actor/dancers costumed as cleaning utensils who perform karate katas. For this participatory work, Oyama had asked subjects to name their “inner animal,” then made the appropriate head and photographed the subject in question wearing it. These photos were displayed with the wearers’ comments about how it made them feel; “stronger, less shy,” stated a woman who donned a jaguar’s head.

What’s being demonstrated here is an iteration of primitive rituals that seek empowerment through the wearing of constructed animal heads or real parts, such as claws, bones, and skins. But if you accept, as the artist maintains, that giant paper heads expand the concept of jewelry—yes, the glinting staples added a clue to jewelry—then (and you will ask in vain) why shouldn’t hats, or shoes, or handbags? Or what about cigarette packs held in the hands behind the back, as in the Dutch jeweler Robert Smit’s 1975 installation of 50 Polaroids of himself so posed, which he called Everyday Adornments? This series, meticulously reproduced in the show’s Gestures section with the original Polaroids held in place with silver pushpins, has been consecrated as the first instance of conceptual jewelry, an action that Smit performed (and photographed) to illustrate his radical contention that “any object could be jewellery if it was put forward as such.”[9] A related photograph, My Shadow Wears: Green Ticket (Barcelona), was from Roseanne Bartley’s 2012 series in which she took pictures of her own shadow positioned over various pieces of street litter. In the one on view, a green paper ticket functioned as a virtual brooch. On her website, Bartley states: “The performance My Shadow Wears was created over a four-day visit to Barcelona and suggests a symbiotic relationship between body, object and the environment (images taken on an iPhone).” Wall text in the exhibition suggested that anyone can do likewise, including casting a shadow on one’s own body—the hand or wrist, say—and snapping the picture.

Such an ephemeral action invites anyone to create and wear jewelry—no craft or money needed—a participatory concept Bartley takes further with her second project included in this show, Seeding the Cloud: A Walking Work in Progress. One of her colorful necklaces, made from pieces of found plastic (acquired on a walk) artfully inlaid with fake pearls, was displayed along with her DIY instructions (a take-away sheet that could be folded into a booklet). It addressed Bartley’s interests in “interpersonal jewelry experiences” and her focus on “the intersection between material culture and conceptual practice.”[10] This invitational aspect of jewelry and craft was also addressed via Gabriel Craig’s Pro Bono Jeweler video of himself, shown on an iPad located at the show’s unoccupied jeweler’s bench. Craig is known for taking his workbench and tools to the streets with the aim of engaging the public in the “magic” of jewelry making. He is a passionate proselytizer for jewelry, and craft in general, a person who literally stands on a soapbox in public spaces cheerfully haranguing—um, inviting—passersby to engage in a dialogue on his chosen field. As the Pro Bono Jeweler, he has been known to give away made-on-the-spot silver rings to anyone who stops and becomes involved with his activity. Show-goers who stopped to sit and view the video may not have been able to divine the full extent of Craig’s commitment. However, one has to be grateful for the fact that a reference to traditional craft was included in this mostly documentary show.

Related to that point, also in the Participating Projects section, was a photo presentation of Hochsitz (2010), a small room for jewelry practices located in a verdant meadow in northern Germany. Designed by Martí Guixé and built by company Makra Bau, the little building was created by Schmuck2 (no relation to the annual jewelry fair), a nonprofit “interdisciplinary platform,”[11] run by the German jewelry artist Susan Pietzsch, which seeks to help emerging artists on various levels—exhibitions, workshops, and more. The Hochsitz (or high house) is raised on stilts in the manner of hunters’ structures and features several windows and a transparent roof. Jewelers may apply to work there amidst the tranquility and natural beauty of the setting. What After Wearing did not include were pictures of jewelry created in the Hochsitz—nor could I find any evidence of such online—but a Facebook posting by the Japanese jeweler Naoko Ogawa showed the interior of the tiny house with her drawings laid out on a table.

This led me to another website in which Pietzsch wrote that Ogawa’s project would pursue “likenesses of jewelry that exist only momentarily through the diffusion and fragmentation of light.”[12] Of course! Jewelry is everywhere, and nowhere, as ephemeral as a ray of light or as invisible as a virus, which turned out to be the inspiration for this show’s only other project (along with Bartley’s necklace) that could be considered, with reservations, to be real jewelry: Lauren Kalman (where was her 2009 Tongue Gilding video?) and Kipp Bradford’s Virus Simulation (2011–2015) project—25 phenomenally complex brooches made of custom-designed circuit board electronics. While only a few of the brooches were presented, albeit secured within a clear acrylic box, their flickering lights drew intrigued viewers no doubt grateful to see something possibly wearable. But would the toxic symbolism of these visually alluring brooches attract or repel jewelry wearers? The wall caption described the concept for these interactive electronic brooches that mimic the spread of the human papillomavirus (HPV). The flickering lights are programmed to interact with each other, just as real viruses spread from one person to another. Viewers may or may not understand that HPV is a common vector of sexually transmitted disease and a potential cause of cervical cancer, information omitted from the caption—as was the fascinating fact that the brooch designs are based on microphotographs of actual viruses.

This led me to another website in which Pietzsch wrote that Ogawa’s project would pursue “likenesses of jewelry that exist only momentarily through the diffusion and fragmentation of light.”[12] Of course! Jewelry is everywhere, and nowhere, as ephemeral as a ray of light or as invisible as a virus, which turned out to be the inspiration for this show’s only other project (along with Bartley’s necklace) that could be considered, with reservations, to be real jewelry: Lauren Kalman (where was her 2009 Tongue Gilding video?) and Kipp Bradford’s Virus Simulation (2011–2015) project—25 phenomenally complex brooches made of custom-designed circuit board electronics. While only a few of the brooches were presented, albeit secured within a clear acrylic box, their flickering lights drew intrigued viewers no doubt grateful to see something possibly wearable. But would the toxic symbolism of these visually alluring brooches attract or repel jewelry wearers? The wall caption described the concept for these interactive electronic brooches that mimic the spread of the human papillomavirus (HPV). The flickering lights are programmed to interact with each other, just as real viruses spread from one person to another. Viewers may or may not understand that HPV is a common vector of sexually transmitted disease and a potential cause of cervical cancer, information omitted from the caption—as was the fascinating fact that the brooch designs are based on microphotographs of actual viruses.

Gaspar told me that these viral brooches—essentially biotech jewelry expressive of the many pathogenic threats we unknowingly live (and die) with—could be tried on if the viewer asked permission, a fact not stated on the caption. This omission, perhaps intentional, highlighted the show’s main weakness. Richer printed information and some curatorial wall texts could have supplied puzzled viewers with expanded “relationality” rationales for the inclusion of specific projects—the dubious fake beards, for example, or the photo of Jhana Millers wearing a gilded sandwich board, a crude advertising apparatus enlisted to convey a conceptual absurdity in that real gold is expended for the sake of negating its value.[13] This familiar art-jewelry-world trope—the denigration of the use of precious materials for their own sake—is reinforced by Jessica Craig-Martin’s brutally ironic, closely cropped photos of celebrity women at play, their expensive jewelry serving as emblems of shallowness and wretched excess. Here were two stylistically divergent yet on-message images with negative connotations that begged for a curatorial point of view. Were Skinner and Gaspar stating a policy position re commercialism, or simply staking out extremes of wearing?

Left to themselves, show-goers may have found aspects of the exhibition provocative, yes, but also off-putting. The problem was that they were there mainly as passive viewers of the projects, many of which required further explication to be fully understood and/or evaluated—hence my extensive Googling. And there was something counterintuitive about presenting participatory art in what amounted to a textbook setting. Had After Wearing been presented entirely online as an interactive work of art in itself, the show might have gained in effectiveness. I mean, once you dump the jewelry, why not dump the venue as well? Here was a show that assumed a “post-studio” posture only to embrace the gallery. By relocating post-gallery, i.e. online, After Wearing would have opened its virtual doors to a far greater audience invited to share its responses to the show’s unstated yet strongly implied question: What exactly is contemporary “jewelry,” and does relocating “typical discussion” of it “within a context of participation and use”[14] in fact advance the case for a wider appreciation of this richly creative though long marginalized field?

Left to themselves, show-goers may have found aspects of the exhibition provocative, yes, but also off-putting. The problem was that they were there mainly as passive viewers of the projects, many of which required further explication to be fully understood and/or evaluated—hence my extensive Googling. And there was something counterintuitive about presenting participatory art in what amounted to a textbook setting. Had After Wearing been presented entirely online as an interactive work of art in itself, the show might have gained in effectiveness. I mean, once you dump the jewelry, why not dump the venue as well? Here was a show that assumed a “post-studio” posture only to embrace the gallery. By relocating post-gallery, i.e. online, After Wearing would have opened its virtual doors to a far greater audience invited to share its responses to the show’s unstated yet strongly implied question: What exactly is contemporary “jewelry,” and does relocating “typical discussion” of it “within a context of participation and use”[14] in fact advance the case for a wider appreciation of this richly creative though long marginalized field?

[1] After Wearing: A History of Gestures, Actions, and Jewelry. Curated by Damian Skinner and Monica Gaspar. September 25–November 14, 2015. Pratt Manhattan Gallery, New York, 6–7.

[2] See http://jaumeferrete.net/text/Bishop-Claire-Artificial-Hells-Participatory-Art-and-Politics-Spectatorship.pdf.

[3] Skinner/Gaspar, 2.