Ebony G. Patterson: … buried again to carry on growing …

The Museum of Arts and Design, New York, New York, USA

November 10, 2015–April 3, 2016

You know the space well—it’s one of the only permanent fixtures in the Museum of Arts and Design (MAD) in New York City. The gallery is funded by the Tiffany & Co. Foundation and opened with the museum’s move in 2008 as the first gallery in the United States dedicated solely to the exhibition of contemporary jewelry. The space is built with two large display cases. One is long and linear, with drawers for storage of the permanent collection, and the other is a freestanding oval-shaped structure with an open interior situated in the middle of the room.

The vitrine, necessary for the security and conservation of precious metals and gemstones, has often been discussed as a barrier for viewers to engage with the artwork.[1] The Plexiglas meant to protect and even elevate the work on display becomes a physical reminder of a functional object’s stagnant entombment within. This tension is underlined in the example of the Tiffany Gallery at MAD, where the display cases are designed in such a way as to draw attention to themselves. No matter what exhibition is on view, often the first thing I notice when entering the space is the bulky, elliptical case in the center of the room—like a sci-fi aquarium filled with art.

Permanent fixtures, such as the ones at MAD, have to be taken into consideration with each new installation. A curator would be aware of the tension between the visual prominence of the display case compared to the scale of what is on display. Further, these conspicuous structures must be contemplated in terms of their effect on returning visitors as well as exhibition design and layout. The prominence and permanence of the cases runs the risk of making the space feel unchanging. And yet such areas in a museum propose both a constraint and an opportunity.

I Spy Something … Canonical

Recently, artist Ebony Patterson was invited to stage an intervention in these display capsules in conjunction with her traveling exhibition Dead Treez. Patterson’s mediation is the first in a new POV, or Point-of-View, series at MAD where artists are invited to curate the museum’s permanent collection. Patterson’s installation provides a fertile ground for discussion, both in its content and construction. However, in this article I have only chosen to address a few aspects of this work, centering on the role of the artist-as-curator and its impact on the interpretation of permanent collections.

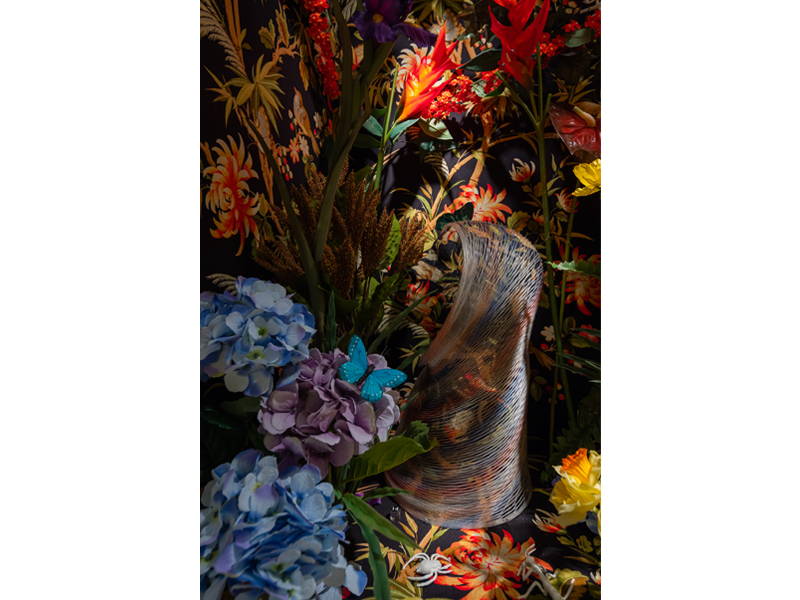

Entering the Tiffany Gallery for Patterson’s exhibition, titled … buried again to carry on growing …, you pull aside a dark, heavy curtain—the first indicator that something here is different. Inside, the cases pulsate with color and light in an otherwise dark environment. A vibrant array of flowers fills the containers. The overall effect is reminiscent of a reptile house at your regional zoo. I half expected to see condensation from the tropical environment gathering on the glass. But this is not the zoo, and a second look at the exotic plants reveals they are unabashedly fake. Hydrangeas mingle with birds of paradise, red ginger, daffodils, and poppies. Synthetic butterflies perch on top of petals, and plastic insects scurry in the pretend ecosystem.

As you look closer, mannequins adorned with bright, floral patterns emerge from the flora and fauna. They are not staged in vogue-like poses for commercial consumption, but rather positioned so that the forms lie on the floor of the display case, limbs splayed out as if found in a crime scene. Fake bodies lost in a fake wilderness. And on the figures’ wrists, around their necklines, decorating their waists, and scattered thereabouts is the museum’s permanent collection of contemporary jewelry: gold watches, brass knuckles, large crosses, glittering belts, gaudy rings, and all.

The terrarium-like displays layered with bright colors and patterns invite visitors into a game of “I spy.” The eye traverses the landscape and is rewarded when it distinguishes a work of art from the ornamental background. Patterson’s display strategy encourages viewers to slow down and look closely. Through the visual satisfactions of seeking and finding, you get to experience the excitement of discovery often lost in stationary museum displays where the viewer is told what to see and in what order.

The success of this display strategy is in part dependent on the use of the Plexi cases. Patterson is not trying to make the viewer forget they are there. Instead, she is able to mitigate the barrier-like quality of the vitrines by drawing attention to them. She uses the language of dioramas and habitat displays, which attempt to capture an environment within a confined space.

Playing Patterson’s game of hide-and-seek, an informed eye might recognize Caroline Broadhead’s Veil Collar (1983), the circular monofilament draped over the elegant neck and head of a floral figure. Or maybe we spy Bruno Martinazzi’s Metamorfosi (1992), or Joyce J. Scott’s Lovers (2002), or Wendy Ramshaw’s set of six ring stands and rings (1981) nestled among the flowers. But for visitors without a working knowledge of major creations in the cannon of contemporary jewelry, these sorts of discoveries may be lost altogether. And while an exhibition checklist is made available for the historically curious, the artist, maker, materials, date, or significance of these works does not seem to be the point here. The visual narrative is not about tracing artistic movements throughout history—it is about realizing Patterson’s artistic vision. We might ask ourselves what is lost and what is gained when artists, given the use of the permanent collection, use museum objects in their work?

The Artist-as-Curator: Contemporary Practice or Visitor Attraction?

The concept of artist-as-curator is not a new strategy, and the stakes of such interventions have been discussed at length.[2] Notably, most examples of the artist-as-curator seem to focus on animating collections of craft and decorative arts. For example, Fred Wilson’s 1992 exhibition, Mining the Museum, at the Maryland Historical Society, Pedro Lasch’s 2007 Black Mirror/Espejo Negro at the Nasher Museum of Art, Grayson Perry’s 2011 The Tomb of the Unknown Craftsman at the British Museum, or Valerie Hegarty’s 2013 intervention in the Brooklyn Museum’s period rooms. For these artists, the permanent collection offers a means to critique the work of the museum, such as institutional collecting policies and the (often) dominant cultural narratives that drive these decisions. Wilson used the Maryland Historical Society objects to retell the history of slavery, for example, and Hegarty took advantage of the Brooklyn Museum’s period rooms to address the subject of colonialism. Projects such as these give artists access to objects and environments already charged with cultural and historical significance.

But there is the question of why working with permanent collections is interesting to the artist, and there is the one of why having an artist work with a permanent collection is interesting to the curator/institution. Like the well-known example of the frame that points to something lacking in the painting, these interventions, reinterpretations, and installations highlight the inherent challenge of showing functional objects—or even worse, historical functional objects—in a museum setting. The artist-as-curator offers a way to enliven, to activate, such otherwise overlooked spaces. Let’s take, for example, Hegerty’s intervention in the dining room of the Brooklyn Museum’s Cane Acres Plantation. Here the artist staged a 19th-century still life under attack by a band of raucous black crows, wings frozen in a state of mad flapping as they strike, Hitchcock-style, at the bursting fruit dripping off lavish platters. An institutional critique from the perspective of contemporary art, Hegarty’s intervention is also a way to draw audiences to a part of the museum that, I would venture, gets less traffic than the painting wing. The drama, surprise, and concept of the scene offers a visual and intellectual reward to visitors who seek out this installation on a level that a well-written label just cannot.

One of These Things Is Not Like the Others

Compared with such artist-as-curator predecessors, Patterson’s installation takes a different strategy to using the permanent collection. Whereas the interventions by Wilson, Lasch, Perry, and Hegarty were focused on using the objects in the museum’s collection to draw attention to alternative historical readings or reassert underrepresented historical narratives in an act of institutional critique, Patterson’s intervention does neither. Instead she uses the permanent collection to construct and convey her own point of view, to the extent that the history and context of production of the objects selected for display seems beside the point.

The exhibition’s title, … buried again to carry on growing …, and the wall text both work to draw out the metaphor constructed between gardens, adornment, and marginalized communities. The title is a reference to the poem Brief Lives, by the Jamaican author Olive Senior, which recounts how death comes early to members of the narrator’s community, often due to drugs or political conflict. The wall text extrapolates: “choices in clothing, jewelry, or other forms of personal adornment are endeavors to be visible on the part of populations rendered invisible by poverty, racism, and other oppressive socioeconomic conditions.” In Patterson’s garden, jewelry turns up like clues to a crime, both the staged murders presented in each display case, but also the greater social crimes of systematic racism and institutionalized poverty. Jewelry, Patterson’s exhibition argues, can operate as communicator of social injustice.

Like the vivid plants on display, the objects selected from the permanent collection are ostentatious in their scale, materials, and process, and they reference ideas of violence and luxury. There are brass knuckles, gaudy chains, and jewel-encrusted pendants. The symbolic reading of the works—their visual references to images prevalent in popular culture—is privileged over the work’s original intention or context of production. Broadhead’s Veil Collar, for example, was presumably not chosen as an exemplar of the skillful and radical use of nontraditional materials or the way the monofilament was constructed to sit on the body, but rather for the secretive or unsettling implications of mourning that a veil might elicit in the viewer.

A New Life for Dead Collections?

Thus the museum objects in … buried again to carry on growing … have two conflicting and simultaneous roles to play. On the one hand the works function in the realm of a permanent collection, representing objects of historical significance and development within the field of jewelry. On the other hand, the viewer is being asked to see past or ignore the historical significance of the objects, and approach the works as symbols representing the ideas and values of jewelry more broadly. Patterson’s intervention is both an exhibit of MAD’s collection and an exhibition; and amidst this dual role, tensions arise.

For instance, 99% of MAD’s permanent collection is not representative of what oppressed communities are wearing. These are objets d’art, collected by a social elite, and therefore particularly inept at evoking the sartorial resilience of the oppressed. Like the selection of poisonous flowers chosen for the installation, meant to allure only to cause damage, the reality of the jewelry’s production and consumption is toxic, so to speak, to Patterson’s no less important vision.

While Patterson’s intervention neglects the historical significance of the particular works of jewelry, her installation uses the vitrines to reactivate the objects within their entombment through staging an elaborate game of hide-and-seek, breathing cultural relevance back into their display. Thus the artist-as-curator may continue to be an important strategy in museum interpretation, particularly for craft and decorative arts. In this light, Patterson’s title … buried again to carry on growing … could also be read as a sort of epitaph for the many objects “buried” and “resurrected” in museum collections through artist-as-curator interventions.

INDEX IMAGE: Installation detail of … buried again to carry on growing … A POV by Ebony G. Patterson at the Museum of Arts and Design, work in foreground: Merry Renk, “White Cloud” Wedding Crown, 1968, photo: Butcher Walsh © Museum of Arts and Design