The world of objects is also a place for desire. The way we relate to different materials, and corporeal realities, as well as the social, cultural, and emotional relationships that we experience as we use different objects or when we appreciate the value of their design, are the models according to which we shape our subjectivity, identity, and sense of belonging in the contemporary world.

Contrary to other sumptuary objects that belong to the extensive world of luxury, contemporary jewelry shares a common denominator with works of art: its value is not only in the signature it carries, its materiality or manufacturing process, but in its symbolic load and in the meaning it carries. One of the main characteristics of these objects is excess. The symposium En Construcción II was a unique opportunity in this region to support critical thinking about the surplus that characterizes the objects that are currently produced by jewelers, and also the role they play in contemporary culture.

The event featured five Latin American exhibitions and one special curatorship program that incorporated the works of four European artists (Lisa Walker, Celio Braga, Gemma Draper, and Manuel Vilhena), who were also invited to lead four workshops and an open-access symposium where their creative perspectives were presented. The symposium took place in Centro Cultural de Valparaíso—a former prison refurbished as a cultural center that was home to many political prisoners during the dictatorship in Chile and doubled as a torture center—and it brought together more than 60 artists, designers, and jewelers from Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Venezuela, Ecuador, Colombia, Uruguay and Chile. The project was conceived —and implemented over the last year— by Pamela de la Fuente, director of the Escuela de Joyería, Santiago, Chile and by Francisca Kweitel, from Argentina.

The name of the symposium, En Construcción II, seems to be appropriate when thinking about contemporary jewelry in a global context where information spreads rapidly and where boundaries seem to expand very quickly, to the point of chucking overboard questions on the specific nature of this practice (if it exists) and its discourses. How do we understand contemporary jewelry in Latin America? I think that it is not enough to make reference to contemporaneity just for the sake of presenting objects that were designed and produced in the present. Moreover, local identity can not be defined through the works or by the national border in which they are produced. Thinking about the distinctive features of these objects implies going beyond territory and abandoning the deceitful determinisms of regionalism.

Here and Now

This symposium highlighted the place that our present time occupies in the creators’ imagination as well as all the rhetoric that it allows. Additionally, it proposed a reflection on the politics of the object, that is, thinking about objects’ role in the construction of the subjective experience in our time and space. A good example is the Mexican exhibition titled Lo Inesperado de lo Cotidiano (What’s Unexpected in Domesticity). From an anthropological perspective this exhibition proposes a reflection on creation and its motivations, positioning the local social context as a matrix.

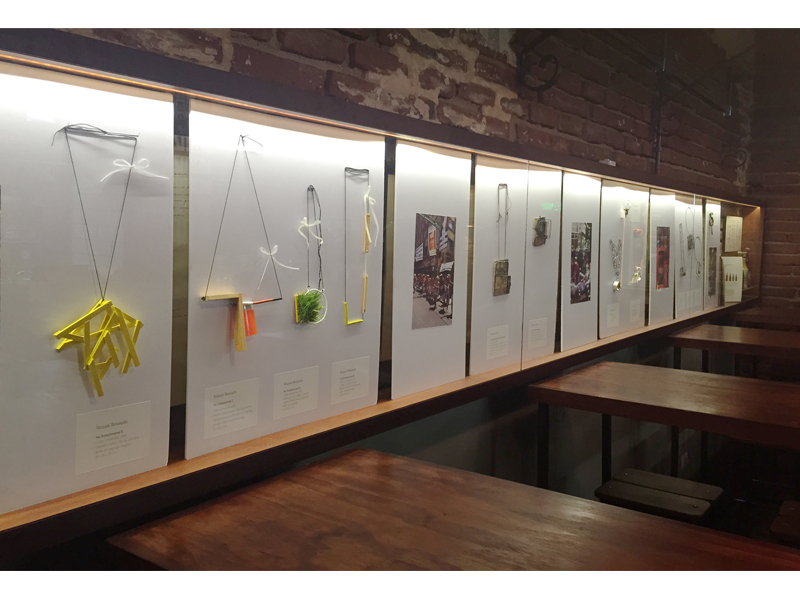

The jewels portray this relationship quoting the urgency and survival practices of anyone traveling across large Latin American cities under the stigma of precariousness. The jewels that are exhibited at the entrance of “la cervecería” are made of residual materials that have been ditched from the industry of urban transportation. The reference to these jewels is the mobile architectures in street markets that are common in Mexico City and in different Latin American cities, such as Valparaíso. Made of tires, bicycle chains, ropes, and wires, these jewels highlight the value of the design and engineering that is usually lacking in more formal jewelry settings. On the other hand, some objects have been elaborated with industrial materials, using the techniques of weaving and knitting learned from the local tradition, from textiles and handicraft basket-making. Consequently, the heritage of handicraft and popular practices are preserved, while also promoting recycling, a relevant practice in one of the most polluted cities in the world.

If the representational and symbolic dimension of culture has been a place of conflict and debate between center and periphery, tradition and innovation, local and universal, we then need to think which political relations can be established between the two apparently distant contexts of Europe and Latin America. Intersections, dialogues, and resistances: in my opinion, contemporary jewelry constitutes a fruitful ground in local forms of representation of power, where image and identity critically intersect at the boundaries of art and design, work and technology, exclusiveness and mass production. From this perspective, contemporary jewelry straddling these territories inherits the history of their hybrid identities: of a form of capitalism lacking cutting-edge technology and of an economy with scarce local factories.

It is about thinking about the extensions of a practice that proposes to go beyond techniques and work procedures. Contemporary jewelry occupies a space in between, in which sculpture is in tension with objects, where the body participates—being hidden or exposed. This boundary space is where objects circulate in the edge between user and collector, fashion and style, gallery and curator on the one hand, and market and public eye on the other.

Dismantling Luxury

If contemporary jewelry has offered a space for critical thinking today, it is because it has challenged the traditional representation of power when dismantling the formal categories and materials that signify and determine luxury. This is jewelry with an extended material palette, incorporating traditional, scarce, durable, or expensive materials, those that are abundant, that are ephemeral and cheap. An example of that would be the work produced in Lisa Walker’s workshop. She proposed a reflection on the circulation, manipulation, use, and re-signification of ordinary objects. Far from the material tradition of luxury, these new products and their redefinitions revealed, from a critical perspective, the obsolescence and excessive proliferation of products and images of the neoliberal market. The Argentinian exhibition Muestra, Subconjunto de Casos de una Población Estadística Argentina, in my opinion, seemed to follow a similar experimental path as Walker’s workshop. It was held in a clothing store named Mercado Moderno and it was curated by Lucía Brischina and Francisca Kweitel, who also worked to organize the symposium. The exhibit used the infrastructure of the store and its windows to affix different objects on its own foundation (a white shirt). On the one hand, the use of this pattern allowed the viewer to see differences and properties in each jewel. And on the other it restricted intervention to the front of the torso. Just like its title indicated, this exhibition, unlike all the others, did not gather under one concept the objects that it exhibited. That non-curatorial decision can be interpreted as resistance to the standardization of Argentinean production or as a representation of the very modern market that offers mass use of what’s new, or as a parody of the homogenization of the differences in the global world. From this latter perspective, the jewels could be seen as a series of samples from a much wider corpus of creations, among which I can highlight textile projects made with felt, crochet weaving, miniature embroidery, small minimalist sculptures made with recovered wood, spinning dyed balls, and leather weaving.

Politicizing the Body

Contemporary jewelry has also politicized the body that carries it. In some cases invading the decorative and ergonometric properties of design has triggered this. I’m talking about objects that affect the position of the body and imbue it with meaning, while they re-signify it symbolically and aesthetically. Sometimes these objects evoke the body. At other times they modify it, fragment it, unify it, and, like prostheses, they sometimes hold it, transform it, or antagonize it. In this line, the work done by Celio Braga in the workshop, exhibition, and seminar put on stage the relations between body and memory. From the deconstruction of old garments and thoughts about the significance process of materials, Braga proposed the reconstruction of new objects that would emphasize their emotional dimension. This perspective was embodied by some objects displayed in Rizomas y Objetos Fluídos, an exhibition held in Valparaíso’s Lutheran Church, which is part of the architectural heritage of the city. The exhibition gathered the work of young creators from the Pamela de la Fuente Jewelry School, one of the organizers of the conference. The main focus of this exhibition was to propose a reflection on how we depict objects today and how we relate with them when their function is mainly symbolic. Notions such as angst, aging, death, and mourning were the underlying notions of those jewels.

RE-TRATO was an exhibition held by the Brazilian group Broca in an art gallery located inside a bookstore in one of the most popular tourist hills of Valparaíso. It presented a series of works designed to represent corporal trauma. Each piece talked about a zone in every body that had been damaged—and simultaneously incorporated an iconography of pain and absence. In my opinion, the exhibits that were shown were able to materialize by formally incorporating the artistic tradition of Brazilian neoconstructivism and the long-standing tradition of etching and textile, as well as to refer to the performative practices of Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica, and Lygia Pape.

Broca was formed as a study group in the year 2012, from the first symposium En Construcción that took place in Argentina. From its inception, its 12 members have developed research and experimentation that have revolved around processes and languages in contemporary jewelry. The exhibit at that time constituted the first collective project and in it they posited the body as the central axis of creative experience. Using their own backgrounds as a starting point, they elaborated pieces that in some cases, in a very literal way, alluded to traumatic experiences that were both physical and subjective. This project’s perspective on gender was open—and less targeted, certainly, than the exhibition that followed.

Erótica was held by a group of jewelers from the Chilean Association of Contemporary Jewelry in a gallery located next to one of the traditional funiculars that are commonplace in Valparaíso. It addressed existing stereotypes in gender and sexuality by appropriating the display strategies that exist in the jewelry market: body, object, image, and display platform worked together to evoke, and play with, the current norm for the body. Ranging from metal prostheses and textiles to molds of body parts, the majority of the objects represented erogenous and genital zones. Many of these objects evoked the shape of the body, and the senses. Some, I think, could be seen as dildos and others as torture artifacts.

Conclusion

Lo Inesperado de lo Cotidiano, the Mexican exhibition discussed at the beginning of this essay, showed, from an anthropological perspective, the relations between object and context. It was a political proposal in the sense that it made a connection between collective imagination and everyday, urban experience, by citing the needs and survival practices of those who live under the stigma of precariousness in South America’s biggest cities. Like a number of other projects on the program, it navigated the space that separates subjective experience from the collective, and what that means in a South American socio-economic context.

Jewelry lends itself particularly well to navigating that space, and to zooming in and out of individual experience in order to describe the construction of subjectivity. I found that focus of En Construccion II particularly interesting—and relevant to post-dictatorial cultures.

This initiative made manifest the lack of existing platforms for dialogue, discussion, circulation, and critical thought about the prolific and rich production of contemporary jewelry in Latin America. The efforts that were needed in terms of organization, management, financing, and broadcasting exposed the difficulties that must be dodged to generate these types of encounters, and establish critical dialogue within the South American region. Despite these adverse odds, this symposium was able to offer a place for deliberation and exchange in order to promote the dialogue between jewelers, artists, jewelry lovers, critics, spectators, and consumers. It was a success, which I hope will consolidate the presence and circulation of this cultural field in Latin America.